Tuesday, June 28, 2016

Friday, May 23, 2014

Monday, July 01, 2013

Wednesday, May 01, 2013

|

| Jean Calvin |

Saturday, February 09, 2013

|

| Book Cover |

Saturday, March 13, 2010

In fact defenestration in my experience, with one exception,2 I’ve only seen it used to describe two separate events and no others. In fact it is like this word was only invented to describe those events and not to describe any other event involving throwing someone out a window. The two examples occurred in the same city and in both cases marked the start of some rather brutal, long wars. I am referring to the First, (1419 C.E.) and Second (1618 C.E.) Defenestrations of Prague.

The Second Defenestration of Prague was in deliberate imitation of the First Defenestration of Prague and was the event that marked the start of the interminable and quite horrible Thirty Years War. I may discuss it at another time.3 The First Defenestration marked the start of another long war that is not well known in the English speaking world; the Hussite Wars. A long, very bloody, precursor to both the Protestant Reformation and the ghastly religious wars that followed.4

Some other time I will discuss the Hussite Wars. Here I will go into a bit of the background and the actual events of First Defenestration of Prague.

The setting for these events is what today we call the Czech Republic. In those days it was a Kingdom with 5 parts. The kingdom of Bohemia, the Margravate of Moravia, Silesia and Upper and Lower Lusatia.5 All of those lands were considered the Lands of the Bohemian crown. Furthermore they were ruled in 1419 by the family of the House of Luxembourg in this case by King Wenceslas IV. Now Wenceslas IV was a son of Charles IV who was not just King of Bohemia but also King of Germany and hence Emperor. (Reign 1346-1378 C.E.) He was also a strong monarch and an incredibly successful one. Unfortunately he decided upon his death that his various holdings would be divided among his various sons and relatives the result was disaster.6

German Emperor

The reason that conflict was simmering was an escalating religious crisis. Bohemia was probably the area in Western Europe that had the biggest and most intense concentration of land in the hands of the Church. In 1410 this amounted to c. ½ of the land.10 Much of it in the hands of various orders like the Dominicans and Franciscans, who also commanded immense wealth in coin, jewellery, bullion and were heavily involved in trade and commerce. This wealth was deeply resented by large sections of the population that felt pressured by Church wealth and power and felt that Church possession of so much wealth curtailed their own economic opportunities. Of course there was also the desire to seize Church property, by a resentful Nobility and Peasantry who felt the market for buying agricultural land much reduced by the Church owning so much of it.11

If greed for Church property along with resentment of Clerical power and wealth was one part of the reason for resentment, the other was a long standing religious revival.

Beginning in the mid 14th century Bohemia had been the center of a movement of religious reform and revival centering on the reformation of the Church, by clearing away corruption and incompetence and a reformation of manners of the laity. As the 14th century went on attacks on the corruption and incompetence and greed of the institutional Church increased in frequency and vitriol. Added to this were such events as the Great Schism (1378-1420 C.E.) which divided Western Christianity over who was Pope. Some countries recognizing the Pope in Avignon as Pope and others the Pope in Rome. The resulting struggle was characterized by much brutality and corruption which reduced the prestige of the papacy to a very low level, and served to massively highlight the corruption and worldliness of the Church. The result was a renewed emphasis that the Church needed to be reformed and cleansed of corruption and purified by returning to the standards of the earliest Church. This meant in practical terms divesting the Church of its wealth, getting rid of debauched, corrupt and ignorant clergy and a re-dedication to the strict standards of early Christianity.12

Thus during this time the works of the great English theologian John Wycliffe, (c. 1325-1384 C.E.) with their call for Church reform and the stripping of the Church of its wealth, which was deemed a corrupting influence, was heard in Bohemia. Beginning in the 1390’s Wycliffe’s works were being read and considered in Bohemia.13

Added to this religious stew was the very real, proto-nationalist, resentment by the Czech people against German influence in Bohemia. The longstanding fear that the Germans would eventually destroy the Czech people. The fact that the various religious orders were dominated by Germans along with the much of the state and Church bureaucracy did not help matters. The reform movement was considered both deliberately and incidentally a way of reasserting Czech identity. The fact that the reform movement preached largely in Czech played a role also.14

The great Czech reformer Jan Hus, (c. 1372-1415 C.E.) heavily influenced by Wycliffe, as indicated by his own writings preached in Prague at the Bethlehem chapel, starting in 1402 C.E.) where deliberately the preaching was in Czech. Although he enjoyed the protection of Wenceslas IV and his wife Queen Zofie, Jan Hus was in constant trouble with other church officials and accused of heresy. His sermons, and those of his followers, attacking the Church and calling for both Church and moral reform were however popular along with his call for the Church to be stripped of its wealth. Eventually Hus was forced into exile in southern Bohemia where he passed the time giving popular outdoor sermons and writing his main theological and institutional works.15

Meanwhile the Great Schism was giving rise to in Bohemia and other places to the feeling that the last days were about to come and that the return of Jesus was imminent. This millennial expectations were both strong and popular and were shared to lesser or greater degree by Jan Hus and some of his followers.16

Hus had by this time a lot of enemies in the Church who wanted his voice to be silenced, he also had achieved for himself and his followers a formidable list of Clerical / Noble supporters in Bohemia and Moravia who were on his side.

During this a Church Council (1414-1418 C.E.) was put together, to a large extent by Sigismund, King of Hungary and German Emperor, to try to heal the Great Schism and it meet at Constance on Lake Constance next to modern day Switzerland. It did eventually succeed in healing the Great Schism by getting the 3 (yes three!) then Popes to resign and electing a new one. It also quite un-intently ignited a religious war. Sigismund was prevailed to give a safe conduct to Jan Hus so he could go there to defend his views and call for reform of the Church. There Jan Hus was arrested, tried and burned at the stake for heresy on July 6, 1415. Sigismund’s refusal to carryout his promise of safe conduct and the farcical trial, along with the argument used that promises given to heretics do not have to be kept are all morally repellent to the highest degree.17

With the support of the King and Queen the Supporters of Jan Hus gained control of Church in Bohemia. The result was a continued struggle over the Church as the Council and Sigismund tried to regain control. Sigismund was by this time looking forward to succeeding his childless brother has King of Bohemia and he felt he needed Church support.

The struggle of the reformers took the form of Utraquistism, from a Latin expression meaning in / under both species or kinds. It referred to the practice of giving to the laity communion in the form of both the bread and the wine. In the west this practice had almost completely disappeared by the early 15th century, replaced by simply giving the bread. However the new movement felt that the process of reform back to an earlier, purer form of Christianity required the return to giving wine to the laity. The fact that Eastern Orthodox Christianity had kept the practice also played a role in the adoption of the practice. The result was that the Chalice from which the laity received the wine became the symbol of the movement now called Hussitism from the name of its martyred founder.19

Rage against the council for the death, (actually judicial murder) of Jan Hus played a role and the rage was increased when Jerome of Prague, one of Jan Hus’ colleagues who had gone to Constance to defend Jan Hus was himself burned at the stake on May 30, 1416. C.E.20

The result was that by the end of 1416 C.E., the Hussite movement had captured the Church in Bohemia and there were already murmurs that a Crusade would have to be waged to crush the “Heretics” in Bohemia.21

The next couple of years were a long and rather tedious series of internal struggles and conflicts with the Church trying to by various means to suppress the Hussite movement and the nobility being divided and king Wenceslas IV and his wide Zofie although basically supporting the Hussite cause trying to reign in the radicals. For it was the radicals who began to define the movement.22

By early 1419 pressure from the Church, which included an economic blockade and threats to invade Bohemia in the guise of a Crusade had become very great. Inside Bohemia a wave of religious and revolutionary enthusiasm had spread through out much of the country. By this time radicals called Taborites had established themselves throughout much of southern Bohemia. There was the widespread belief that the last days had come and the second coming was approaching and that the Church of Rome was the Antichrist.23

Terrified by the forces unleashed Wenceslas IV and queen Zofie tried to reign in the Hussites. First Hussite services were restricted in Prague and regular Catholic services were allowed, (after being prohibited in reaction to Jan Hus’ murder). This increased unrest and significant opposition. On July 6th 1419 the king purged the government of the New Town, (part of Prague and a Hussite stronghold) of Hussite supporters and replaced them with anti-Hussites. Several Hussite supporters were arrested. The stage was set for a show down.24

On July 26th 1419 C.E. Jan Zelivsky gave a heated sermon at St Mary’s in the Snow part of which is as follows:

Thus does Jan Zelivsky pour his contempt on the official Church and its supporters and at the end of his sermon lists the miracles that God has performed for his followers:Indeed, dogs in our own time eat the consecrated bread and the holy charity which belong to the poor. It is given in tumblers to sorcerers, to their servants, and to their servants and to his dogs. All those who eat the bread of the sons act against the truth just like dogs who pounce on a bone.26

