Thursday, April 06, 2017

Monday, June 03, 2013

|

| German Communist Party Poster |

Sunday, March 25, 2012

|

| Ethiopia |

Monday, October 24, 2011

Monday, January 24, 2011

As for myself, I broke down completely when the old gentleman tried to resume his story by informing us that we must now end this long war, because the war was lost, he said, and we were at the mercy of the victor. The Fatherland would have to bear heavy burdens in the future. We were to accept the terms of the Armistice and trust to the magnanimity of our former enemies. It was impossible for me to stay and listen any longer. Darkness surrounded me as I staggered and stumbled back to my ward and buried my aching head between the blankets and pillow.

I had not cried since the day that I stood beside my mother's grave. Whenever Fate dealt cruelly with me in my young days the spirit of determination within me grew stronger and stronger. During all those long years of war, when Death claimed many a true friend and comrade from our ranks, to me it would have appeared sinful to have uttered a word of complaint. Did they not die for Germany? And, finally, almost in the last few days of that titanic struggle, when the waves of poison gas enveloped me and began to penetrate my eyes, the thought of becoming permanently blind unnerved me; but the voice of conscience cried out immediately: Poor miserable fellow, will you start howling when there are thousands of others whose lot is a hundred times worse than yours? And so I accepted my misfortune in silence, realizing that this was the only thing to be done and that personal suffering was nothing when compared with the misfortune of one's country.

…

What a gang of despicable and depraved criminals!

The more I tried then to glean some definite information of the terrible events that had happened the more my head became afire with rage and shame. What was all the pain I suffered in my eyes compared with this tragedy?

The following days were terrible to bear, and the nights still worse. To depend on the mercy of the enemy was a precept which only fools or criminal liars could recommend. During those nights my hatred increased--hatred for the originators of this dastardly crime.

During the following days my own fate became clear to me. I was forced now to scoff at the thought of my personal future, which hitherto had been the cause of so much worry to me. Was it not ludicrous to think of building up anything on such a foundation? Finally, it also became clear to me that it was the inevitable that had happened, something which I had feared for a long time, though I really did not have the heart to believe it.

Emperor William II was the first German Emperor to offer the hand of friendship to the Marxist leaders, not suspecting that they were scoundrels without any sense of honour. While they held the imperial hand in theirs, the other hand was already feeling for the dagger.

There is no such thing as coming to an understanding with the Jews. It must be the hard-and-fast 'Either-Or.'

For my part I then decided that I would take up political work.2

Wednesday, April 28, 2010

The alleged stopping of Euthanasia in Germany in 1941

At the beginning of the movie The Mad Women of Chaillot (1969) there is brief written prologue that goes:

This is story about Good Triumphing over Evil. Of course it is a fantasy.1

In this posting I am examining another fantasy of Good triumphing over Evil. In this case it is an historical fantasy of the triumph of Good over Evil, and like most such fantasies it is not altogether false but is distorted and conceals more than it reveals.

It is also a fantasy that helps people feel good and downplays just how really difficult it is to do good and by neglecting the failure, or more accurately turning failure into success it lies. However it does serve the purpose of helping to hide a shameful series of moral failures and in making people feel good about themselves and how supposedly easy it is to do good in difficult circumstances.

The example I’m giving is the Hitler’s order to stop the Euthanasia campaign in August of 1941 due to a sermon by a Bishop Clemens August Graf von Galen of Munster (Hereinafter Galen), (1878-1946). In August 1941 Galen gave his sermon and then arranged copies of his sermon to be widely distributed. The public disquiet was so clear that Hitler then ordered that the Euthanasia campaign be halted shortly after Galen gave his sermon. Thus many lives were saved and a brutal regime was forced to back away from its plans to kill even more. It is a nice appealing story which is however so distorted as to be a lie.2

The so-called Euthanasia murder policy had been set in motion in August of 1939 its purpose was to kill, mentally and physically handicapped individuals deemed to be burdens on the state and the most common description of the individuals marked for destruction was “useless eaters”.3 Already the Nazi state had sterilized more than 360,000 individuals and was proceeding to the next step.4

Sometime in early 1939 Hitler gave oral instructions to begin the killing of handicapped children, later in the year sometime in August 1939 and again orally Hitler gave orders to begin the killing of handicapped adults.5

During all this there was a considerable amount of preparation and planning done before the mass killings began, which took time but already some killing was already taking place.6 The killing of children was called Kdf and the murder of adults was called T-4. Those were the names of the programs for the murder of the mentally ill in Germany they do not include the murder of the handicapped in areas outside of Germany.

In fact the first mass killings of the mentally and physically handicapped occurred shortly during and shortly after the invasion of Poland. Beginning on September 22, 1939 and continuing for a few weeks c. 2000 mental patients from various Polish asylums were murdered in a wood near the town of Kocborowo. They were shot by specially trained SS death squads. In a grim forecast of what was to come inmates from a hospital in the town of Owinska were stuffed into a sealed room and killed by carbon monoxide gas. The massacre of mental and handicapped patients continued until more than 12,000 had been killed.7

When August 1939 Hitler gave the go ahead to start the mass murder of the handicapped it took some time for the program to set up. However it started in 1940 and continued well into 1941.

Although they used a variety of methods, like injections, starvation etc., the chief method of murder was gas. People would be sent too frequently by bus or truck to one of 6 different facilities and then after being “processed” they would be murdered by gas, in specially constructed chambers.

Now it is known that operation T-4 had a goal of terminating the lives of c. 70,000 people which was the goal that the Nazi’s, in this case specifically Hitler, selected for the program.8 The program was also centralized in terms of co-ordination and control and most of the killing in 1940-1941 was done in 6 centralized facilities. The program of murder was subject to bureaucratic centralized control and many if not most of the people staffing the program were Nazi fanatics or at least psychopathic in their attitudes towards their victims.9

The killing centers were Grafeneck, Brandenburg, Hartheim, Sonnenstein, Bernburg and Hadamar. The inmates were told by the staff arranging them to be murdered, various stories, like they were going out on an excursion, that they were going to be medically examined and such like to put their minds at ease. At Hadamar the victims, who had been taken to the facility in buses, usually grey painted postal buses, were disembarked in one of a series of wooden garages and taken to the main building via a specially constructed wooden corridor. In the main building they were undressed and given military overcoats and then examined by a Doctor who would help in thus fabricating plausible causes of dearth to give to their loved ones.

The victims were then escorted into the basement / cellar. They were told they were going into a shower and jammed 60 at a time, into a small room and there by the turn of valve they were gassed to death by carbon monoxide gas. The victims took up to an hour to die. Experiencing terror, panic and the symptoms of carbon monoxide poisoning, such as severe headaches, dizziness, nausea, and shortness of breath. It was not a pleasant death.

After fans got rid of what was left of the gas, “disinfectors”, cleaned up and disentangled the bodies. Those who had been marked before hand of potential interest would be autopsied in another room and their brain or other organs of interest sent to various Universities for more research. Gold teeth would of course be removed. The bodies were then burned in crematoria and the ashes randomly distributed into urns to be sent to the family. Bones would be crushed, if they did not fully burn.

People could see the thick cloud of ash from the asylum chimney after each transport to Hadamar and quickly but two and two together. Arrangements were made for families to have Urns with ashes and to deceive them into thinking the ashes came from near were the patient had been in an asylum. Further Doctors had ready a list of 62 possible reasons for death to send to the relatives of the deceased giving the fabricated “reason” for their loved one’s death. They used a carefully designed form letter that had space for a few personal details, to send these lies to the bereaved. Enclosed with this fraudulent letter would be 2 death certificates listing the false cause of death.10

Sometimes it is best to let the facts speak for themselves. I have nothing to add to the above description.

The six killing centers murdered the following numbers of people between 1940-1941.

Grafeneck – 9,839

Brandenburg - 9,772

Hartheim - 18,269

Sonnenstein - 13,720

Bernburg – 8,601

Hadamar - 10,072

Total - 70,273 11

Now the figures listed above are only for German patients murdered in Germany and exclude those murdered abroad; for example those killed in Poland. In this phase of the killing program it is rather sickening to report that c. ½ of the victims were in private or ecclesiastical institutions. It just wasn’t the state institutions that were corrupted by this murderous idea but private institutions including those run by various churches.12

The corrupting ideology behind the Euthanasia murder program was eugenics the idea that lives of certain classes of handicapped individuals were devoid of value and burden on the community at large and so ought to be terminated. The language of Euthanasia was used, but it was not allowing people, legally competent, who suffered from debilitating or terminal diseases to consent to or in fact take those own lives but simple murder. It can be stated without contradiction that “Euthanasia” was used as a smoke screen to hide the fact that it was murder. The fact that those carrying out the murders went to extraordinary efforts to deceive both patients and their families indicates that the killers knew that they were engaged in murder pure and simple.13

Has mentioned above in late August 1941 Hitler gave a stop order for T-4 and this was shortly after Galen gave a sermon and distributed copies of a hard hitting sermon. Not surprisingly many people have assumed a link and in fact they are not wrong, however they are wrong to assume it stopped the killing. The story of Galen’s sermon is as follows.

Galen was made Roman Catholic Bishop of Munster in 1933 and from the get go had a rocky relationship with the Nazis, who he regarded has upstart oafs. He was especially offended by what he saw as Nazi attacks on the church. It appears that Galen had been in receipt of information regarding the Euthanasia program since July 1940, but kept quiet for the time being. It is not completely clear why he kept quiet although it appears that like other members of the Church hierarchy who knew about the program he was concerned that any protest would simply backfire on the church. It appears that he considered going public in August 1940 but was talked out of it by Cardinal Bertram who was concerned about the possible negative effect on the church.

In July 1941 Galen was incensed about the seizure of Jesuit property in Munster by the Gestapo for state purposes decided to act.14 On August 3, 1941 Galen gave his sermon. In it he said:

If you establish and apply the principle that you can kill “unproductive” human beings, then woe betide us all when we become old and frail! If one is allowed to kill unproductive people, then woe betide the invalids who have used up, sacrificed and lost their health and strength in the productive process. If one is allowed forcibly to remove one’s unproductive fellow human beings, then woe betide loyal soldiers who return to the homeland seriously disabled, as cripples, as invalids …Woe to mankind, woe to our German nation, if God’s holy commandment “Thou shalt not kill!”, which God proclaimed on Mount Sinai amidst thunder and lightening, which God our Creator inscribed in the conscience of mankind from the very beginning, is not only broken, but if this transgression is actually tolerated and permitted to go unpunished.15

We are not talking here about a machine, a horse, nor a cow …No, we are talking about men and women, our compatriots, our brothers and sisters. Poor unproductive people if you wish, but does this mean that they have lost their right to live?16

The Nazis were infuriated by Galen’s sermon and seriously considered arresting him and sending him to a concentration camp. Galen’s sermon was made illegal and possession of copies of it a crime and several people associated with the production, creation and distribution of the sermon jailed or sent to concentration camps along with people who had it in their possession. Copies were smuggled out of Germany and the allied powers dropped copies of it over German cities. There was even before Galen’s sermon a serious level of unease over the Euthanasia program, despite the effort to conceal and hide it. The Sermon raised the level of public awareness and unease. Creating a problem for the Nazis. Which wasn’t helped by the fact Galen tried to have murder charges levelled against some of those involved.17

Hitler was furious but decided to bide his time. Hitler said:

I am quite sure that a man like the Bishop von Galen knows that after the war I shall extract retribution down to the last farthing. And if he does not succeed in the meanwhile in getting himself transferred to the Collegium Germanicum in Rome, he may rest assured that in the balancing of our accounts no “t” will remain uncrossed, no “i” left undotted.18

Fortunately for Galen Hitler and the Nazis lost the war and were therefore unable to extract vengeance on him.

Aside from infuriating Hitler and creating problems for the Nazis just what effect did Galen’s sermon have on T-4 and the Euthanasia killings? It appears that it played a role in stopping the program, so that Hitler gave a oral stop order in late August 1941, but was not the sole reason and probably not as important as two other reasons. First the T-4 killings had already achieved their goal in terms of the number of killings. Secondly the personal associated with T-4 were needed for the vastly greater killings being planned for in the east, of which the so-called Final Solution, was just a part.19

Also Kdf, the murder of children, was continued on Hitler’s express orders. Also continued was the murder of Concentration camp inmates and prisoners, under the Euthanasia banner called 14f13. Finally only the T-4 program stopped, not the killings. Instead of a centralized bureaucratic system with a few killing centers the program was decentralized and a lot was left to local initiative, strongly urged by the state.20

This is the so-called period of “Wild Euthanasia”, in which the killing was to a large extent decentralized and left to local initiative. The preferred methods of killing was not the mass gassing of the previous period but hunger and / or drug overdoses. Basically patients were frequently starved to death or deliberately given diets that caused severe bodily deterioration so that moderate injections of drugs would kill them.

This included such practices as feeding the patients diets without protein or other essential foods like fats, so that they would die more easily. Sometimes patients were simply, starved to death by not being fed at all. The usual deception and lying was done to conceal how the patient actually died from the bereaved relatives. This campaign continued right until the end of the war.21

An example of how “efficient” “Wild Euthanasia” could be is that between August 1942 and March 1945 4,817 patients were sent to Hadamar of those 4,442 died. A death rate over 90%.22

The records that were kept for the “Wild Euthanasia” killings are not very complete but it appears to have been considerably more than were killed in T-4. The absolute minimum figure seems to be 100,000.23

Aside from those killed above in both the T-4 gassing's and “Wild Euthanasia” there were those killed by starvation and / or medication before the end of T-4 those numbered c. 20,000. To this must be added those killed in KdF at least 5,000 and those killed in 14f13 c. 20,000.24

The above figures total 215,000 people murdered, and this figure is probably too low, and even so they do not include the tens of thousands non-Germans killed in the Euthanasia program in areas conquered by Germany. For example the over 10 thousand killed in Poland in 1939-1940, or the over ten thousand killed in the Soviet Union or the c. 40,000 killed in France. It appears that only c. 40,000 mental patients survived the war in Germany.25

Thus this series of programs, under the Euthanasia euphemism, altogether murdered at least 275,000 human beings and the actual figure is probably over 300,000. Compared to other massacres carried out during World War II by the Nazis this may seem small but remember it is over a ¼ of a million human beings and probably close to 1/3 of a million.

At most c. 95,000 were murdered before the stop order of August 1941 most of the victims were murdered, even in Germany, after the stop order was given. The stop order was not to stop the killings but to stop the mass gassing's of inmates. The killing was ordered to go on by other methods and did so with great, indeed horrible success.

Galen’s very brave public statement although infuriating to the Nazi authorities and very embarrassing did not stop the killing. What it helped to stopped was a particular mode of killing that it must be remembered had already achieved its stated goal when it was stopped and further its practitioners were being prepared for another campaign of murder so that they were willing to for gore for the time being. Also as I’ve said before the killing did not stop at all it went on and on using other methods. Galen’s protest despite postwar myths did not stop the Euthanasia campaign. That particular hopeful myth must be laid to rest. To quote:

Hitler’s stop order of August 1941 did not end the destruction of those considered “unworthy of life.” The belief that his stop order ended the killings is based on postwar myth. The stop order applied only to the killing centers; mass murder of the handicapped continued by other means. Moreover the stop order did not apply to children’s euthanasia, which had never utilized gas chambers. As with children, after the stop order physicians and nurses killed handicapped adults with tablets, injections and starvation. In fact, more victims of Euthanasia perished after the stop order was issued than before.26

1. I’m relying on my memory since it has been 30+ years since I’ve seen the movie.

2. An excellent example of this myth is A Lost Chance to save the Jews, in The New York Review of Books, April 27, 1989, by Conor Cruise O’Brien at Here. See also O’Brien’s response to a letter critiquing his view of the stop Euthanasia order at Here, dated October 26, 1989.

3. Chorover, Stephan L, From Genesis to Genocide, MIT Press, Cambridge MASS, 1979, quoted on p. 101.

4. Evans, Richard J., The Third Reich at War, Penguin Books, London, 2008, p. 77.

5. Friedlander, Henry, The Origins of Nazi Genocide, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill NC, 1995, pp. 39-41, 62-64.

6. Burleigh, Michael, Death and Deliverance, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994, pp. 93-129, Friedlander, pp. 62-80, Evans, pp. 77-90, Muller-Hill, Benno, Murderous Science, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1988, pp. 39-45.

7. Evans, pp. 75-77.

8. IBID, pp. 99-100.

9. Burleigh, pp. 93-161, Muller-hill, pp. 39-65.

10, Burleigh, pp. 144-153, Friedlander, pp. 107-110.

11. Friedlander, p. 109.

12. Burleigh, p. 173.

13. IBID, pp. 43-92, 183-219, Friedlander, pp. 23-38, Chorover, pp. 93-104, Muller-Hill, pp. 7-13, Lifton, Robert Jay, The Nazi Doctors, Basic Books Inc., New York, 1986, pp. 22-44.

14. Burleigh, pp. 175-178.

15. IBID, quoting Galen, p. 178.

16. Lifton, quoting Galen, p. 94.

17. Burleigh, pp. 178-180, Evans, pp. 97-101, Lifton, pp. 90-95.

18. Burleigh, quoting Hitler, p. 178.

19. Friedlander, pp. 151-163, Lifton, pp. 135-148, Evans, 100-101, Sereny, Gitta, Into That Darkness, Andre Deutsch, London, 1974, pp. 79-90.

20. Friedlander, pp. 39-61, 131-163, Lifton, pp. 96-102, 134-146, Burleigh, pp. 93-129, 220-266, Evans, pp. 524-530, Muller-Hill, pp. 15, 63-65.

21. IBID.

22. Evans, p. 527.

23. Muller-Hill, p. 65, Friedlander, p. 151, Chorover, p. 101.

24. Lifton, p. 142, Friedlander, pp. 61, 150.

25, Muller-Hill, p. 65, Evans, 528-530, Burleigh, pp. 220-237, Friedlander, pp. 151-163, Chorover, p. 101.

26. Friedlander, p. 151.

Pierre Cloutier

Friday, April 09, 2010

Frederick II and the Outbreak of the Seven Years War.

Frederick is called the “Great” because he was successful at war, or should I say thought to be successful at war, and because he succeeded in conquering territory and making Prussia one of the great powers of Europe. Basically he is a “Great” man because he succeeded. The actual manner by which he achieved his success and the cost of his success for others is as per usual in these things downgraded / ignored. This worship of military success leads to the idea that Frederick was “Great” in all sorts of things and a fawning, hero worship that writhes in ecstasy at his “glorious” victories and genuflects at his shrine.3

One can go into the rather puzzling question about how a King who massively strengthened the militaristic nature of the Prussian state, and its Police State apparatus and in effect completed the process of turning the Prussian state from a State with an army to an Army with a State could for a moment fool anyone into thinking he was an “Enlightened” monarch. But then military success does tend to dazzle. But then Frederick easily put on “enlightened” airs and dazzled the literati of his day with a lot of words and pretty speeches about “enlightened” values while increasing the subordination of society to the state and its army. That Frederick was also incredibly vain, arrogant and loath to take responsibility for things if things went wrong, (blaming other people was a fine if childish art with Frederick). That Frederick was also in many respects a reckless diplomat and frequently engaged in political and other acts of fairly dubious morality is often forgotten.4

For example when Maria-Theresa inherited the Austrian throne in 1740, Austria had been going through a long term period of decline and it was only with difficulty that Maria-Theresa’s father Charles VI was able to arrange for the myriad domains of the house of Habsburg to accept the succession of his daughter Maria-Theresa; who became the only female ruler of the house of Habsburg. This so-called Pragmatic Sanction was then accepted by the various major powers of Europe through the tireless diplomacy of Charles VI who was anxious to avoid a diplomatic crisis upon the accession of his daughter. Also there was his concern that the other powers would seek to take advantage of Maria-Theresa’s accession to attack Austria and attempt to partition the empire between them.

Despite the anticipation of crisis Maria-Theresa succeeded her father in 1740 and at first it looked as if the various powers would accept the Pragmatic Sanction and let Maria-Theresa reign in peace. Frederick who had recently come to the throne of Prussia decided that given that so many powers were just waiting to attack Austria and carve her up that he would start the whole process, this was after he had signed a treaty saying he would respect the Pragmatic Sanction.5

The result was the war of Austrian Succession an interminable 8 year war during which Prussia was able to wrest the province of Silesia from Austria. Despite the serious decay of Austrian institutions and military during Charles VI’s reign, (Charles was a good diplomat but not a good administrator and Austria fell behind and looked like ripe pickings for the other powers), Maria-Theresa, who had not been educated or trained in any fashion to rule proved to be a very capable if not great ruler, and despite her almost total lack of experience rose to the challenge.6

Frederick went to war, made peace and unmade alliances almost at will with little regard to any moral imperatives or even his word. Frederick blithely betrayed his allies twice by making separate peace treaties with Austria and broke his agreements with Austria with equal facility. In the end though Frederick ended up with Silesia a province that increased the population of Prussia by more than 50% and a even larger increase in wealth. In fact Prussia’s pretensions of being a great power were dependent on possession of Silesia.7

Frederick had inherited from his father, Frederick William I, (a man whose behavior indicated a psychopathic personality), an excellent, large standing army that by means of the most draconian exploitation of the country he was able to extract from his fairly small country. Frederick had great ambitions and from the first wanted to take Austrian lands to further those ambitions.8

Austria was able fight off this attempt to partition her. Aside from Silesia Austria lost very little territory. But the war convinced Maria-Theresa of the urgent need to reform and revitalize the state. As an “enlightened” monarch Maria-Theresa easily puts Frederick in the shade and unlike him the challenges that she faced and difficulties she had to overcome were quite significantly greater. Further unlike Frederick Maria-Theresa had real moral scruples which did affect her behavior and policies. The idea of subordinating the state to the army was anathema to her. If Maria-Theresa had inherited a ramshackle state she was with remarkable skill able to hold the great majority of it together despite everything.9

Despite the ohhs and awws of the literati Frederick’s double dealing in this period had left a bad taste in the mouths of many including that of Frederick’s allies, especially France. Although many were dazzled by Frederick’s military victories, Frederick had a serious enemy in Maria-Theresa, who wanted Silesia back and it would have been prudent for Frederick to make every effort to remain an ally of France in order to hold Austria back from a war of revenge. Well to put it bluntly Frederick muffed it.10

The story of the long diplomatic intrigues that eventually resulted in the alliance of Russia, France and Austria against Prussia belongs in another essay suffice to say Frederick proved a clumsy and basically inept diplomat at the time. The fact that he was suspected of having further massive territorial designs especially on the lands of the Austrian monarchy, which were in fact true, increased the determination of Maria-Theresa to cut him down to size. Prussian schemes to annex parts of Poland increased Russian anxieties and France was utterly infuriated by Frederick’s behavior during the war of Austrian Succession and felt it could not trust him at all.11

In the end France, reversing a policy of long standing (centuries) signed an alliance with Austria and Russia joined in. Now this alliance, which was only formalized after Frederick attacked Saxony, was defensive in nature and frankly neither France nor Russia was really all that interested in a war to gain Silesia back for Austria, but all three powers were determined to contain Prussia, and its King who they viewed as a loose cannon liable to go off in any direction.12

Frederick muffed it again. In 1756 he invaded Saxony and then Austria deliberately starting a war with France, Austria and Russia.

Faced with a circle of enemies Frederick decided to attack. Frederick’s defenders have from that day to this have defended his action as a preventive strike designed to anticipate his enemies and hence a move a great boldness.

Further Frederick is congratulated for trying to break up his enemies by attacking first and trying to drive Austria out of the alliance and thus breaking up the coalition against him. This is of course to take Frederick’s self serving apologia at face value. What is forgotten is that Austria, Russia and France had a defensive alliance not an offensive one. Neither France nor Russia were terribly eager to fight a war solely for Austria to get back Silesia. Further Frederick attacked Saxony an ally of Austria, not Austria. What is forgotten is also that Frederick did indeed want to defeat Saxony and Austria quickly, and then impose on both a peace that would satisfy his long standing desire for much more territory from both of them. In other words Frederick attacked Austria and Saxony in order to extract from both has much territory as possible not just to break up a coalition against him. He also had plans to impose a heavy indemnity on both. What happened is that both Russia and France pursuant to their alliance with Austria declared war on Prussia. Thus Frederick had, with great efficiency, created a powerful coalition against himself.13

Having thus set himself up for failure and being crushed by a much more powerful coalition, Frederick would spend most of the next seven years desperately trying to save himself from the predicament he had so expertly put himself in. Needless to say the Frederick gawkers would spend centuries afterwards writhing in ecstasy at Frederick’s “greatness” in holding off a much more powerful coalition and repeating Frederick’s self serving apologia that the war was inevitable and that he was thus justified in attacking first, carefully avoiding the fact that the so-called inevitable attack was NOT inevitable. Further that Frederick’s behavior was in effect a self fulfilling prophecy and that Frederick had very ambitious territorial ambitions, against Austria, Saxony and Poland, which he was most anxious to satisfy. In other words Frederick's attack was an act of aggression designed to seize territory, at least in part.14

It takes real incompetence to put your head in the noose the way Frederick did. Frederick in the end was only saved one of the most bizarre strokes of good fortune ever, for which he could take no responsibility. Another time I will go into that stroke of fortune. Meanwhile the people of Prussia, Saxony, Austria, Russia, Germany, and France would pay for Frederick’s incompetent diplomacy, lack of scruple and ambition in spades.15

1. The number of suck-up biographies of Frederick the “Great” is legion perhaps the most stomach turning, at least in English, is Carlyle, Thomas, History of Frederick the Great, Six Volumes, Robson and Son, London, 1858-1865. Google Books, Here, see also Fuller, J. F. C., A Military History of the Western World, v. 2, DaCapo, New York, 1955, pp. 192-215.

2. Szabo, Franz A., The Seven Years War in Europe 1756-1763, Pearson, Longman, London, 2008.

3. See Carlyle above and Duffy, Christopher, Frederick the Great: A Military Life, Routledge, London, 1985 for many examples.

4. See Duffy, pp. 195-196, Szabo, pp. 87-88, 238-240, 253-255, Williams, E. N., The Ancien Regime in Europe, Penguin Books, London, 1970, pp. 372-398, Waite, Robert, G. L., The Psychopathic God, Signet, New York, 1977, pp. 306-311, Ogg, David, Europe of the Ancien Regime 1715-1783, Harper Torchbooks, New York, 1965, pp. 212-217, Hufton, Olwen, Europe: Privilege and Protest: 1730-1789, Fontana Books, London, 1980, pp. 191-219.

5. IBID, Waite, Williams, pp. 430-432, Ogg, pp. 124-127.161-168.

6. No really good biography of Maria-Theresa exists in English, but see Williams, pp. 435-459, Ogg, 206-211, Hufton, pp. 160-73.

7. Hufton, pp. 191, 206.

8. See Williams, pp. 335-351, Waite, 306-307, Williams, 376-378, Hufton, 205-206, Ogg, 161-168.

9. Ogg, pp. 210-211, Williams, 435-459, Hufton, 160-173.

10. Williams, pp. 437-438, Ogg, pp. 138-143, Duffy, pp. 82-85, Szabo, pp. 8-18.

11. IBID.

12. IBID.

13. IBID, and Szabo, pp. 10, 37, 82.

14. IBID.

15. Duffy, pp. 242, 244, Hufton, pp. 211-212. Prussia for example lost 400-500 thousand people.

Pierre Cloutier

Saturday, March 13, 2010

In fact defenestration in my experience, with one exception,2 I’ve only seen it used to describe two separate events and no others. In fact it is like this word was only invented to describe those events and not to describe any other event involving throwing someone out a window. The two examples occurred in the same city and in both cases marked the start of some rather brutal, long wars. I am referring to the First, (1419 C.E.) and Second (1618 C.E.) Defenestrations of Prague.

The Second Defenestration of Prague was in deliberate imitation of the First Defenestration of Prague and was the event that marked the start of the interminable and quite horrible Thirty Years War. I may discuss it at another time.3 The First Defenestration marked the start of another long war that is not well known in the English speaking world; the Hussite Wars. A long, very bloody, precursor to both the Protestant Reformation and the ghastly religious wars that followed.4

Some other time I will discuss the Hussite Wars. Here I will go into a bit of the background and the actual events of First Defenestration of Prague.

