|

| Humphrey: Duke of Gloucester |

Wednesday, February 06, 2013

Sunday, December 12, 2010

This is the hole through which the English entered France.2

Charles, by the grace of God, king of France, to all our bailiffs, provosts, seneschals, and to all the principal of our officers of justice, or to their lieutenants, greeting. Be it known, that we have this day concluded a perpetual peace, in our town of Troyes, with our very dear and well-beloved son Henry king of England, heir and regent of France, in our name and in his own, in consequence of his marriage, with our well-beloved daughter Catherine, and by other articles in the treaty concluded between us, for the welfare and good of our subjects, and for the security of the realm; so that henceforward our subjects, and those of our said son, may traffic and have a mutual intercourse with each other, as well on this as on the other side of the sea.1. It has been agreed that our said son king Henry, shall henceforth honour us as his father, and our consort the queen as his mother, but shall not by any means prevent us from the peaceable enjoyment of our crown during our life.2. Our said son king Henry, engages that he will not interfere with the rights and royalties of our crown so long as we may live, nor with the revenues, but that they may be applied as before to the support of our government and the charges of the state; and that our consort the queen shall enjoy her state and dignity of queen, according to the custom of the realm, with the unmolested enjoyment of the revenues and domains attached to it.3. It is agreed that our said daughter Catherine shall have such dower paid her from the revenues of England as English queens have hitherto enjoyed, namely, sixty thousand crowns, two of which are of the value of an English noble.4. It is agreed that our said son king Henry, shall, by every means in his power, without transgressing the laws he has sworn to maintain, and the customs of England, assure to our said daughter Catherine the punctual payment of the aforesaid dower of sixty thousand crowns from the moment of his decease.5. It is agreed, that should it happen that our said daughter survive our said son, king Henry, she shall receive, as her dower from the kingdom of France, the sum of forty thousand francs yearly; and this sum shall be settled on the lands and lordships which were formerly held in dower by our very dear and well beloved the lady Blanche, consort to king Philip of France, of happy memory, our very redoubted lord and great grandfather.6. It is agreed that immediately on our decease, and from thenceforward, our crown and kingdom of France, with all its rights and appurtenances, shall devolve for ever to our said son king Henry, and to his heirs.(6. After our death [Charles VI], and from that time forward, the crown and kingdom of France, with all their rights and appurtenances, shall be vested permanently in our son [son-in law], King Henry [of England], and his heirs.)7. Because we are for the greater part of our time personally prevented from attending to the affairs and government of our realm with the attention they deserve, the government of our kingdom shall in future be conducted by our said son king Henry, during our life, calling to his assistance and council such of our nobles as have remained obedient to us, and who have the welfare of the realm and the public good at heart, so that affairs may be conducted to the honour of God, of ourself and consort, and to the general welfare and security of the kingdom ; and that tranquillity may be restored to it, and justice and equity take place everywhere by the aid of the great lords, barons, and nobles of the realm.

(7.....The power and authority to govern and to control the public affairs of the said kingdom shall, during our lifetime, be vested in our son, King Henry, with the advice of the nobles and wise men who are obedient to us, and who have consideration for the advancement and honor of the said kingdom....)8. Our said son shall, to the utmost of his power, support the courts of parliament of France, in all parts that are subject to us, and their authority shall be upheld and maintained with rigour from this time forward.9. Our said son shall exert himself to defend and maintain each of our nobility, cities, towns and municipalities in all their accustomed rights, franchises, and privileges, so that they be not individually nor collectively molested in them.10. Our said son shall labour diligently, that justice be administered throughout the realm, according to the accustomed usages, without exception of anyone, and will bodily defend and guard all our subjects from all violence and oppression whatever.11. It is agreed that our said son king Henry shall appoint to all vacant places, as well in the court of parliament as in the bailiwicks, seneschalships, provostships, and to all other offices within our realm, observing that he do nominate fit and proper persons for such offices, fully acquainted with the laws and customs of the country, so that tranquility may be preserved, and the kingdom flourish.12. Our said son will most diligently exert himself to reduce to our obedience all cities, towns, castles and forts, now in rebellion against us, and of the party commonly called Dauphinois or Armagnac.13. For the more secure observance of these articles, and the more effectually to enable our said son king Henry to carry them into execution, it is agreed that all the great lords, as well spiritual as temporal, all the cities, towns, and municipalities within our realm, and under our obedience, shall each of them take the following oaths: They shall swear obedience and loyalty to our said son king Henry, in so much as we have invested him with the full power of governing our kingdom of France in conjunction with such counsel of able men as he may appoint. They will likewise swear to observe punctually whatever we, in conjunction with our consort the queen, our said son king Henry, and the council, may ordain. The cities, towns, and municipalities, will also swear to obey and diligently follow whatever orders may particularly affect them.14. Instantly on our decease the whole of the subjects of our kingdom shall swear to become liegemen and vassals to our said son king Henry, and obey him as the true king of France, and, without any opposition or dispute, shall receive him as such, and never pay obedience to any other as king or regent of France but to our said son king Henry, unless our said son should lose life or limb, or be attacked by a mortal disease, or suffer diminution in person, state, honour, or goods. But should they know of any evil designs plotted against him, they will counteract them to the utmost of their power, and give him information thereof by letters or messages.