…Tobias healed of blindness with the gall of a fish, Daniel saved from the den of lions and Jonah from the stomach of a whale. Christ was born of a virgin, water was changed into wine, three young people were raised: the daughter of Jairus, the widow’s son at the town gate and Lazarus from his tomb. Behold, what an abundance of wonders!27

The pro-Hussite council of the Old Town of Prague and various Hussite supporters of the royal court apparently went along with the coup or actively took part in it. Wenceslas IV was enraged and apparently had a stroke. It appears that he came around to accept the fait accompli but on August 16, 1419 he had another stoke and died.30

There was a problem Wenceslas IV’s heir was his brother Sigismund, who was, not surprisingly, considered responsible for the murders of Jan Hus and Jerome of Prague, who had made repeated statements about crushing heresy in Bohemia and whose entire political career indicated that he was not to be trusted given his continual intrigues, to say nothing about his broken promise to Jan Hus, against his brother Wenceslas IV. Unfortunately his undoubted legitimate claim to the Bohemian throne along with the fear of radical Hussitism gave Sigismund a firm foothold in Bohemia. The result was the truly terrible Hussite wars (1419-1434 C.E.) characterized by revolting brutality and no less than 5 Crusades against the Hussites all of which failed. It was a combination of civil war, Crusade, war of national independence on the part of the Czechs, social revolution, dynastic war and pillaging expeditions.31

Concerning some of the people mentioned in this posting; Jan Zelivsky was executed in 1422 in the midst of faction fighting for the control of Prague. Jan Ziska died in 1424 while besieging a fortress.32

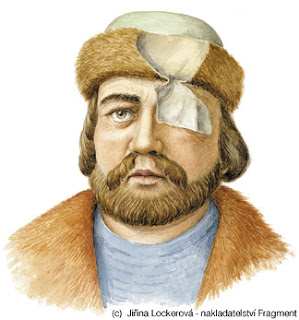

During the war the Czech Hussites created a truly frightening and effective war machine, largely through the genius of the one eyed and later blind Czech general Jan Ziska. Eventually a combination of internal disorder among the Hussite and the failure to crush the Hussites militarily forced the acceptance of a compromise peace. Eventually Sigismund was accepted as king, (in 1436 C.E.), he did not enjoy his kingdom long and died in 1437 C.E., duplicitous to the end.33

Perhaps at another time I will post some more about the Hussite Wars which were in many respects a dress rehearsal for both the Reformation and the Religious wars that followed.

1. Those plastic things at the end of shoe laces.

2. A friend of mine out of the blue used the word in conversation, correctly I might add. Aside from that case I’ve never heard the word in conversation ever.

3. Wedgewoood, C.V., The Thirty Years War, Penguin Books, London, 1938, pp. 73-75. Parker, Geoffrey Editor, The Thirty Years War, Second Edition, Routledge, London, 1997, p. 43, Polisensky, J. V., The Thirty Years War, New English Library, London, 1971, pp. 103-105.

4. Polisensky, pp. 31-32, Parker, p. 7, Cohn, Norman, The Pursuit of the Millennium, Revised Edition, Oxford University Press, 1970, pp. 205-213.

5. Heymann, Frederick G., John Zizka and the Hussite Revolution, Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ, 1955, map p. 2, see also Czech Lands in Wikipedia, Here.

6.Heymann, pp. 38-39, Kaminsky, Howard, The Hussite Revolution, University of California Press, Berkeley CA, 1967, pp. 7-9.

7. Heymann, pp. 23-29.

8. IBID, pp. 36-38, See Wenceslaus, King of the Romans in Wikipedia Here.

9. Heymann, pp. 28-29, 36-38.

10. IBID, p. 39, Cohn p. 205.

11. IBID, pp. 39-43, Kaminsky, pp. 33-34.

12. Kaminsky, pp. 5-55.

13. Kaminsky, pp. 23-35.

14. Kaminsky, pp. 7-22, 35-55, Heymann, pp. 51-60.

15. IBID, Cohn, pp. 205-212. See also Hus, Jan, Letters of Jan Hus, William Whyte and Co. Edinburgh, 1996.

16. IBID, Kaminsky, pp.161-179, 310-360.

17. Heymann, pp. 56-58, Jan Hus, in Wikipedia Here, Lutzow, Count, The Hussite Wars, J.M. Dent and Sons, London, 1914, pp. 1-4.

18. Heymann, pp. 50-51. The number of signatories was 452 and included practically all the higher Czech nobility.

19. Kaminsky, pp. 97-126.

20. Heymann, p. 58, Bernard, Paul P., Jerome of Prague, Austria and the Hussites, Church History, V. 27, No. 1, March, 1958, pp. 3-22.

21. Fudge, Thomas A., Editor, The Crusade against Heretics in Bohemia, 1418-1437, Ashgate, Bodmin Cornwall, 2002, pp. 14-21, Lutzow, pp. 3-9.

22. Heymann, pp. 61-63, Kaminsky, pp. 265-278.

23. Cohn, pp. 205-215, Kaminsky, pp. 310-360.

24. See Footnote 22.

25. Heymann, pp. 62-63, Kaminsky, pp. 271-278.

26. Fudge, p. 23.

27. Fudge, pp. 24-25.

28. Kaminsky, 289-297, Heymann, pp. 63-65.

29. IBID.

30. Heymann, p. 66.

31. See Lutzow, Fudge Introduction, pp. 1-13, and contents, Cohn pp. 221-222 and Heymann and Kaminsky.

33. Heymann, pp. 314-315, 438-440, Lutzow, pp. 127-128, 174-175, Kaminsky, p. 460.

33. Fudge, pp. 341-401, Lutzow, pp. 337-363.

Pierre Cloutier

Thursday, February 25, 2010

Lucrecia Borgia (1480-1519 C.E.) was the daughter of Rodrigo Borgia (1431-1503 C.E.) who reigned as Pope Alexander VI (1492-1503), and his chief mistress Vanozza de Cartaneis.1

The Borgias were a family from Catalonia in modern day Spain called in Catalonia Borja. Rodrigo owed his rise to the fact that his uncle Calixtus III became Pope in 1455 C.E., In 1456 Calixtus III made his nephew Rodrigo a Cardinal. Calixtus died in 1458 C.E. The following decades were characterized by the steady rise to power of Rodrigo who steadily added to his power and influence along with having a string of children by various mistresses. About the year 1475 C.E., Rodrigo met Vanozza and she became his chief mistress and one of his chief advisers until he died. Aside from Lucrecia she also was the mother of several other children by Rodrigo including the brilliant but very sinister Cesare (1475-1507 C.E.) and Juan (1476-1497 C.E.).2

The Borgias during Alexander’s reign acquired a sinister reputation for treachery, ruthlessness and depravity which has stuck with them until the present day. In many respects this is entirely well deserved Rodrigo or Alexander VI, has I will from now on refer to him, acquired the Papal throne in 1492 likely through mass intimidation and bribery. Some modern writers downplay or deny this; given Alexander VI’s subsequent record this seems very unlikely that he didn't engage in massive intimidation and bribery. It appears that that massive quantities of gold and silver flowed to make Alexander VI Pope. One of the stories is that that Alexander VI bribed one Cardinal with four donkey loads of Silver.3

The ruthlessness and corruption that existed all round the family, combined with Alexander’s predilection for high living and luxury resulted in all sorts of rumours floating round about the family. Including incest between Lucrecia and Alexander and / or between Cesare and Lucrecia, along with some inter family murder. Also Lucrecia’s entirely false reputation as a poisoner. Those rumours were false, but given just how corrupt the family could be hardly surprising.4 For example in 1501 there occurred the infamous Banquet or Ballet of the Chestnuts. It was described in a contemporary diary. At this banquet, after dinner, 50 courtesans danced at first clothed and then naked. Chestnuts were then scattered on the floor then diary states:

…which the courtesans, crawling on hands and knees among the candelabra, picked up, while the Pope, Cesare and his sister Lucrecia looked on.5Sex with the courtesans followed with prizes:

In another example of family corruption; Lucrecia’s brother Cesare after failing to successfully poison Lucrecia’s second husband Alfonso cut him to pieces after Alfonso, who well knew who had tried to kill him, tried to kill Cesare.7..for those who could perform the act most often with the courtesans.6

The financial corruption and greed of the family beggars belief in how ruthlessly Alexander sought to enrich himself and establish his family as great potentates in Italy. Unfortunately for Alexander VI and his family he died in 1503 and the family, especially the terrifying Cesare lacked political support without father around. Cesare was rapidly ousted from Italy and died in exile. Lucrecia who had been married to Alfonso d’Estes Duke of Ferrara in 1501 managed to survive the family debacle, eventually becoming a well loved figure in Ferrara.8

However even more than the Banquet of the Chestnuts one incident indicates the almost incredible corruption of the Borgia family. In the summer of 1501 Alexander VI while visiting parts of the Papal state outside of Rome left his daughter Lucrecia in charge of the Vatican. She was given authority to open his mail, see officials and took the place of the Pope at several meetings. Not surprisingly this caused quite a bit of scandal at the time. I suppose it could be compared to what would happen if a president of the United States left the day to day running of the USA to his mistress while on a foreign trip. Some modern day commentators have been absurdly blasé about the whole thing.9

While Alexander was away on this journey, Lucrecia was left in charge of the Vatican. This choice astonished and shocked contemporaries but is itself adequate testimony of Alexander’s completely secular view of Papal administration.10Sometimes people are just a little to complacent about outrageous acts. The bottom line is that this was an act that showed an astounding amount of contempt for the moral reputation of the church and has such was not surprisingly considered incredibly scandalous at the time, because it was!

It is not surprising that in less than 20 years after the death of Alexander VI the severe corruption within the church would really help to engender the Protestant Reformation and produce another serious religious split in Christendom.11

Of her father Pope Alexander VI

1. Lucrezia Borgia, at Wikipedia, Here, Durant, Will, The Renaissance, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1953, pp. 428-433, Mallett, Michael, The Borgias, Paladin, London, 1971, p. 99.

2. Durant, pp. 404-428, Mallett, pp. 60-79.

3. Durant, p. 406, Mallett, pp. 106-110, De Rosa, Peter, Vicars of Christ, Bantam Press, Toronto, 1988, p. 104, Tuchman, Barbara, The March of Folly, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1984, p. 78.

4. Durant, pp. 411-417, Mallett, pp. 11-12, Tuchman, p. 85.

5. Quoted by Tuchman, p. 88. For other brief account of the Banquet of the Chestnuts see Mallett, pp. 205-206, and De Rosa, pp. 106-107.

6. IBID.

7. IBID, Tuchman, Durant, pp. 430-431, De Rosa, p. 108.

8. Mallett, pp. 215-227, 232-241, Durant, pp. 433-440., Tuchman, pp. 88-90.

9. Mallett, p. 162-163, Durant, p. 412.

10. Mallett, p. 162.

11. The first split was between Catholicism and Orthodox which became final in 1054 C.E. See Ostrogorsky, George, History of the Byzantine State, 2nd Edition, Basil Blackwell, Padstow Cornwall, 1968, pp. 336-338. For a short review of how papal corruption help provoke the Protestant Reformation see The Renaissance Popes Provoke the Protestant Secession: 1470-1530, in Tuchman, pp. 51-126.

Pierre Cloutier

Tuesday, December 29, 2009

Things were not so bad as 70+ years ago when C.V. Wedgwood wrote her book on the Thirty Years War because of a almost complete dearth of English accounts.2 It was and remained the the only even remotely comprehensive account in English for quite some time. In fact the book under review may be in fact the account that supersedes it at last. There are are of course other accounts but they are in comparison brief, sketchy and tend to provide great detail on some aspects of the war but none or barely any at all on other aspects.

This account is first of all fairly long with c. 850 pages of text it provides much more detailed coverage of the war especially military events of the last phases of the war than Wedgwood's account. In fact the general tendency is for accounts in most languages to neglect the last 13 years of the war, after France openly declared war on the Habsburgs.

The book has a fairly long section, (265 pages) devoted to giving the background to the conflict, which the author feels was rooted in not just the confessional struggle between Catholics and Protestants, but disputes within the Habsburg family and the debate over the actual powers and prerogatives of the Empire \ Emperors.

The Habsburgs were not simply lords of the lands they controlled they were also Emperors of what was called the Holy Roman Empire. Usually dismissed by modern historians as a collection of independent principalities under the nominal rule of the Habsburg Emperors. The author here of the book under review makes the case that it did have some institutions (like the Reichstag) a system of courts, etc., that functioned with a fair degree of efficiency.

The most telling indication of that efficiency on some level was the peace that existed in much of the Empire. War was basically confined to the peripheries of the empire. This peace had lasted since c. 1552 C.E. The conflict had arisen from the confessional dispute between Catholics and Protestants. Despite the virulent nature of this dispute the compromises worked out then had proven to be successful and the great majority of the Empire had enjoyed 2 generations of peace.

When the crackup happened the results were terrible. Blindly the protagonists blundered into a hellish conflict that that they all seemed incapable of ending.

The Empire in 1618 was not just German it had French, Danish, Czech, Italian speakers also. When the empire plunged into its long night of war it dragged the surrounding countries into it has they sought to take advantage of the internal problems of the Empire. What they generally got was being enmeshed in a costly horrible struggle they could not easily get out of.

The war had a long list of colourful characters such as, Archduchess Isabella of Belgium, Maximilian of Bavaria, Oxenstierna and Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, General Wallenstein, Emperors Ferdinand II and III, Cardinal Richelieu, Count Olivares of Spain. They all got tangled in this interminable war.

In some respects this book as a revisionistic cast. For example it does not engage in the usual writhing about the genius of the Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus, or the usual gasping, awestruck hero worship of the 'Lion of the North'.3 For example going against over a century of conventional opinion the author does not characterize the battle of Lutzen, 1632, during which Gustavus got himself killed, as a great Swedish victory; but correctly describes it has a draw.4 The simple fact is that Gustavus' wars and foreign policy got Sweden involved in several costly wasteful wars that Sweden could ill afford and were well beyond her strength; all in pursuit of grandiose, unrealistic religious and political goals. Only Sweden's ability to plunder Germany for men and money combined with massive French assistance enabled Sweden to carry on at all. Sweden as a great power was an illusion built on bluff and the weakness of her neighbours. Gustavus saddled Sweden with this status that cost Sweden much until the illusion was finally burst at Poltava in 1709.

Within a few years of Sweden entering the war more than two thirds of the soldiers, and usually more than three quarters were non Swedes \ Finns. In fact most were Germans, including the officers. Most of cost of paying for the war was borne by exploiting and pillaging Germany. Even so Sweden was impoverished and suffered heavy losses during the war.5

Aside from the above mentioned fairly detailed descriptions of the last c. 13 years (1635-1648) of the war which are usually covered briefly this book provides fairly detailed coverage of the policies and plans of perhaps the most important personality of the war and probably its most important figure; the french politician, statesman Cardinal Richelieu. Generally known today through bad film adaptions of Alexandre Dumas Musketeers tales as a cardboard villain he was in fact a stunningly capable, cold-blooded practitioner of realistic policy.

It was mainly through Cardinal Richelieu that the forces keeping the anti-Habsburg coalition kept going. In most respects almost from the beginning the struggle was between Bourbon and Habsburg for hegemony in Europe. Cardinal Richelieu was terrified at the prospect of the establishment of effective Habsburg rule over the Empire which would lead in his estimation to Habsburg hegemony in Europe.

In this respect when in 1635 open war between Bourbon and Habsburg finally started, only then did the real point of dispute of the war come into the open. It is of interest that only the at first covert and then open intervention of Catholic France prevent the Protestant powers from defeat. But then Cardinal Richelieu was never one to allow religion to interfere with what he perceived to be the true interests of France.

The confessional aspects of the struggle were in many respects mere window dressing; although useful for propaganda. Although the war ended with significant Protestant retreat in much of central Europe; it also froze the confessional divide and lead to the re-establishment of of toleration in much of the Empire with the exception of most of the Habsburg hereditary lands were Catholicism was imposed by force.

It is of interest that by 1635 the Habsburgs had largely given up their efforts to impose a one sided confessional and constitutional solution on the Empire. That was the year of the Peace of Prague. It was the interference of foreign powers France, Sweden and Spain that prolonged the war for another 13 years. In the end the peace finally agreed to (Wesphalia 1648) was not much different from Prague although France and Sweden got more and the Emperor less.6

In fact one of the myths that this book dispels is the story that the Empire was made impotent and the Emperors weak. In fact this is a exaggeration and the Habsburgs quickly regained a great deal of influence very quickly.7 In fact the idea that the Habsburgs experienced a comprehensive defeat is a myth. The Habsburgs lost but they were not crushed and the peace was in many respects a compromise by enemies who were mutually exhausted.

In the section describing the aftermath, Wilson rightly questions the myth of the all destructive fury of the war. The nonsense about two thirds dying etc. He points out how some areas were devastated repeatedly and other areas escaped u nharmed. How one area might be ravaged and then escape any more devastation and so forth. Still the picture is sombre after all it appears that over all the population of the Empire fell by 15-20%. Some areas suffered much worst like Bohemia and Moravia. That is a frightening picture and much worst than the decline during the Second World War.8

People died not so much of direct violence, although that killed a large number, but of disease, plague and hunger. The devastation, anarchy produced by the fighting, the breakdown of order produced mass death.9 In fact in some places peasant guerrillas emerged that attacked the soldiers of both sides in a desperate effort to achieve some security.10

The negotiations in Westphalia took years and the paroxysms throughout the Empire of joy that greeted the signing of the peace in 1648 are some of the most extraordinary events in European history. Even more remarkable was the rapid economic \ demographic recovery after the war and a long period of peace in most of the Empire.11

The war left an indelible cultural memory of horror in Central Europe which as inspired works of art to this day.12 Only in the first half of the 20th century did horrors on the scale of the Thirty Years War return to Europe.For a glimpse into a war all too few English speaking people know about I heartily recommend this book.

1. Wilson, Peter H., The Thirty Years War, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MASS., 2009.

2. Wedgwood, C. V., The Thirty Years War, NYRB Classics, New York, 2005, (original pub. 1938).

3. Wilson, pp. 459-511.

4. IBID, pp. 510-511.

5. IBID, pp. 791, gives c. 110,000 Swedish \ Finnish dead during the war. For a country of c. 1.2 million this is quite terrible. Wilson, same page, gives a figure of at least 400,000 for Germans and others who died in Swedish service.

6. IBID, pp. 758-773.

7. IBID, pp. 773-776.

8. IBID, pp. 786-795. Bohemia's population declined from 1,400,000 to 1,000,000, a decline of 29%, Moravia's population declined from 650,000 to 450,000, a decline of 31%. From Wilson, p. 788.

9. IBID.

10. IBID, pp. 532-534.

11. IBID. pp, 805-806.

12. For Example Brecht's Mother Courage and Her Children.

Pierre Cloutier

Tuesday, August 25, 2009

Now Julius II was a formidable statesman and even led troops into battle he was also a great builder and a patron of Michelangelo, (the Sistine Chapel and other projects, including the rebuilding of St. Peters). However he was also a relentlessly earthly man obsessed with money and power who put off and fatally undermined any effort to reform the Church.1

Erasmus was a reformer keenly interested in reforming the Church of abuses and eliminating corruption and Julius was an outstanding example of corruption within the Church.2 So that a few years later, (1517/18), after Julius’ death this work appeared.

Erasmus never stated bluntly that he wrote this work although he also never denied authorship. It is in fact rather revealing that he in fact said that those who made this piece public were more to blame than the actual author. Which is rather significant. Other people were given credit for this piece but the opinion of most of Erasmus’ contemporaries and later scholarship is that Erasmus wrote it.3

The piece states with Julius banging on to heaven’s gate accompanied by his Genius or guiding spirit. St. Peter comes to see what is the commotion is all about.

Peter is not too impressed with Julius:

…I see that all your equipment, key, crown, and robe, bears the marks of that villainous huckster and impostor, who had my name but not my nature, Simon, whom I humbled long ago with the aid of Christ.

Julius Stop this nonsense, if you know what’s good for you; for your information, I am Julius, the famous Ligurian; and unless you’ve completely forgotten your alphabet, I’m sure you recognize those two letters, P.M.

Peter I suppose they stand for Pestis Maxima.

Genius Ha ha ha! Our soothsayer has hit the nail on the head!

Julius Of course not! Pontifex Maximus.4

…you’re all belches and that you stink of boozing and hangovers and you look as if you’ve just thrown up. Your whole body is in such a state that I should guess that it’s been wasted, withered and rotted less by old age and illness than by drink.

Genius A fine portrait: Julius to the life!5

Peter Well. Did you win many souls for Christ by the saintliness of your life?

Genius He sent a good many to Tartarus.

Peter Were you famous for your miracles?

Julius This is old-fashioned stuff.

Peter Did you pray simply and regularly?

Julius What’s he jabbering about? Lot of nonsense!6

…today there is not one Christian king whom I have not incited to battle, after breaking, tearing, and shattering all the treaties by which they had painstakingly come to agreement among themselves;…7

Julius Simply that, under his administration, our treasury got only a miserable few thousand out of the enormous sums he collected from his citizens. But in any case, his deposition fitted in well with the plans I was making at the time. So the French, and some others who were intimidated by my thunderbolt, set to work with a will; Bentivoglio was overthrown, and I installed cardinals and bishops to run the city so that the whole of its revenue would be at the service of the Roman church.8

Peter Were they true or false?

Julius What’s the difference? It’s sacrilege even to whisper anything about the Roman pontiff, except in praise of him.9

They said that all our doings were tainted by a shameful obsession with money, by monstrous and unspeakable vices, sorcery, sacrilege, murder, and graft and simony. They said that I myself was a simoniac, a drunkard, and a lecher, obsessed with the things of this world, an absolute disaster for the Christian commonwealth, and in every way unworthy to occupy my position.10

Was what they said true?

Julius Indeed it was.11

Peter also asks:

But were you as bad as they claimed?

Julius Does it matter? I was supreme pontiff. Suppose I were more vicious than the Cercopes, stupider than Morychus, more ignorant than a log, fouler than Lerna: any holder of this key of power must be venerated as the vicar of Christ and looked on as most holy.12

In fact, he cannot be deprived of his jurisdiction for any crime at all.

Peter Not for murder?

Julius Not for parricide.

Peter Not for fornication?

Julius Such language! No, not even for incest.

Peter Not for unholy simony?

Julius Not even for hundreds of simoniacal acts.

Peter Not for sorcery?

Julius Not even for sacrilege.

Peter Not for blasphemy?

Julius No, I tell you.

Peter Not for all these combined in one monstrous creature?

Julius Look, you can run through a thousand other crimes if you like, all more hideous than these: the Roman pontiff still cannot be deposed for them.13

I’d be quite willing to welcome Indians, Africans, Ethiopians, Greeks, so long as they paid up and acknowledged our supremacy by sending in their taxes.14

Julius Ah, now you’re coming to it: listen. The church, once poor and staving, is now enriched with every possible ornament.

Peter What ornaments? Warm faith?

Julius You’re talking nonsense again.

Peter Sacred learning?

Julius You don’t give up, do you?

Peter Contempt for the world?

Julius Allow me to explain. I’m talking about real ornaments, not mere words like those.

Peter What then?

Julius Royal palaces, the most handsome horses and mules, hordes servants, well trained troops, dainty courtiers…15

That I was looking at a tyrant worse than any in the world, the enemy of Christ, the bane of the church.16

O worthy vicar of Christ who gave himself to save all men, while you have engineered the ruin of the whole world to save your own pestilent head!

Julius You’re only saying that because you begrudge us our glory, realizing how insignificant your pontificate was compared to ours.17

I’ve never heard such things.18

But now I see the opposite of this: the man who wishes to be thought the closest Christ, even his equal, is involved with all the most sordid things, money, power, armies, wars, treaties, not to mention vices. And yet, although you are furthest from Christ, you use the name of Christ to bolster your pride; you act like an earthy tyrant in the name of him who despised the kingdoms of earth, and you claim the honour due Christ although you are truly Christ’s enemy.19

The last person I’d let in is a pestilent fellow like you. In any case, we’re excommunicated, according to you. But would you like some friendly advice? You have a band of energetic followers, an enormous fortune, and you, yourself are a great architect; build some new paradise for yourself, but fortify it well to prevent evil demons capturing it.20Julius true to form rejects the advice and tells Peter that he will wait a few months and storm heaven.

Peter as a few words with Julius' Genius who tells him the Julius leads and he merely follows. The dialogue then ends.

This vicious, but funny dialogue illustrates quite well the problems with the Papacy that helped lead to the Protestant Reformation and in also the Counter Reformation. It is also a fun read.

1. MacCulloch, Diarmaid, Reformation, Penguin Books, London, 2003, pp. 41-42, 87-88, Tuchman, Barbara W., The March of Folly, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1984, pp. 91-103.

2. IBID.

3. Erasmus, The Erasmus Reader, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1990, p. 216. Julius Excluded from Heaven is on pp. 216-238.

4. IBID. p. 217.

5. IBID. pp. 218-219.

6. IBID. p. 230.

7. IBID. p. 232.

8. IBID. p. 226.

9. IBID. p. 227.

10. IBID. p. 228.

11. IBID.

12. IBID.

13. IBID. pp. 229-230.

14. IBID. p. 231.

15. IBID. p. 232.

16. IBID. p. 233.

17. IBID. p. 234.

18. IBID. p. 235.

19. IBID. p. 237.

20. IBID. p. 238.

Pierre Cloutier

Tuesday, July 28, 2009

There is a tendency among some historians to try to justify brutal , authoritarian rule on the grounds that it is necessary to preserve order.

Dr. Elton seems to be totally unaware of the damage done to the fabric of society when governments positively encourage denunciations of neighbours by neighbours, thus opening up a Pandora's box of local malice and slander. No one who has read a little about life in occupied Europe under the Nazi, or has seen the movie Le Chagrin et La Pitie, [A documentary about life in France during the Nazi Occupation] could share the satisfaction of Dr. Elton as he triumphantly concludes that his hero encouraged private delation rather than relying on a system of paid informers.6