|

| Jeanne d'Arc |

Wednesday, February 13, 2013

Tuesday, February 28, 2012

|

| Book Cover |

Monday, February 07, 2011

English Forces Sent to Northern France 1415-1453

Year

1415 10,435

1416 0?

1417 10,809

1418 2,000

1419 0?

Total 23,244

AVP14,649

1420 1,275

1421 4,100

1422 1,079

1423 1,520

1424 2,209

1425 1,396

1426 800

1427 1,200

1428 2,694

1429 1,800

Total 18,073

AVP 1,807

1430 7,991

1431 3,448

1432 1,220

1433 1,110

1434 2,088

1435 1,987

1436 7,926

1437 2,067

1438 1,646

1439 963

Total 30,446

AVP 3,045

1440 2,081

1441 3,798

1442 2,500

1443 4,549

14442400

Total 13,328

AVP 2,666

1448 1,000

1449 963

145033,035

Total 4,998

AVP 1,666

G.T.471,494

1415-1419, Total – 23,724 AVP – 4,745

1420-1429, Total - 18,473 AVP – 1,847

1430-1439, Total - 41,039 AVP – 4,104

1440-1444, Total - 14,448 AVP – 2,890

1448-1450, Total - 4,998 AVP – 1,666

1451-1453, Total - 7,324 AVP - 2,442

Grand Total - 91,4125

Sunday, June 14, 2009

The writer who is called the Bourgeois simply because he was a resident of Paris, tells us virtually nothing about himself and in fact only speaks in the first person a few times in the Journal.2 So sadly he remains anonymous. There have been various attempts to identify him but the most that can be said is that he was likely associated with the University of Paris and probably in lower clerical orders, perhaps a Deacon. Also from his descriptions of his times and the cost of goods and food, he was probably middle class and most of the time was able to get by. It is also likely that he owned his own house.3 Aside from the above there is little that we can say about him in respect to his position and / or name. About his personality that is a different matter.

France at the time was being torn about by the scourge of internal discord, climaxing in civil war and foreign invasion by the English in the latter part of the Hundred Years War, (1337 – 1453 C.E.). This journal is a record of what it was like to live as a more or less “ordinary” citizen in what was one of the epicentres of violence and discord during the latter part of the Hundred Years War.4

In 1380 C.E. Charles VI had become King of France at a time when the tide had turned against England in the Hundred Years War and a more or less uneasy peace broken by bouts of fighting had settled between England and France. In 1377 the young Richard II had become King of England, the reign of two young kings at the same time had fed the need for peace.5

Unfortunately in 1399 C.E. Richard II was overthrown and later murdered by Henry IV, and he was from the party interested in restarting the war. But in France far worst developments happened. Charles VI started going mad intermittently. This not only created instability in the center it also created two antagonistic parties.6

The parties were the Orleanists (later Armagnacs) party and the Burgundians. The Orleanists were led at first by Louis Duke of Orleans and later by the Count of Armagnac. The Burgundians were led by the various Dukes. First Jean sans Peur (the fearless) and then Philippe le Bon (the good), of Burgundy. At first it was mere intriguing for position / power; during the periods that Charles VI was sane Louis would dominate and during the period Charles VI was insane Burgundy would dominate. It however escalated. In 1407 C.E., Jean Duke of Burgundy had Louis assassinated. Jean was able to get a royal pardon but things got worst with tit for tat massacres by each party of members of the other party including some horrible ones in Paris.7

It is important to remember that the writer of the Journal was a convinced Burgundian and that this out look colours much that he writes. Still his Journal is an invaluable source.

It is of interest that certain passages of the journal are lost forever. This includes a rather fragmentary beginning which indicates that some material was lost and certain sections in main body of the Journal. The most important section lost is the section describing the murder of Jean Duke of Burgundy in 1419. It is suspected that the author may have expressed himself a little too freely about what he thought about the Dauphin Charles’ involvement in the murder and later decided for the sake of his own life to remove the passage.9

But perhaps the flavour of the book can be understood by quoting a few passages from the book.

For example in the year 1436 C.E. our author records regarding the price of cherries:

Cherries were very plentiful this year, so much so that they were selling at a pound for one penny tournais, or even six pounds for one fourpenny blanc parisis. They lasted till mid August Lady day.10

The heat at this time, towards the end of August, was tremendous, both day and night. Neither man nor women could get to sleep at night; also many people died of plague and of epidemic, young people and children especially.11

Then the goddess of Discord arose in the castle of Ill Counsel; she woke Anger the lunatic, Greed, Madness, and Revenge; they armed themselves and contemptuously cast Reason, Justice, Remembrance of God, and Moderation out from among them.

Then insane Madness, Murder and Slaughter slew, murdered, slaughtered, and killed everyone they could find in the prisons without mercy, justly or unjustly, with cause or without.

…

…the corpses were so cut and stabbed about the face that no one could tell who they were, except the Constable and the Chancellor; they were identified by the beds they were killed in.13

Never since God was born did anyone, Saracen or any others, do such destruction in France.14

About Jeanne D’Arcs death our author says:Such and worst were my lady Jeanne’s false errors. They were all declared to her in front of the people, who were horrified when they heard these great errors against our faith which she held and still did hold. For however clearly her great crimes and errors were shown to her, she never faltered or was ashamed, but replied boldly to All the articles like one wholly given over to Satan.15

It is interesting to note that in our authors description of Charles VII’s coronation campaign, (in 1429 C.E.), although there is a description of the taking of towns and the assault on Paris in September of that year, there is no mention of Charles VII coronation at Rheims in July 1429.17 It can be speculated that the event was so shocking to his belief in the justice of his cause that he could not bear to record it.There were many people there and in other places who said that she was martyred and for her true lord. Others that she was not, and that he who had supported her so long had done wrong. Such things people said, but whatever good or whatever evil she did, she was burned that day.16

Latter, 1440 C.E., a certain imposture named Claude des Armoises claimed to be Jeanne D’Arc our author records:

When she was near Paris this great mistake of believing her to be the Maid sprang up again, so that the University and the Parlement had her brought to Paris whether she liked it or not and shown to the people at the Palais on the marble slab in the great courtyard. There a sermon was preached about her and all her life and estate set forth. She was not a maid, he said, but had been married to a knight and borne him two sons.18The change of fortune of his side along with the fact that our Author was never very enamoured or impressed with the English helped bring about a change of loyalties for the Author. Although he never talks about it explicitly the change seems to have been difficult for him.

Our Author’s description of the coronation of Henry VI of England as King of France in 1431 is as follows:

On the day after Christmas, St. Stephen’s day, the King left Paris without granting any of the benefits expected of him – release of prisoners, abolition of such evil taxes as imposts, salt taxes, fourths, and similar bad customs that are contrary to law and right. Not a soul, at home or abroad, was heard to speak a word in his praise – yet Paris had done more honour to him than to any king both when he arrived and at his consecration, considering, of course, how few people there were, how little money anyone could earn, that it was the very heart of winter, and all provisions desperately dear, especially wood.19

Another contrast is between his rather brief and laconic description of the death of Henry V of England,20 (In 1422 C.E.) and his description of the death of Charles VI of France.21

On the last day of August, a Sunday, Henry, King of England, and at the time Regent of France, died at Bois des Vincennes.

…

His [Charles VI] people and his servants were there; they mourned and lamented their loss, and so especially did the common people of Paris, calling out as he was carried through the streets, ‘Ah, dear prince, we shall never see you again, we shall never have one another so good! Accursed death! We shall never have peace now that you have left us. You go to your rest; we are left in all suffering and sorrow! The way we are going we shall soon be as wretched as the children of Israel when they were lead away into Babylon.’ Such were the things the people said, with said sighs and groans and lamentations.22

A contrast to the English view of Henry V.

In 1436 after the Burgundians changed sides Paris was retaken by the French. And much to the joy and frank disbelief of our Author the retaking of Paris was accompanied by surprisingly little mayhem or destruction or loss of life.

…but nobody, whatever his rank or his native language or whatever crimes he had committed against the King [Charles VII], nobody was killed for it.23

The English do not come off well in the Journal:

The people could not earn a farthing at any kind of work, for indeed, the English ruled Paris for a very long time, but I do honestly think that never anyone of them had any corn or oats sown or so much as a fireplace built in a house – except the Regent, the Duke of Bedford. [died September 1435] He was always building, wherever he was; his nature was quite un-English, for he never wanted to make war on anybody, whereas the English, essentially, are always wanting to make war on their neighbours without cause. That is why they all die an evil death; more than seventy-six thousand of them had by now died in France.24

Our Author complains about the heavy tax burden caused by the war:

First of all they levied a heavy tax on the clergy, then on the richer merchants, men and women. They paid four thousand francs, three thousand francs or two thousand francs, eight hundred or six hundred, each according to their estate. After that the less wealthy paid a hundred or sixty, fifty or forty; the very least paid between ten and twenty francs, none more than twenty and none less than ten. Others poorer still paid not more than hundred shillings parisis and not less than forty.25

At that time the English would sometimes take one fortress from the Armagnacs in the morning and lose two in the evening. So this war, accursed of God continued.26

After a brief description of the Taking Rouen [1449 C.E.] from the English and the celebrations in Paris of that event, the Journal ends. Whether the Author simply got tired of doing it or died is not known. Neither can we be sure if any pages have not been lost covering subsequent years. After all given the freedom with which the Author expresses himself for the time period it is perhaps remarkable that the Journal survived.

Whoever the Author was he left a remarkable and important document for future generations to read.

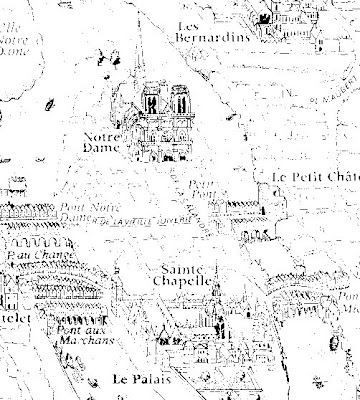

Map of Paris Mid 15th Century

Map of Paris Mid 15th Century1. Anonymous, A Parisian Journal: 1405 - 1449, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1968.

2. IBID. pp. 3-45.

3. IBID. pp. 12-24.

4. For the Hundred Years War see Starks, Michael, The Hundred Years War in France, Windrush Press, London, 2002, Burne, Alfred H., The Hundred Years War: A Military History, Penguin Books, London, 2002, Allmand, Christopher, The Hundred Years War, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1989, Seward, Desmond, The Hundred Years War, Atheneum, New York, 1978, Perroy, Edouard, The Hundred Years War, Capricorn Books, New York, 1965.

5. See Seward, pp. 127-142, Perroy, pp. 178- 206, Allmand, p. 24-26.

6. IBID. and Seward, pp. 143-152, Perroy 219-234.

7. Anonymous, pp. 116-119, Perroy p. 241.

8. Perroy, 243-265, Seward, 181-188, Stark, pp. 135-139.

9. Anonymous, pp. 41, The gap is on p. 142.

10. IBID. p. 311.

11. IBID. p. 128.

12. IBID. pp. 111-119.

13. IBID. pp 116-117.

14. IBID. p. 96.

15. IBID. p. 263.

16. IBID. p. 264. For more information on Jeanne D’Arc see Warner, Marina, Joan of Arc: The Image of Female Heroism, Penguin Books, London, 1981, Lucie-Smith, Edward, Joan of Arc, Penguin Books, London, 1976, Pernoud, Regine, & Clin, Marie – Veronique, Joan of Arc: Her Story, St. Martin Griffen, London, 1999.

17. Anonymous, pp. 238-243.

18. IBID. pp. 337. For more about Claude des Armoises see Pernoud et al, pp. 233-235, Warner, pp 191, 267-268.

19. IBID. p. 273.

20. IBID. p. 178. For a demolition of the idea of a “Romantic” Henry V and for why many Frenchmen may not be quite so impressed by him see Seward, Desmond, Henry V as Warlord, Penguin Books, London, 1987.

21. Anonymous, pp. 178-183.

22. IBID. p. 178, 180.

23. IBID. p. 306, Paris being retaken is pp. 300-307.

24. IBID. p. 307.

25. IBID. p. 317.

26. IBID. p. 191.

Pierre Cloutier

Friday, March 20, 2009

Charles VII

Charles VIIBy the terms of the treaty the English King became - Haeres et Regens Franciae – Heir to the French Throne and Regent of France – Isabeau cheerfully claiming that the Dauphin was a bastard by one of her lovers.1

The Dauphin [Charles VII] was rudely thrust aside, since this “so-called Dauphin” was, by his mother’s confession - a somewhat belated one to be sure – nothing but a bastard , born in adultery: his father’s name was not disclosed.2

Queen Isabeau

Queen IsabeauThe pertinent terms are as follows:

6. After our death, and from that time forward, the crown and kingdom of France, with all their rights and appurtenances, shall be vested permanently in our son [son-in-law], King Henry, and his heirs.

7… The power and authority to govern and to control the public affairs of the said kingdom shall, during our life-time, be vested in our son, King Henry, with the advice of the nobles and the wise men who are obedient to us, and who have consideration for the advancement and honor of the said kingdom. …

22. It is agreed that during our life-time we shall designate our son, King Henry, in the French language in this fashion, Notre tres cher fi1s Henri, Roi d' Angleterre, heritier de France,· and in the Latin language in this manner, Noster praecarissimus filius Henricus, rex Angliae, heres Francais.

24. ... It is agreed that the two kingdoms shall be governed from the time that our said son, or any of his heirs, shall assume the crown, not divided between different kings at the same time, but under one person, who shall be king and sovereign lord of both kingdoms; observing all pledges and all other things, to each kingdom its rights, liberties or customs, usages and laws, not committed in any manner one kingdom to the other.

29. In consideration of the frightful and astounding crimes and misdeeds committed against the kingdom of France by Charles, the said [also translated as “so called”] Dauphin, it is agreed that we, our son Henry, and also our very dear son Philip, duke of Burgundy, will never treat for peace or amity with the said Charles.4

Instead the Treaty claims that the Dauphin crimes and misdeeds of the Dauphin legally and legitimately entitled Charles VI to disinherit Charles VII and to make Henry V his heir. In letters issued by Charles VI, or at least in his name, in January 1420, Charles VI disinherited Charles VII for breaking the peace and for Charles VII’s involvement in the murder of the Duke of Burgundy (Jean), in 1419. Also Edward Hall a chronicler of the time has Henry V acknowledge Charles VII as “the kynges sone”, but further declares that Charles VII was deprived of his rights because “contrary to his promise & against all humaine honestie, (he) was not ashamed to polute & staine him selfe with the blood and homicide of the valeant duke of Burgoyn.”. On December 23, 1420 Charles VI and Henry V issued a joint lit de justice declaring for those reasons Charles VII disinherited.6

The story that Charles VII had doubts about his legitimacy is a charming tale but it seems to have only a very weak basis. It appears that in 1516 an author by the name of Pierre Sala in a book called Rois et Empereurs, heard from the Lord of Bisey who heard it from someone else who etc… the following tale:

The king … went one morning alone in his oratory and there made a humble silent request in the prayer to Our lord within his heart, in which he begged him devoutly that if it were true that he was his heir, descendant of the noble House of France, and that the kingdom should in justice belong to him, might it please God to protect and defend him, or at the very worst, allow him the grace of escaping alive and free from imprisonment so that he might find solace in Spain or in Scotland, which were from times long past brothers-in-arms and allies of the kings of France.7

Another question is; was Isabeau, Charles VII’s mother, a promiscuous woman? Here is where “fact” clashes with fact. The evidence for her alleged affairs turns out to be, too put it mildly, very dubious. Like the stories of her being ugly and fat, a bad wife and bad mother; it appears that the basis for such stories is less than paper thin.9

It is true that various songs and documents accused Isabeau and / or the people around her of corruption etc., but the same sources do not accuse Isabeau of adultery. In fact some of them praise Isabeau for her Christian behavior. None accuse her of adultery until there was political motive for doing so and long after the death of Louis, Duke of Orleans. (which occurred, by assassination in 1407 C.E.)10

Two sort of contemporary documents mention the alleged adultery. The first is a allegory called the Pastorelet, written after the assassination of Jean Duke of Burgundy in 1419 C.E., which depicts important people at the time has shepherds and shepherdesses, in it Charles VI learns of Louis and Isabeau’s affair and swears revenge and Jean Duke of Burgundy says he will take care of the matter. Louis’ murder by Jean is thus excused. The problem with the story is that at the time (1407 C.E.) Jean never even hinted at this affair and instead accused Louis of tyranny to justify the assassination. The political purpose of this piece of satire is so obvious, to promote the Burgundian cause, in the context of the Treaty of Troyes, it can be discounted. The chronicle Jean Chartier, writing after 1437 C.E., records in describing the death of Isabeau, that the English shortened the life of Isabeau by spreading this slander because it upset her very much.11 The reliability of this source is of course also questionable, although its of interest that a source that describes the accusation of adultery has a slander is used as evidence of its truth!

It is interesting that even after the Treaty of Troyes Isabeau tried to keep in touch with Charles VII and apparently was trying to mediate a solution despite being involved in the disinheriting of her own son.12

All of this would seem to indicate that the story of the alleged illegitimacy of Charles VII is a later legend, so too are the stories of him doubting his legitimacy and even the “fact” of the promiscuity of Isabeau, at least at the time of Charles VII’s birth is similarly a myth.

Isabeau never publicly, or privately, it seems, declared Charles VII a bastard. The public reason given for Charles VII’s disinheritance was his involvement in intrigues and the murder of Jean Duke of Burgundy. If Charles never doubted his legitimacy, which seems to be the case, then what “secret” did Joan of Arc tell Charles VII at Chinon to convince him of her mission? The answer is we do not know.13

2. Perroy, Edouard, The Hundred Years War, Capricorn Books, New York, 1965, p. 243.

3. For example Given-Wilson, Chris, & Curteis, Alice, The Royal Bastards of Medieval England, Routledge, 1984, p. 46, Marius, Richard, Thomas More, Fount Paperbacks, London, 1986, p. 109, refers to:

Queen Isabeau of France, wife to the mad King Charles VI a century before More wrote his History, claiming that her son Charles VII was not fathered by her lawful husband,…

4. Ogg, Frederic Austin, A Source Book of Medieval History, American Books Company, New York, 1907, p. 443.

5. Gibbons, Rachel, Isabeau of Bavaria, Queen of France (1385-1422): The Creation of an Historical Villainess, Transactions of the Royal Society, Sixth Series, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1996, pp. 51- 73, at. pp. 69-70, Seward, Desmond, Henry V as Warlord, Penguin Books, London, 1987, pp. 143-145.

6. IBID. Gibbons, pp. 70-71.

7. Pernoud, Regine, & Clin, Marie-Veronique, Joan of Arc, St. Martin’s Griffin, New York,1998, p. 24.

8. IBID. pp. 23-25, Warner, Marina, Joan of Arc, Penguin Books, 1981, pp. 72-75.

9. See Gibbons, Rachel for many examples.

10. IBID. pp. 64-67.

11. IBID. 67-68.

12. IBID. p. 68.

13, Warner, pp. 70-77.