15. It is agreed that whatever conquests our said son may make from our disobedient subjects shall belong to us, and their profits shall be applied to our use; but should any of these conquests appertain to any noble who at this moment is obedient to us, and who shall swear that he will faithfully defend them, they shall be punctually restored to him as to the lawful owner.16. It is agreed that all ecclesiastics within the duchy of Normandy and the realm of France, obedient to us, to our said son, and attached to the party of the duke of Burgundy, who shall swear faithfully to keep and observe all the articles of this treaty, shall peaceably enjoy their said benefices in the duchy of Normandy, and in all other parts of our realm.17. All universities, colleges, churches, and monasteries, within the duchy of Normandy or elsewhere, subject to us, and in time to come to our said son king Henry, shall freely enjoy all rights and privileges claimed by them, saving the rights of the crown and of individuals.18. Whenever the crown of France shall devolve by our decease on our said son king Henry, the duchy of Normandy, and all the other conquests which he may have made within the kingdom of France, shall thenceforward remain under the obedience and jurisdiction of the monarchy of France.19. It is agreed that our said son king Henry, on coming to the throne of France, will make ample compensation to all of the Burgundian party who may have been deprived of their inheritances by his conquest of the duchy of Normandy, from lands to be conquered from our rebellious subjects, without any diminution from the crown of France. Should the estates of such not have been disposed of by our said son, he will instantly have the same restored to their proper owners.

20. During our life all ordinances, edicts, pardons and privileges, must be written in our name, and signed with our seal; but as cases may arise which no human wisdom can foresee, it may be proper that our said son king Henry should write letters in his own name, and in such cases it shall be lawful for him so to do, for the better security of our person, and the maintaining good government ; and he will then command and order in our name, and in his own, as regent of the realm, according as the exigency of the occasion may require.

21. During our life our said son king Henry will neither sign nor style himself king of France, but will most punctually abstain there from so long as we shall live.22. It is agreed that during our life we shall write, call and style our said son king Henry as follows: Our very dear son Henry, king of England, heir to France and in the Latin tongue, Noster praecharissimus filius Henricus rex Anglias heeres Franciae.(22. It is agreed that during our life-time we shall designate our son, King Henry, in the French Language in this fashion, Nortre tres cher fils Henri, roi d’angleterre, heritier de France; and in the Latin Language Noster praecarissimus filius Henricus, rex Angliae, heres Francae.)23. Our said son king Henry will not impose any taxes on our subjects, except for a sufficient cause, or for the general good of the kingdom, and according to the approved laws and usages observed in such cases.24. That perfect concord and peace may be preserved between the two kingdoms of France and England henceforward, and that obstacles tending to a breach thereof (which God forbid) may be obviated, it is agreed that our said son king Henry, with the aid of the three estates of each kingdom, shall labour most earnestly to devise the surest means to prevent this treaty from being infringed: that on our said son succeeding to the throne of France, the two crowns shall ever after remain united in the same person, that is to say, in the person of our said son, and at his decease, in the persons of those of his heirs who shall successively follow him: that from the time our said son shall become king of France the two kingdoms shall no longer be divided, but the sovereign of the one shall be the sovereign of the other, and to each kingdom its own separate laws and customs shall be most religiously preserved.(24.....[It is agreed] that the two kingdoms shall be governed from the time that our said son, or any of his heirs shall assume the crown, not divided between different kings at the same time, but under one person who shall be king and sovereign lord of both kingdoms; observing all pledges and all other things to each kingdom its rights, liberties or customs, usages and laws, not submitting in any manner one kingdom to the other.)25. Thenceforward, therefore, all hatreds and rancour that may have existed between the two nations of England and France shall be put an end to, and mutual love and friendship subsist in their stead: they shall enjoy perpetual peace, and assist each other against all who may any way attempt to injure either of them. They will carry on a friendly intercourse and commerce, paying the accustomed duties that each kingdom has established.26. When the confederates and allies of the kingdoms of France and of England shall have had due notice of this treaty of peace, and within eight months after shall have signified their intentions of adhering to it, they shall be comprehended and accounted as the allies of both kingdoms, saving always the rights of our crown and of that of our said son king Henry, and without any hindrance to our subjects from seeking that redress they may think just from any individuals of these our allies.27. It is agreed that our said son king Henry, with the advice of our well-beloved Philip duke of Burgundy, and others of the nobles of our realm, assembled for this purpose, shall provide for the security of our person conformably to our royal estate and dignity, in such wise that it may redound to the glory of God, to our honour, and to that of the kingdom of France and our subjects; and that all persons employed in our personal service, noble or otherwise, and in any charge concerning the crown, shall be Frenchmen born in France, and in such places where the French language is spoken, and of good and decent character, loyal subjects, and well suited to the offices they shall be appointed to.28. We will that our residence be in some of the principal places within our dominions, and not elsewhere.29. Considering the horrible and enormous crimes that have been perpetrated in our kingdom of France, by Charles, calling himself dauphin of Vienne, it is agreed that neither our said son king Henry, nor our well beloved Philip duke of Burgundy, shall enter into any treaty of peace or concord with the said Charles, without the consent of us three and of our council, and the three estates of the realm for that purpose assembled.(29. In consideration of the frightful and astounding crimes and misdeeds committed against the kingdom of France by Charles, the said Dauphin, it is agreed that we, our son Henry, and also our very dear son Philip, duke of Burgundy, will never treat for peace or amity with the said Charles.)30. It is agreed, that in addition to the above articles being sealed with our great seal, we shall deliver to our said son king Henry, confirmatory letters from our said consort the queen, from our said well-beloved Philip duke of Burgundy, and from others of our blood royal, the great lords, barons, and cities, and towns under our obedience, and from all from whom our said son king Henry may wish to have them.

31. In like manner, our said son king Henry, on his part, shall deliver to us, besides the treaty itself sealed with his great seal, ratifications of the same from his well-beloved brothers, the great lords of his realm, and from all the principal cities and towns of his kingdom, and from any others from whom we may choose to demand them.In regard to the above articles, we, Charles king of France, do most solemnly, on the word of a king, promise and engage punctually to observe them; and we swear on the holy Evangelists, personally touched by us, to keep every article of this peace inviolate, and to make all our subjects do the same, without any fraud or deceit whatever, so that none of our heirs may in time to come infringe them, but that they may be for ever stable and firm.In confirmation whereof, we have affixed our seal to these presents.Given at Troyes, 21st day of May, in the year 1420, and of our reign the 40th.Sealed at Paris with our signet, in the absence of the great seal.Signed by the king in his grand council.Countersigned,J. Millet

Sunday, June 14, 2009

The writer who is called the Bourgeois simply because he was a resident of Paris, tells us virtually nothing about himself and in fact only speaks in the first person a few times in the Journal.2 So sadly he remains anonymous. There have been various attempts to identify him but the most that can be said is that he was likely associated with the University of Paris and probably in lower clerical orders, perhaps a Deacon. Also from his descriptions of his times and the cost of goods and food, he was probably middle class and most of the time was able to get by. It is also likely that he owned his own house.3 Aside from the above there is little that we can say about him in respect to his position and / or name. About his personality that is a different matter.

France at the time was being torn about by the scourge of internal discord, climaxing in civil war and foreign invasion by the English in the latter part of the Hundred Years War, (1337 – 1453 C.E.). This journal is a record of what it was like to live as a more or less “ordinary” citizen in what was one of the epicentres of violence and discord during the latter part of the Hundred Years War.4

In 1380 C.E. Charles VI had become King of France at a time when the tide had turned against England in the Hundred Years War and a more or less uneasy peace broken by bouts of fighting had settled between England and France. In 1377 the young Richard II had become King of England, the reign of two young kings at the same time had fed the need for peace.5

Unfortunately in 1399 C.E. Richard II was overthrown and later murdered by Henry IV, and he was from the party interested in restarting the war. But in France far worst developments happened. Charles VI started going mad intermittently. This not only created instability in the center it also created two antagonistic parties.6

The parties were the Orleanists (later Armagnacs) party and the Burgundians. The Orleanists were led at first by Louis Duke of Orleans and later by the Count of Armagnac. The Burgundians were led by the various Dukes. First Jean sans Peur (the fearless) and then Philippe le Bon (the good), of Burgundy. At first it was mere intriguing for position / power; during the periods that Charles VI was sane Louis would dominate and during the period Charles VI was insane Burgundy would dominate. It however escalated. In 1407 C.E., Jean Duke of Burgundy had Louis assassinated. Jean was able to get a royal pardon but things got worst with tit for tat massacres by each party of members of the other party including some horrible ones in Paris.7

It is important to remember that the writer of the Journal was a convinced Burgundian and that this out look colours much that he writes. Still his Journal is an invaluable source.

It is of interest that certain passages of the journal are lost forever. This includes a rather fragmentary beginning which indicates that some material was lost and certain sections in main body of the Journal. The most important section lost is the section describing the murder of Jean Duke of Burgundy in 1419. It is suspected that the author may have expressed himself a little too freely about what he thought about the Dauphin Charles’ involvement in the murder and later decided for the sake of his own life to remove the passage.9

But perhaps the flavour of the book can be understood by quoting a few passages from the book.

For example in the year 1436 C.E. our author records regarding the price of cherries:

Cherries were very plentiful this year, so much so that they were selling at a pound for one penny tournais, or even six pounds for one fourpenny blanc parisis. They lasted till mid August Lady day.10

The heat at this time, towards the end of August, was tremendous, both day and night. Neither man nor women could get to sleep at night; also many people died of plague and of epidemic, young people and children especially.11

Then the goddess of Discord arose in the castle of Ill Counsel; she woke Anger the lunatic, Greed, Madness, and Revenge; they armed themselves and contemptuously cast Reason, Justice, Remembrance of God, and Moderation out from among them.

Then insane Madness, Murder and Slaughter slew, murdered, slaughtered, and killed everyone they could find in the prisons without mercy, justly or unjustly, with cause or without.

…

…the corpses were so cut and stabbed about the face that no one could tell who they were, except the Constable and the Chancellor; they were identified by the beds they were killed in.13

Never since God was born did anyone, Saracen or any others, do such destruction in France.14

About Jeanne D’Arcs death our author says:Such and worst were my lady Jeanne’s false errors. They were all declared to her in front of the people, who were horrified when they heard these great errors against our faith which she held and still did hold. For however clearly her great crimes and errors were shown to her, she never faltered or was ashamed, but replied boldly to All the articles like one wholly given over to Satan.15

It is interesting to note that in our authors description of Charles VII’s coronation campaign, (in 1429 C.E.), although there is a description of the taking of towns and the assault on Paris in September of that year, there is no mention of Charles VII coronation at Rheims in July 1429.17 It can be speculated that the event was so shocking to his belief in the justice of his cause that he could not bear to record it.There were many people there and in other places who said that she was martyred and for her true lord. Others that she was not, and that he who had supported her so long had done wrong. Such things people said, but whatever good or whatever evil she did, she was burned that day.16

Latter, 1440 C.E., a certain imposture named Claude des Armoises claimed to be Jeanne D’Arc our author records:

When she was near Paris this great mistake of believing her to be the Maid sprang up again, so that the University and the Parlement had her brought to Paris whether she liked it or not and shown to the people at the Palais on the marble slab in the great courtyard. There a sermon was preached about her and all her life and estate set forth. She was not a maid, he said, but had been married to a knight and borne him two sons.18The change of fortune of his side along with the fact that our Author was never very enamoured or impressed with the English helped bring about a change of loyalties for the Author. Although he never talks about it explicitly the change seems to have been difficult for him.

Our Author’s description of the coronation of Henry VI of England as King of France in 1431 is as follows:

On the day after Christmas, St. Stephen’s day, the King left Paris without granting any of the benefits expected of him – release of prisoners, abolition of such evil taxes as imposts, salt taxes, fourths, and similar bad customs that are contrary to law and right. Not a soul, at home or abroad, was heard to speak a word in his praise – yet Paris had done more honour to him than to any king both when he arrived and at his consecration, considering, of course, how few people there were, how little money anyone could earn, that it was the very heart of winter, and all provisions desperately dear, especially wood.19

Another contrast is between his rather brief and laconic description of the death of Henry V of England,20 (In 1422 C.E.) and his description of the death of Charles VI of France.21

On the last day of August, a Sunday, Henry, King of England, and at the time Regent of France, died at Bois des Vincennes.

…

His [Charles VI] people and his servants were there; they mourned and lamented their loss, and so especially did the common people of Paris, calling out as he was carried through the streets, ‘Ah, dear prince, we shall never see you again, we shall never have one another so good! Accursed death! We shall never have peace now that you have left us. You go to your rest; we are left in all suffering and sorrow! The way we are going we shall soon be as wretched as the children of Israel when they were lead away into Babylon.’ Such were the things the people said, with said sighs and groans and lamentations.22

A contrast to the English view of Henry V.

In 1436 after the Burgundians changed sides Paris was retaken by the French. And much to the joy and frank disbelief of our Author the retaking of Paris was accompanied by surprisingly little mayhem or destruction or loss of life.

…but nobody, whatever his rank or his native language or whatever crimes he had committed against the King [Charles VII], nobody was killed for it.23

The English do not come off well in the Journal:

The people could not earn a farthing at any kind of work, for indeed, the English ruled Paris for a very long time, but I do honestly think that never anyone of them had any corn or oats sown or so much as a fireplace built in a house – except the Regent, the Duke of Bedford. [died September 1435] He was always building, wherever he was; his nature was quite un-English, for he never wanted to make war on anybody, whereas the English, essentially, are always wanting to make war on their neighbours without cause. That is why they all die an evil death; more than seventy-six thousand of them had by now died in France.24

Our Author complains about the heavy tax burden caused by the war:

First of all they levied a heavy tax on the clergy, then on the richer merchants, men and women. They paid four thousand francs, three thousand francs or two thousand francs, eight hundred or six hundred, each according to their estate. After that the less wealthy paid a hundred or sixty, fifty or forty; the very least paid between ten and twenty francs, none more than twenty and none less than ten. Others poorer still paid not more than hundred shillings parisis and not less than forty.25

At that time the English would sometimes take one fortress from the Armagnacs in the morning and lose two in the evening. So this war, accursed of God continued.26

After a brief description of the Taking Rouen [1449 C.E.] from the English and the celebrations in Paris of that event, the Journal ends. Whether the Author simply got tired of doing it or died is not known. Neither can we be sure if any pages have not been lost covering subsequent years. After all given the freedom with which the Author expresses himself for the time period it is perhaps remarkable that the Journal survived.

Whoever the Author was he left a remarkable and important document for future generations to read.

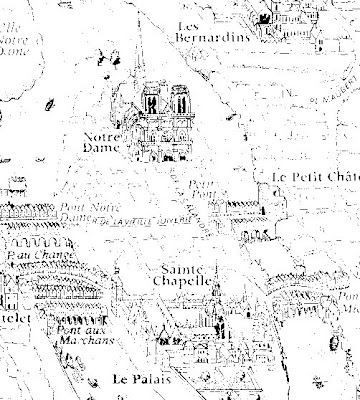

Map of Paris Mid 15th Century

Map of Paris Mid 15th Century1. Anonymous, A Parisian Journal: 1405 - 1449, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1968.

2. IBID. pp. 3-45.

3. IBID. pp. 12-24.

4. For the Hundred Years War see Starks, Michael, The Hundred Years War in France, Windrush Press, London, 2002, Burne, Alfred H., The Hundred Years War: A Military History, Penguin Books, London, 2002, Allmand, Christopher, The Hundred Years War, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1989, Seward, Desmond, The Hundred Years War, Atheneum, New York, 1978, Perroy, Edouard, The Hundred Years War, Capricorn Books, New York, 1965.

5. See Seward, pp. 127-142, Perroy, pp. 178- 206, Allmand, p. 24-26.

6. IBID. and Seward, pp. 143-152, Perroy 219-234.

7. Anonymous, pp. 116-119, Perroy p. 241.

8. Perroy, 243-265, Seward, 181-188, Stark, pp. 135-139.

9. Anonymous, pp. 41, The gap is on p. 142.

10. IBID. p. 311.

11. IBID. p. 128.

12. IBID. pp. 111-119.

13. IBID. pp 116-117.

14. IBID. p. 96.

15. IBID. p. 263.

16. IBID. p. 264. For more information on Jeanne D’Arc see Warner, Marina, Joan of Arc: The Image of Female Heroism, Penguin Books, London, 1981, Lucie-Smith, Edward, Joan of Arc, Penguin Books, London, 1976, Pernoud, Regine, & Clin, Marie – Veronique, Joan of Arc: Her Story, St. Martin Griffen, London, 1999.

17. Anonymous, pp. 238-243.

18. IBID. pp. 337. For more about Claude des Armoises see Pernoud et al, pp. 233-235, Warner, pp 191, 267-268.

19. IBID. p. 273.

20. IBID. p. 178. For a demolition of the idea of a “Romantic” Henry V and for why many Frenchmen may not be quite so impressed by him see Seward, Desmond, Henry V as Warlord, Penguin Books, London, 1987.

21. Anonymous, pp. 178-183.

22. IBID. p. 178, 180.

23. IBID. p. 306, Paris being retaken is pp. 300-307.

24. IBID. p. 307.

25. IBID. p. 317.

26. IBID. p. 191.

Pierre Cloutier

Friday, March 20, 2009

Charles VII

Charles VIIBy the terms of the treaty the English King became - Haeres et Regens Franciae – Heir to the French Throne and Regent of France – Isabeau cheerfully claiming that the Dauphin was a bastard by one of her lovers.1

The Dauphin [Charles VII] was rudely thrust aside, since this “so-called Dauphin” was, by his mother’s confession - a somewhat belated one to be sure – nothing but a bastard , born in adultery: his father’s name was not disclosed.2

Queen Isabeau

Queen IsabeauThe pertinent terms are as follows:

6. After our death, and from that time forward, the crown and kingdom of France, with all their rights and appurtenances, shall be vested permanently in our son [son-in-law], King Henry, and his heirs.

7… The power and authority to govern and to control the public affairs of the said kingdom shall, during our life-time, be vested in our son, King Henry, with the advice of the nobles and the wise men who are obedient to us, and who have consideration for the advancement and honor of the said kingdom. …

22. It is agreed that during our life-time we shall designate our son, King Henry, in the French language in this fashion, Notre tres cher fi1s Henri, Roi d' Angleterre, heritier de France,· and in the Latin language in this manner, Noster praecarissimus filius Henricus, rex Angliae, heres Francais.

24. ... It is agreed that the two kingdoms shall be governed from the time that our said son, or any of his heirs, shall assume the crown, not divided between different kings at the same time, but under one person, who shall be king and sovereign lord of both kingdoms; observing all pledges and all other things, to each kingdom its rights, liberties or customs, usages and laws, not committed in any manner one kingdom to the other.

29. In consideration of the frightful and astounding crimes and misdeeds committed against the kingdom of France by Charles, the said [also translated as “so called”] Dauphin, it is agreed that we, our son Henry, and also our very dear son Philip, duke of Burgundy, will never treat for peace or amity with the said Charles.4

Instead the Treaty claims that the Dauphin crimes and misdeeds of the Dauphin legally and legitimately entitled Charles VI to disinherit Charles VII and to make Henry V his heir. In letters issued by Charles VI, or at least in his name, in January 1420, Charles VI disinherited Charles VII for breaking the peace and for Charles VII’s involvement in the murder of the Duke of Burgundy (Jean), in 1419. Also Edward Hall a chronicler of the time has Henry V acknowledge Charles VII as “the kynges sone”, but further declares that Charles VII was deprived of his rights because “contrary to his promise & against all humaine honestie, (he) was not ashamed to polute & staine him selfe with the blood and homicide of the valeant duke of Burgoyn.”. On December 23, 1420 Charles VI and Henry V issued a joint lit de justice declaring for those reasons Charles VII disinherited.6

The story that Charles VII had doubts about his legitimacy is a charming tale but it seems to have only a very weak basis. It appears that in 1516 an author by the name of Pierre Sala in a book called Rois et Empereurs, heard from the Lord of Bisey who heard it from someone else who etc… the following tale:

The king … went one morning alone in his oratory and there made a humble silent request in the prayer to Our lord within his heart, in which he begged him devoutly that if it were true that he was his heir, descendant of the noble House of France, and that the kingdom should in justice belong to him, might it please God to protect and defend him, or at the very worst, allow him the grace of escaping alive and free from imprisonment so that he might find solace in Spain or in Scotland, which were from times long past brothers-in-arms and allies of the kings of France.7

Another question is; was Isabeau, Charles VII’s mother, a promiscuous woman? Here is where “fact” clashes with fact. The evidence for her alleged affairs turns out to be, too put it mildly, very dubious. Like the stories of her being ugly and fat, a bad wife and bad mother; it appears that the basis for such stories is less than paper thin.9

It is true that various songs and documents accused Isabeau and / or the people around her of corruption etc., but the same sources do not accuse Isabeau of adultery. In fact some of them praise Isabeau for her Christian behavior. None accuse her of adultery until there was political motive for doing so and long after the death of Louis, Duke of Orleans. (which occurred, by assassination in 1407 C.E.)10

Two sort of contemporary documents mention the alleged adultery. The first is a allegory called the Pastorelet, written after the assassination of Jean Duke of Burgundy in 1419 C.E., which depicts important people at the time has shepherds and shepherdesses, in it Charles VI learns of Louis and Isabeau’s affair and swears revenge and Jean Duke of Burgundy says he will take care of the matter. Louis’ murder by Jean is thus excused. The problem with the story is that at the time (1407 C.E.) Jean never even hinted at this affair and instead accused Louis of tyranny to justify the assassination. The political purpose of this piece of satire is so obvious, to promote the Burgundian cause, in the context of the Treaty of Troyes, it can be discounted. The chronicle Jean Chartier, writing after 1437 C.E., records in describing the death of Isabeau, that the English shortened the life of Isabeau by spreading this slander because it upset her very much.11 The reliability of this source is of course also questionable, although its of interest that a source that describes the accusation of adultery has a slander is used as evidence of its truth!

It is interesting that even after the Treaty of Troyes Isabeau tried to keep in touch with Charles VII and apparently was trying to mediate a solution despite being involved in the disinheriting of her own son.12

All of this would seem to indicate that the story of the alleged illegitimacy of Charles VII is a later legend, so too are the stories of him doubting his legitimacy and even the “fact” of the promiscuity of Isabeau, at least at the time of Charles VII’s birth is similarly a myth.

Isabeau never publicly, or privately, it seems, declared Charles VII a bastard. The public reason given for Charles VII’s disinheritance was his involvement in intrigues and the murder of Jean Duke of Burgundy. If Charles never doubted his legitimacy, which seems to be the case, then what “secret” did Joan of Arc tell Charles VII at Chinon to convince him of her mission? The answer is we do not know.13

2. Perroy, Edouard, The Hundred Years War, Capricorn Books, New York, 1965, p. 243.

3. For example Given-Wilson, Chris, & Curteis, Alice, The Royal Bastards of Medieval England, Routledge, 1984, p. 46, Marius, Richard, Thomas More, Fount Paperbacks, London, 1986, p. 109, refers to:

Queen Isabeau of France, wife to the mad King Charles VI a century before More wrote his History, claiming that her son Charles VII was not fathered by her lawful husband,…

4. Ogg, Frederic Austin, A Source Book of Medieval History, American Books Company, New York, 1907, p. 443.

5. Gibbons, Rachel, Isabeau of Bavaria, Queen of France (1385-1422): The Creation of an Historical Villainess, Transactions of the Royal Society, Sixth Series, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1996, pp. 51- 73, at. pp. 69-70, Seward, Desmond, Henry V as Warlord, Penguin Books, London, 1987, pp. 143-145.

6. IBID. Gibbons, pp. 70-71.

7. Pernoud, Regine, & Clin, Marie-Veronique, Joan of Arc, St. Martin’s Griffin, New York,1998, p. 24.

8. IBID. pp. 23-25, Warner, Marina, Joan of Arc, Penguin Books, 1981, pp. 72-75.

9. See Gibbons, Rachel for many examples.

10. IBID. pp. 64-67.

11. IBID. 67-68.

12. IBID. p. 68.

13, Warner, pp. 70-77.