Frederick II and the Outbreak of the Seven Years War.

Frederick is called the “Great” because he was successful at war, or should I say thought to be successful at war, and because he succeeded in conquering territory and making Prussia one of the great powers of Europe. Basically he is a “Great” man because he succeeded. The actual manner by which he achieved his success and the cost of his success for others is as per usual in these things downgraded / ignored. This worship of military success leads to the idea that Frederick was “Great” in all sorts of things and a fawning, hero worship that writhes in ecstasy at his “glorious” victories and genuflects at his shrine.3

One can go into the rather puzzling question about how a King who massively strengthened the militaristic nature of the Prussian state, and its Police State apparatus and in effect completed the process of turning the Prussian state from a State with an army to an Army with a State could for a moment fool anyone into thinking he was an “Enlightened” monarch. But then military success does tend to dazzle. But then Frederick easily put on “enlightened” airs and dazzled the literati of his day with a lot of words and pretty speeches about “enlightened” values while increasing the subordination of society to the state and its army. That Frederick was also incredibly vain, arrogant and loath to take responsibility for things if things went wrong, (blaming other people was a fine if childish art with Frederick). That Frederick was also in many respects a reckless diplomat and frequently engaged in political and other acts of fairly dubious morality is often forgotten.4

For example when Maria-Theresa inherited the Austrian throne in 1740, Austria had been going through a long term period of decline and it was only with difficulty that Maria-Theresa’s father Charles VI was able to arrange for the myriad domains of the house of Habsburg to accept the succession of his daughter Maria-Theresa; who became the only female ruler of the house of Habsburg. This so-called Pragmatic Sanction was then accepted by the various major powers of Europe through the tireless diplomacy of Charles VI who was anxious to avoid a diplomatic crisis upon the accession of his daughter. Also there was his concern that the other powers would seek to take advantage of Maria-Theresa’s accession to attack Austria and attempt to partition the empire between them.

Despite the anticipation of crisis Maria-Theresa succeeded her father in 1740 and at first it looked as if the various powers would accept the Pragmatic Sanction and let Maria-Theresa reign in peace. Frederick who had recently come to the throne of Prussia decided that given that so many powers were just waiting to attack Austria and carve her up that he would start the whole process, this was after he had signed a treaty saying he would respect the Pragmatic Sanction.5

The result was the war of Austrian Succession an interminable 8 year war during which Prussia was able to wrest the province of Silesia from Austria. Despite the serious decay of Austrian institutions and military during Charles VI’s reign, (Charles was a good diplomat but not a good administrator and Austria fell behind and looked like ripe pickings for the other powers), Maria-Theresa, who had not been educated or trained in any fashion to rule proved to be a very capable if not great ruler, and despite her almost total lack of experience rose to the challenge.6

Frederick went to war, made peace and unmade alliances almost at will with little regard to any moral imperatives or even his word. Frederick blithely betrayed his allies twice by making separate peace treaties with Austria and broke his agreements with Austria with equal facility. In the end though Frederick ended up with Silesia a province that increased the population of Prussia by more than 50% and a even larger increase in wealth. In fact Prussia’s pretensions of being a great power were dependent on possession of Silesia.7

Frederick had inherited from his father, Frederick William I, (a man whose behavior indicated a psychopathic personality), an excellent, large standing army that by means of the most draconian exploitation of the country he was able to extract from his fairly small country. Frederick had great ambitions and from the first wanted to take Austrian lands to further those ambitions.8

Austria was able fight off this attempt to partition her. Aside from Silesia Austria lost very little territory. But the war convinced Maria-Theresa of the urgent need to reform and revitalize the state. As an “enlightened” monarch Maria-Theresa easily puts Frederick in the shade and unlike him the challenges that she faced and difficulties she had to overcome were quite significantly greater. Further unlike Frederick Maria-Theresa had real moral scruples which did affect her behavior and policies. The idea of subordinating the state to the army was anathema to her. If Maria-Theresa had inherited a ramshackle state she was with remarkable skill able to hold the great majority of it together despite everything.9

Despite the ohhs and awws of the literati Frederick’s double dealing in this period had left a bad taste in the mouths of many including that of Frederick’s allies, especially France. Although many were dazzled by Frederick’s military victories, Frederick had a serious enemy in Maria-Theresa, who wanted Silesia back and it would have been prudent for Frederick to make every effort to remain an ally of France in order to hold Austria back from a war of revenge. Well to put it bluntly Frederick muffed it.10

The story of the long diplomatic intrigues that eventually resulted in the alliance of Russia, France and Austria against Prussia belongs in another essay suffice to say Frederick proved a clumsy and basically inept diplomat at the time. The fact that he was suspected of having further massive territorial designs especially on the lands of the Austrian monarchy, which were in fact true, increased the determination of Maria-Theresa to cut him down to size. Prussian schemes to annex parts of Poland increased Russian anxieties and France was utterly infuriated by Frederick’s behavior during the war of Austrian Succession and felt it could not trust him at all.11

In the end France, reversing a policy of long standing (centuries) signed an alliance with Austria and Russia joined in. Now this alliance, which was only formalized after Frederick attacked Saxony, was defensive in nature and frankly neither France nor Russia was really all that interested in a war to gain Silesia back for Austria, but all three powers were determined to contain Prussia, and its King who they viewed as a loose cannon liable to go off in any direction.12

Frederick muffed it again. In 1756 he invaded Saxony and then Austria deliberately starting a war with France, Austria and Russia.