The setting for these events is what today we call the Czech Republic. In those days it was a Kingdom with 5 parts. The kingdom of Bohemia, the Margravate of Moravia, Silesia and Upper and Lower Lusatia.5 All of those lands were considered the Lands of the Bohemian crown. Furthermore they were ruled in 1419 by the family of the House of Luxembourg in this case by King Wenceslas IV. Now Wenceslas IV was a son of Charles IV who was not just King of Bohemia but also King of Germany and hence Emperor. (Reign 1346-1378 C.E.) He was also a strong monarch and an incredibly successful one. Unfortunately he decided upon his death that his various holdings would be divided among his various sons and relatives the result was disaster.6

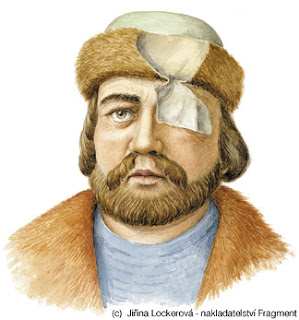

German Emperor

The reason that conflict was simmering was an escalating religious crisis. Bohemia was probably the area in Western Europe that had the biggest and most intense concentration of land in the hands of the Church. In 1410 this amounted to c. ½ of the land.10 Much of it in the hands of various orders like the Dominicans and Franciscans, who also commanded immense wealth in coin, jewellery, bullion and were heavily involved in trade and commerce. This wealth was deeply resented by large sections of the population that felt pressured by Church wealth and power and felt that Church possession of so much wealth curtailed their own economic opportunities. Of course there was also the desire to seize Church property, by a resentful Nobility and Peasantry who felt the market for buying agricultural land much reduced by the Church owning so much of it.11

If greed for Church property along with resentment of Clerical power and wealth was one part of the reason for resentment, the other was a long standing religious revival.

Beginning in the mid 14th century Bohemia had been the center of a movement of religious reform and revival centering on the reformation of the Church, by clearing away corruption and incompetence and a reformation of manners of the laity. As the 14th century went on attacks on the corruption and incompetence and greed of the institutional Church increased in frequency and vitriol. Added to this were such events as the Great Schism (1378-1420 C.E.) which divided Western Christianity over who was Pope. Some countries recognizing the Pope in Avignon as Pope and others the Pope in Rome. The resulting struggle was characterized by much brutality and corruption which reduced the prestige of the papacy to a very low level, and served to massively highlight the corruption and worldliness of the Church. The result was a renewed emphasis that the Church needed to be reformed and cleansed of corruption and purified by returning to the standards of the earliest Church. This meant in practical terms divesting the Church of its wealth, getting rid of debauched, corrupt and ignorant clergy and a re-dedication to the strict standards of early Christianity.12

Thus during this time the works of the great English theologian John Wycliffe, (c. 1325-1384 C.E.) with their call for Church reform and the stripping of the Church of its wealth, which was deemed a corrupting influence, was heard in Bohemia. Beginning in the 1390’s Wycliffe’s works were being read and considered in Bohemia.13

Added to this religious stew was the very real, proto-nationalist, resentment by the Czech people against German influence in Bohemia. The longstanding fear that the Germans would eventually destroy the Czech people. The fact that the various religious orders were dominated by Germans along with the much of the state and Church bureaucracy did not help matters. The reform movement was considered both deliberately and incidentally a way of reasserting Czech identity. The fact that the reform movement preached largely in Czech played a role also.14

The great Czech reformer Jan Hus, (c. 1372-1415 C.E.) heavily influenced by Wycliffe, as indicated by his own writings preached in Prague at the Bethlehem chapel, starting in 1402 C.E.) where deliberately the preaching was in Czech. Although he enjoyed the protection of Wenceslas IV and his wife Queen Zofie, Jan Hus was in constant trouble with other church officials and accused of heresy. His sermons, and those of his followers, attacking the Church and calling for both Church and moral reform were however popular along with his call for the Church to be stripped of its wealth. Eventually Hus was forced into exile in southern Bohemia where he passed the time giving popular outdoor sermons and writing his main theological and institutional works.15

Meanwhile the Great Schism was giving rise to in Bohemia and other places to the feeling that the last days were about to come and that the return of Jesus was imminent. This millennial expectations were both strong and popular and were shared to lesser or greater degree by Jan Hus and some of his followers.16

Hus had by this time a lot of enemies in the Church who wanted his voice to be silenced, he also had achieved for himself and his followers a formidable list of Clerical / Noble supporters in Bohemia and Moravia who were on his side.

During this a Church Council (1414-1418 C.E.) was put together, to a large extent by Sigismund, King of Hungary and German Emperor, to try to heal the Great Schism and it meet at Constance on Lake Constance next to modern day Switzerland. It did eventually succeed in healing the Great Schism by getting the 3 (yes three!) then Popes to resign and electing a new one. It also quite un-intently ignited a religious war. Sigismund was prevailed to give a safe conduct to Jan Hus so he could go there to defend his views and call for reform of the Church. There Jan Hus was arrested, tried and burned at the stake for heresy on July 6, 1415. Sigismund’s refusal to carryout his promise of safe conduct and the farcical trial, along with the argument used that promises given to heretics do not have to be kept are all morally repellent to the highest degree.17

With the support of the King and Queen the Supporters of Jan Hus gained control of Church in Bohemia. The result was a continued struggle over the Church as the Council and Sigismund tried to regain control. Sigismund was by this time looking forward to succeeding his childless brother has King of Bohemia and he felt he needed Church support.

The struggle of the reformers took the form of Utraquistism, from a Latin expression meaning in / under both species or kinds. It referred to the practice of giving to the laity communion in the form of both the bread and the wine. In the west this practice had almost completely disappeared by the early 15th century, replaced by simply giving the bread. However the new movement felt that the process of reform back to an earlier, purer form of Christianity required the return to giving wine to the laity. The fact that Eastern Orthodox Christianity had kept the practice also played a role in the adoption of the practice. The result was that the Chalice from which the laity received the wine became the symbol of the movement now called Hussitism from the name of its martyred founder.19

Rage against the council for the death, (actually judicial murder) of Jan Hus played a role and the rage was increased when Jerome of Prague, one of Jan Hus’ colleagues who had gone to Constance to defend Jan Hus was himself burned at the stake on May 30, 1416. C.E.20

The result was that by the end of 1416 C.E., the Hussite movement had captured the Church in Bohemia and there were already murmurs that a Crusade would have to be waged to crush the “Heretics” in Bohemia.21

The next couple of years were a long and rather tedious series of internal struggles and conflicts with the Church trying to by various means to suppress the Hussite movement and the nobility being divided and king Wenceslas IV and his wide Zofie although basically supporting the Hussite cause trying to reign in the radicals. For it was the radicals who began to define the movement.22

By early 1419 pressure from the Church, which included an economic blockade and threats to invade Bohemia in the guise of a Crusade had become very great. Inside Bohemia a wave of religious and revolutionary enthusiasm had spread through out much of the country. By this time radicals called Taborites had established themselves throughout much of southern Bohemia. There was the widespread belief that the last days had come and the second coming was approaching and that the Church of Rome was the Antichrist.23

Terrified by the forces unleashed Wenceslas IV and queen Zofie tried to reign in the Hussites. First Hussite services were restricted in Prague and regular Catholic services were allowed, (after being prohibited in reaction to Jan Hus’ murder). This increased unrest and significant opposition. On July 6th 1419 the king purged the government of the New Town, (part of Prague and a Hussite stronghold) of Hussite supporters and replaced them with anti-Hussites. Several Hussite supporters were arrested. The stage was set for a show down.24

On July 26th 1419 C.E. Jan Zelivsky gave a heated sermon at St Mary’s in the Snow part of which is as follows:

Thus does Jan Zelivsky pour his contempt on the official Church and its supporters and at the end of his sermon lists the miracles that God has performed for his followers:Indeed, dogs in our own time eat the consecrated bread and the holy charity which belong to the poor. It is given in tumblers to sorcerers, to their servants, and to their servants and to his dogs. All those who eat the bread of the sons act against the truth just like dogs who pounce on a bone.26

…Tobias healed of blindness with the gall of a fish, Daniel saved from the den of lions and Jonah from the stomach of a whale. Christ was born of a virgin, water was changed into wine, three young people were raised: the daughter of Jairus, the widow’s son at the town gate and Lazarus from his tomb. Behold, what an abundance of wonders!27

The pro-Hussite council of the Old Town of Prague and various Hussite supporters of the royal court apparently went along with the coup or actively took part in it. Wenceslas IV was enraged and apparently had a stroke. It appears that he came around to accept the fait accompli but on August 16, 1419 he had another stoke and died.30

There was a problem Wenceslas IV’s heir was his brother Sigismund, who was, not surprisingly, considered responsible for the murders of Jan Hus and Jerome of Prague, who had made repeated statements about crushing heresy in Bohemia and whose entire political career indicated that he was not to be trusted given his continual intrigues, to say nothing about his broken promise to Jan Hus, against his brother Wenceslas IV. Unfortunately his undoubted legitimate claim to the Bohemian throne along with the fear of radical Hussitism gave Sigismund a firm foothold in Bohemia. The result was the truly terrible Hussite wars (1419-1434 C.E.) characterized by revolting brutality and no less than 5 Crusades against the Hussites all of which failed. It was a combination of civil war, Crusade, war of national independence on the part of the Czechs, social revolution, dynastic war and pillaging expeditions.31

Concerning some of the people mentioned in this posting; Jan Zelivsky was executed in 1422 in the midst of faction fighting for the control of Prague. Jan Ziska died in 1424 while besieging a fortress.32

During the war the Czech Hussites created a truly frightening and effective war machine, largely through the genius of the one eyed and later blind Czech general Jan Ziska. Eventually a combination of internal disorder among the Hussite and the failure to crush the Hussites militarily forced the acceptance of a compromise peace. Eventually Sigismund was accepted as king, (in 1436 C.E.), he did not enjoy his kingdom long and died in 1437 C.E., duplicitous to the end.33

Perhaps at another time I will post some more about the Hussite Wars which were in many respects a dress rehearsal for both the Reformation and the Religious wars that followed.

1. Those plastic things at the end of shoe laces.

2. A friend of mine out of the blue used the word in conversation, correctly I might add. Aside from that case I’ve never heard the word in conversation ever.

3. Wedgewoood, C.V., The Thirty Years War, Penguin Books, London, 1938, pp. 73-75. Parker, Geoffrey Editor, The Thirty Years War, Second Edition, Routledge, London, 1997, p. 43, Polisensky, J. V., The Thirty Years War, New English Library, London, 1971, pp. 103-105.

4. Polisensky, pp. 31-32, Parker, p. 7, Cohn, Norman, The Pursuit of the Millennium, Revised Edition, Oxford University Press, 1970, pp. 205-213.

5. Heymann, Frederick G., John Zizka and the Hussite Revolution, Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ, 1955, map p. 2, see also Czech Lands in Wikipedia, Here.

6.Heymann, pp. 38-39, Kaminsky, Howard, The Hussite Revolution, University of California Press, Berkeley CA, 1967, pp. 7-9.

7. Heymann, pp. 23-29.

8. IBID, pp. 36-38, See Wenceslaus, King of the Romans in Wikipedia Here.

9. Heymann, pp. 28-29, 36-38.

10. IBID, p. 39, Cohn p. 205.

11. IBID, pp. 39-43, Kaminsky, pp. 33-34.

12. Kaminsky, pp. 5-55.

13. Kaminsky, pp. 23-35.

14. Kaminsky, pp. 7-22, 35-55, Heymann, pp. 51-60.

15. IBID, Cohn, pp. 205-212. See also Hus, Jan, Letters of Jan Hus, William Whyte and Co. Edinburgh, 1996.

16. IBID, Kaminsky, pp.161-179, 310-360.

17. Heymann, pp. 56-58, Jan Hus, in Wikipedia Here, Lutzow, Count, The Hussite Wars, J.M. Dent and Sons, London, 1914, pp. 1-4.

18. Heymann, pp. 50-51. The number of signatories was 452 and included practically all the higher Czech nobility.

19. Kaminsky, pp. 97-126.

20. Heymann, p. 58, Bernard, Paul P., Jerome of Prague, Austria and the Hussites, Church History, V. 27, No. 1, March, 1958, pp. 3-22.

21. Fudge, Thomas A., Editor, The Crusade against Heretics in Bohemia, 1418-1437, Ashgate, Bodmin Cornwall, 2002, pp. 14-21, Lutzow, pp. 3-9.

22. Heymann, pp. 61-63, Kaminsky, pp. 265-278.

23. Cohn, pp. 205-215, Kaminsky, pp. 310-360.

24. See Footnote 22.

25. Heymann, pp. 62-63, Kaminsky, pp. 271-278.

26. Fudge, p. 23.

27. Fudge, pp. 24-25.

28. Kaminsky, 289-297, Heymann, pp. 63-65.

29. IBID.

30. Heymann, p. 66.

31. See Lutzow, Fudge Introduction, pp. 1-13, and contents, Cohn pp. 221-222 and Heymann and Kaminsky.

33. Heymann, pp. 314-315, 438-440, Lutzow, pp. 127-128, 174-175, Kaminsky, p. 460.

33. Fudge, pp. 341-401, Lutzow, pp. 337-363.

Pierre Cloutier

Thursday, January 14, 2010

Lutzen, 1632

In a previous posting I reviewed a book1 on the Thirty Years War. In the review I stated that I felt that the reputation of the Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus was seriously overrated.

In fact this inflation of reputation is such that a sort of massaging of the actual historical record is required. An excellent example of that is the battle of Lutzen, November 16, 1632, during which Gustavus Adolphus got himself killed.

Now the mythologizing about Gustavus Adolphus is to a large extent from him being celebrated by military men and his use in Military colleges and other educational institutions as a an example of military genius. For example “Gustavus Adolphus was the one great captain of this century”2. What is interesting is that the very account of Gustavus Adolphus’ own military operations in the book do not support this assessment at all.3

In the nineteenth century celebrations of Gustavus Adolphus would break all barriers and approach incredible heights of hagiography and hero worship. An excellent example is Gustavus Adolphus, by Theodore Ayrault Dodge.4

This massaging is especially necessary when describing the battle of Lutzen and in fact what happens is in effect outright falsification. However before we go into the falsification let us review what actually happened before and during the battle.

Gustavus Adolphus had after his crushing victory at Breitenfeld, September 17, 1631, gone on to undue most of the successes achieved by the Imperial armies since 1618. In fact Gustavus Adolphus seemed to have become arbitrator of central Europe and on the verge of achieving final victory over the Emperor and giving the Protestant cause hegemony in central Europe.5

Of course those dreams were mere delusions and fantasies. Gustavus Adolphus managed to alienate many of his allies, and he, himself showed a singular lack of diplomatic ability. This was not helped by the fact that the Imperialists led again by Wallenstein staged a remarkable military recovery.6

The campaign that resulted is embarrassing to those who promote the idea that Gustavus Adolphus was a “Great Captain”. In a campaign of maneuver and entrenchments Wallenstein out thought Gustavus Adolphus.

Basically Wallenstein maneuvered Gustavus Adolphus into the city of Nuremburg and so stymied him that Gustavus Adolphus, his army wasting away from disease etc., in exasperation attacked Wallenstein’s entrenched army at Alte Veste, September 3 & 4, 1632. Gustavus was defeated losing at least 2,400 casualties, (probably more than 3,000). Wallenstein lost less than 1,000. Further c. 29,000 men had died in the Swedish camp and after the battle 11,000 men deserted his army. Shortly afterwards Gustavus Adolphus retired from Nuremberg intending to winter in Swabia, in southern Germany. Wallenstein instead of going into winter quarters invaded Saxony and by threatening to cut Gustavus Adolphus’ communications with Sweden forced the Swedish King to come north.7

So far in the contest between Wallenstein and Gustavus Adolphus, Wallenstein was winning.

The Saxons had sent most of their army into Silesia and so were almost entirely defenceless when Wallenstein invaded. He very quickly occupied large areas of the duchy.8

Gustavus Adolphus with his communications threatened had no choice but to go north, he also had to prevent his most important ally Saxony from making peace or going over to the Imperials. Further Gustavus Adolphus’ prestige had been seriously undermined by the campaign so far.

In this situation Gustavus decided he had to seek and win a battle to restore his prestige and shore up his faltering system of alliances.

Wallenstein had other ideas. Winter had set in and he was dispersing his army for winter quarters. Wallenstein just did not think Gustavus Adolphus would try for battle at this time of cold and when food was hard to find. Further Wallenstein had detached c. 5,000 men under Pappenheim, (at Pappenheim’s request) to reinforce Imperial garrisons in Westphalia and Wallenstein sent 2,500 men to watch the city of Torgau. Gustavus was almost desperate for a battle and Wallenstein, very ill, did not think anyone would want to fight a battle under the conditions prevailing.

Wallenstein when he found out that Gustavus Adolphus was marching on him gathered together what troops he could. Even so he only had c. 12,350 against Gustavus Adolphus’ c. 19,200. Wallenstein not surprisingly sent urgent requests to Pappenheim to return as soon as possible.9

It is entirely in order to praise Gustavus Adolphus for surprising Wallenstein at this stage and forcing a battle with him having a numerical advantage. For once Gustavus Adolphus had outsmarted Wallenstein. Gustavus Adolphus however proceeded to lose most of the advantage gained.

First Gustavus Adolphus was delayed for one day by a small cavalry detachment and second of all Wallenstein guessed what Gustavus Adolphus would do and planned accordingly.

Swedes White, Imperials Black

The battle started at c. 10:00am in the morning when Gustavus Adolphus mounted an all out attack. This frontal attack made little progress has Gustavus Adolphus’ troops were unable to take Lutzen or the hill in front of it, (Windmill hill) where Wallenstein had posted artillery. Gustavus Adolphus’ troops were able to make progress on the other flank, but by then smoke from fire and gunpowder was making it difficult to see what was going on. About 1:00pm Pappenheim returned with 2,300 cavalry and drove the Swedes back on the flank that they had been pushing back. Pappenheim was killed in the attack. The battle now degenerated into mishmash of small units attacking and defending and both Gustavus Adolphus and Wallenstein largely lost control of the battle.

In the confusion Gustavus Adolphus was wounded twice by bullets the second wound killing him. His body was not retrieved until later. Moral in the Swedish army was adversely affected by Gustavus Adolphus’ death. It appears that at least some of the Swedish commanders suggested retreat but Bernard, a German in Swedish service, managed to get the Swedes to agree to more attacks. These attacks finally took Windmill hill and captured some of Wallenstein’s artillery.

Fighting subsided and finally ended around 5:00pm. About an hour later Pappenheim’s 3,000 infantry arrived. Wallenstein had suffered 3,000 casualties. The Swedes had suffered c. 6,000 casualties.

Wallenstein, ill and shaken by his severe casualties and unsure that Gustavus Adolphus was actually dead decided to retreat; abandoning his artillery. Interestingly the Swedes where on the point of retreat when they found out the Imperial army had withdrawn.11

So basically the battle was tactically indecisive although because of the Imperial retreat the Swedes were able to claim victory and certainly the imperial evacuation of Sweden’s ally Saxony after the battle would seem to indicate a strategic Swedish victory. However this “victory” had cost the life of Sweden’s King, created a dangerous situation in Germany for Sweden and put Gustavus Adolphus’ 8 year old daughter Christina on the throne.12

It was only Wallenstein’s retreat that allowed the Swedes to claim victory and that was likely the worst military decision Wallenstein ever made. Otherwise Wallenstein had managed to recoup quite successfully from being caught with his pants down and despite being outnumbered through out the battle, (this includes the reinforcements that arrived during it) had fought the battle to a draw and inflicted significantly greater casualties on his enemies. Gustavus Adolphus’ generalship just before and during the battle are not impressive. Gustavus Adolphus seems to have tried simply to use his large superiority of numbers to crush his enemy in an unimaginative frontal assault. Wallenstein was overall better that Gustavus Adolphus just before and during the battle. It was after the battle that Wallenstein lost it so to speak.13

Now calling this mess of a battle “a great Swedish victory”14 seems at best to be an exaggeration and most likely simply false.

Now my account of the battle is largely from Wilson’s book on the Thirty Years War,15 and it appears to be overall accurate. What do other accounts say?

Now accounts that describe the battle has a less than a stunning Swedish victory do exist and are not new.16 So this is hardly revisionism. It appears that the sources of this error are the result of a whole series of mistakes and revisions that work to inflate the Swedish kings reputation.

For example various accounts state that the Imperials either out numbered the Swedes or had equal numbers to them at the beginning of the battle. Even some of the accounts that dispute the idea of a “great Swedish victory” accept this. To give a few examples. Fuller gives Wallenstein 25, 000 men excluding Pappenheim who he says had 8,000 with him. He gives Gustavus Adolphus 18,000 men.17

The Dupuys give Wallenstein 20,000 men excluding Pappenheim’s 8,000. Gustavus Adolphus is given 18,000 men.18

Dodge says:

It is only certain that Gustavus’ army was much weaker than Wallenstein’s. It may have numbered eighteen thousand men, while the Imperialists can scarcely have had less than twenty-five thousand; and this number was to be reinforced by fully eight thousand more, whenever Pappenheim should come up.19

Wedgwood gives Swedish forces as c. 16,000 strong and gives Wallenstein including Pappenheim 26,000 men. Assuming that Wedgwood thought Pappenheim had c. 8,000 men this would give Wallenstein 18,000 men to Gustavus Adolphus’ 16,000.21

Thus Gustavus Adolphus’ actual out numbering Wallenstein by more than 50% at the beginning of the battle is turned into being slightly outnumbered or significantly outnumbered by Wallenstein. Even historians who do not buy the “great Swedish victory” myth accept part of the myth of at least equal odds at the beginning of the battle.

Further is the idea that all of Pappenheim’s 8,000 men during the battle arrived at once is stated in some accounts.22 This is false 2,300 arrived during the battle and 3,000 just after it ended. I further note that the forces Pappenheim brought to join Wallenstein did not number 8,000 but 5,300. Altogether with Pappenheim’s reinforcements Wallenstein had 17,650 men brought to the battlefield. As against Gustavus Adolphus’ 19,200 men.23

Now the matter of casualties Fuller gives the number as the Imperials losing 3-4,000 dead and the Swedes 1,500.24 Dodge gives Imperial casualties as between 10-12,000 and Swedish as comparable.25 Dupuy & Dupuy, give Imperial casualties has c. 12,000 and Swedish has c. 10,000.26 Parker gives the Imperial dead has 6,000 but gives no other casualties.27

The above figures have one thing in common they greatly inflate the actual casualties of the battle. As indicated above it appears that Swedish casualties were about double Imperial (6,000 against 3,000). Given the size of the armies involved these are certainly severe losses. But the figures giving more Imperial losses than Swedish are simply wrong and part of the effort to inflate the battle as “a great Swedish victory”. In fact rather than inflicting more losses than they suffered the Swedes in fact suffered double the losses of their enemy. But of course in order for it to be “a great Swedish victory” casualties must be large and the "loser" must lose more than the "winner".

Finally accounts of the battle must be amended Fuller for example says:

The King’s body was recovered, Wallenstein’s guns were retaken, then lost and captured again, but after this the Swedes carried all before them and the Imperial army broke up and scattered as night crept over the field.28

One more effort was made for the manes of the dead hero, and the charge was given with the vigor of loving despair. The decimated ranks of the Northlanders closed up shoulder to shoulder, the first and second lines were merged into one, and forward they went in the foggy dusk, with a will which even they had never shown before. Nothing could resist their tremendous onset. On right, centre, left, everywhere and without a gap, the Swedes carried all before them. The imperial army was torn into shreds and swept far back of the causeway, where so many brave men had that day bitten the dust. At this moment some ammunition chests in rear of the imperial line exploded, which multiplied the confusion in the enemy's ranks. Darkness had descended on the field; but the Swedes remained there to mourn their beloved king, while the imperial forces sought refuge from the fearful slaughter and retired out of range.29

Lutzen has been called a drawn battle. It was unequivocally a Swedish victory.30

The Swedes had destroyed the last army of the emperor. At the opening of the year Ferdinand had been at the end of his resources, when Wallenstein came to his aid; and the great Czech had now been utterly defeated.31This is a collection of falsehoods. The Swedes had NOT destroyed the “last” army of the Emperor. That army was still largely intact. Further the Emperor did have other armies although Dodge does not seem aware of them. Wallenstein was NOT utterly defeated in any sense. It is arguable that Wallenstein was not defeated at all. In fact in the coming year Wallenstein although gravely ill and probably not having much time to live would reach the height of his power, before a combination of his own arrogance and double dealing would lead to him being assassinated with the Emperor’s approval in early 1634.32

Dodge was engaged in what can only be described as telling a big lie that due to constant repetition is believed by so many. In this case the lie is the alleged great victory. Well there never was a great victory at Lutzen. Instead we have a bloody inconclusive battle that ended in a sort of victory for the side losing more men because the other side withdrew from the battlefield.

Gustavus Adolphus is credited with originating many of the features of modern armies, with creating a military machine of unique sophistication vastly superior to the armies of his enemies.33 An unbiased look at his campaigns and battles reveals that this is very overdrawn. His armies were not vastly superior to his enemies. The battle of Lutzen clearly indicates that Swedish superiority was not huge and that whatever elements Gustavus Adolphus’ army had that were superior could be countered. Further it does appear that Gustavus Adolphus although a very competent general was not greatly, if at all, superior to Wallenstein as a general.34

Dodge among many others contends that Gustavus Adolphus would have imposed peace and only his unfortunate death prevented it.35 This is pure fantasizing. This is the idea of the “Great Man” as Saviour and Messiah. It speaks of hero worship and yes again of hagiography. It does not belong in sober historical writing.

Of course a lot of this reflects the stunning long term success of the Swedish and their allies propaganda system that boosted the Swedish king and his accomplishments.36

Wedgwood in her book wrote a sober assessment of Gustavus Adolphus37 that should be required reading for all those who genuflect to the ghost of Gustavus Adolphus. In it Wedgwood writes of the relief of so many of Sweden’s allies in Germany and elsewhere that the Swedish king was dead. That his inability to make or implement practical or even reasonable diplomacy would no longer screw things up; that this bull in the china shop was gone. Wedgwood concludes:

…he [Gustavus Adolphus] could break the Habsburg Empire, but he could build nothing, and he left German politics, as he left her fields, a heap of shards.38In the end peace was finally made in 1648 at Westphalia with much of the Empire in ruins and everyone exhausted.

In order to properly rate Gustavus Adolphus the battle of Lutzen must be properly evaluated and in this case what actually happened was not what so many since have thought happened. Thus did the real battle of Lutzen disappear down a memory hole to be replaced by a mythical “great victory” that never happened.

1. Wilson, Peter H., The Thirty Years War: Europe’s Tragedy, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MASS, 2009.

2. Dupuy, R. Ernest, & Dupuy, Trevor N., The Encyclopedia of Military History, Revised Edition, Harper & Row, Pub., New York, 1977, p. 522.

3. IBID, pp. 537-539, 573-574, 577.

4. Dodge, Theodore Ayrault, Gustavus Adolphus, Houghton Mifflin and Co., New York, 1895. See especially pp. 398-411.

5. Wilson, pp. 476-487, Fuller, J. F.C., A Military History of the Western World, v. II, Da Capo Press Inc., New York, 1955, pp. 64-66.

6. Wilson, pp. 485-487, IBID, Fuller, Wedgwood, C.V., The Thirty Years War, Penguin Books, London, 193, pp. 268-278.

7. Wedgwood, pp. 283-286, Wilson, pp. 501-506.

8. IBID.

9. Wilson, pp. 507-508, Fuller, pp. 68-69.

10. Wilson, pp. 506-508.

11. Wilson, pp. 507-511, Fuller, pp. 69-71, Wedgwood, pp. 287-291.

12. Wilson, pp. 512-519, Wedgwood, pp. 296-302.

13. Wilson, pp. 510-511.

14. Dupuy, Trevor N., The Military Life of Gustavus Adolphus, Scholastic Library Pub., New York, 1969, p. 147.

15. Wilson, pp. 507-511.

16. Wedgwood, pp. 289-291, Parker, Geoffrey, The Thirty Years War, Second Edition, Routledge, New York, 1997, pp. 117-118, also same author, Europe in Crisis, Fontana Books, London, 1979, p. 228. It is interesting to report that although Parker 1997, although reporting the battle has indecisive in the text has a map, (after p. 202 map 3 of the war) which lists the battle has a Swedish victory. Polisensky, J. V., The Thirty Years, New English Library, London, 1970, p. 212.

17. Fuller, pp. 69-70.

18. Dupuy & Dupuy, pp. 538-539.

19. Dodge, p. 384.

20. Parker, 1997, p. 117.

21, Wedgwood, pp. 287-288.

22. Dupuy & Dupuy, p. 539, Fuller p. 71.

23. Wilson, pp. 507-511.

24. Fuller, p. 71. Fuller’s account of the battle is very brief pp. 68-71.

25. Dodge, p. 396-397.

26. Dupuy & Dupuy, p. 539.

27. Parker, 1997, p. 118.

28. Fuller, p. 71.

29. Dodge, p. 396.

30. IBID.

31. IBID. p. 397.

32. Parker, 1997, pp. 123-125.

33. Dupuy & Dupuy, pp. 522-524.

34. See Wilson, pp. 492-511.

35. Dodge, p. 397.

36, Parker, 1997, Plates 9-15, pp. 99-100, 112, Wilson, pp. 475-476, 511.

37. Wedgwood, pp. 291-295.

38. IBID, p. 295.

Pierre Cloutier