Faced with a circle of enemies Frederick decided to attack. Frederick’s defenders have from that day to this have defended his action as a preventive strike designed to anticipate his enemies and hence a move a great boldness.

Further Frederick is congratulated for trying to break up his enemies by attacking first and trying to drive Austria out of the alliance and thus breaking up the coalition against him. This is of course to take Frederick’s self serving apologia at face value. What is forgotten is that Austria, Russia and France had a defensive alliance not an offensive one. Neither France nor Russia were terribly eager to fight a war solely for Austria to get back Silesia. Further Frederick attacked Saxony an ally of Austria, not Austria. What is forgotten is also that Frederick did indeed want to defeat Saxony and Austria quickly, and then impose on both a peace that would satisfy his long standing desire for much more territory from both of them. In other words Frederick attacked Austria and Saxony in order to extract from both has much territory as possible not just to break up a coalition against him. He also had plans to impose a heavy indemnity on both. What happened is that both Russia and France pursuant to their alliance with Austria declared war on Prussia. Thus Frederick had, with great efficiency, created a powerful coalition against himself.13

Having thus set himself up for failure and being crushed by a much more powerful coalition, Frederick would spend most of the next seven years desperately trying to save himself from the predicament he had so expertly put himself in. Needless to say the Frederick gawkers would spend centuries afterwards writhing in ecstasy at Frederick’s “greatness” in holding off a much more powerful coalition and repeating Frederick’s self serving apologia that the war was inevitable and that he was thus justified in attacking first, carefully avoiding the fact that the so-called inevitable attack was NOT inevitable. Further that Frederick’s behavior was in effect a self fulfilling prophecy and that Frederick had very ambitious territorial ambitions, against Austria, Saxony and Poland, which he was most anxious to satisfy. In other words Frederick's attack was an act of aggression designed to seize territory, at least in part.14

It takes real incompetence to put your head in the noose the way Frederick did. Frederick in the end was only saved one of the most bizarre strokes of good fortune ever, for which he could take no responsibility. Another time I will go into that stroke of fortune. Meanwhile the people of Prussia, Saxony, Austria, Russia, Germany, and France would pay for Frederick’s incompetent diplomacy, lack of scruple and ambition in spades.15

1. The number of suck-up biographies of Frederick the “Great” is legion perhaps the most stomach turning, at least in English, is Carlyle, Thomas, History of Frederick the Great, Six Volumes, Robson and Son, London, 1858-1865. Google Books, Here, see also Fuller, J. F. C., A Military History of the Western World, v. 2, DaCapo, New York, 1955, pp. 192-215.

2. Szabo, Franz A., The Seven Years War in Europe 1756-1763, Pearson, Longman, London, 2008.

3. See Carlyle above and Duffy, Christopher, Frederick the Great: A Military Life, Routledge, London, 1985 for many examples.

4. See Duffy, pp. 195-196, Szabo, pp. 87-88, 238-240, 253-255, Williams, E. N., The Ancien Regime in Europe, Penguin Books, London, 1970, pp. 372-398, Waite, Robert, G. L., The Psychopathic God, Signet, New York, 1977, pp. 306-311, Ogg, David, Europe of the Ancien Regime 1715-1783, Harper Torchbooks, New York, 1965, pp. 212-217, Hufton, Olwen, Europe: Privilege and Protest: 1730-1789, Fontana Books, London, 1980, pp. 191-219.

5. IBID, Waite, Williams, pp. 430-432, Ogg, pp. 124-127.161-168.

6. No really good biography of Maria-Theresa exists in English, but see Williams, pp. 435-459, Ogg, 206-211, Hufton, pp. 160-73.

7. Hufton, pp. 191, 206.

8. See Williams, pp. 335-351, Waite, 306-307, Williams, 376-378, Hufton, 205-206, Ogg, 161-168.

9. Ogg, pp. 210-211, Williams, 435-459, Hufton, 160-173.

10. Williams, pp. 437-438, Ogg, pp. 138-143, Duffy, pp. 82-85, Szabo, pp. 8-18.

11. IBID.

12. IBID.

13. IBID, and Szabo, pp. 10, 37, 82.

14. IBID.

15. Duffy, pp. 242, 244, Hufton, pp. 211-212. Prussia for example lost 400-500 thousand people.

Pierre Cloutier

Mesopotamian Seal

Mesopotamian Seal

Head of Akkadian King

Head of Akkadian King

Map illustrating Boundary created by Treaty of Wichale

Map illustrating Boundary created by Treaty of Wichale

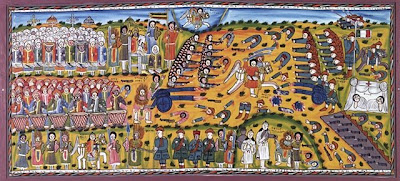

Battle of Adowa - Ethiopian Painting

Battle of Adowa - Ethiopian Painting

Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson