|

| Empress Wu Zetian |

Sunday, July 07, 2013

Wednesday, June 05, 2013

|

| Taiping Imperial Seal |

Saturday, March 09, 2013

Sunday, March 03, 2013

Tuesday, November 08, 2011

|

| Great Bath at Mohenjodaro Indus Civilization c. 2300 B.C.E. |

Thursday, August 26, 2010

The below is my list in order of importance of the top ten events of the last 2000 years (1 - 2000 C.E.).

1, The life, teachings and death of Jesus. (B.C.E. 5 - 30 C.E. ?) Considering the impact of his life and death on the world this is an obvious choice for number one.

3, The discovery and diffusion of Printing, from China to the rest of the world. (c. 800 C.E.) The incredible impact of printing on culture and intellectual activity, first in China and then in Europe and then the rest of the world are manifold.

5, Wen founder of the Sui dynasty, reunifies China after 270 years of division. (C.E. 589) Its hard to imagine what the world would have been like with a permanently disunited China, and this further establishes the period of Chinese economic primacy that lasts for over 1000 years.

8, Gunpowder invented and refined in China. (c. 800 - 1000 C.E.) Invention spread to the rest of the world with vast consequences, later Gunpowder weapons developed in China and spread to rest of world, for further refinement. First metal cannon c. 1270 in China.

9, The Invention and spread of "Arabic" numerals from India. (c. 350 C.E.)

Sunday, February 14, 2010

Allied with this concept is the notion in western historiography of the Asiatic horde. In this concept the "West" as been frequently threatened by "Asiatic hordes" that threaten to overwhelm Europe with hugely superior numbers and subject the west to Asiatic despotism. Thus battles from Marathon, 490 B.C.E., to Vienna, 1683 C.E., are characterized as fights against Europe i.e., the “West”, being overwhelmed by the hordes of Asia.2 “Asia” is the big bogyman other that threatens the innocent progressive “West”. Of course what exactly is “Asia” is poorly defined if at all. It is simply a cliche of little real content but much propagandistic hyperbole. Allied to this the concept of the Asiatic horde necessarily requires that the “Asiatic” armies be huge and the plucky European armies, fighting for truth, virtue and the European way be much smaller, but of course by pluck, luck and skill they defeat the huge Asiatic horde and save Europe from a fate worst than death, i.e., Asiatic sloth, corruption and decadence. Of course it is a collection of cliches that go back to the Greeks and they are of course of little validity.2

European armies are not only characterized as much smaller than the Asiatic horde but they are almost always characterized as more efficient and professional, which is what supposedly enables them to defeat the huge Asiatic hordes. Asia is always that which from outside Europe is threatening to overwhelm poor small Europe.3 Allied to this is the poisonous and utterly false notion that that the “West” is the unique heir of Greco-Roman civilization and that civilizations like the Islamic are “Asiatic” and outside that tradition. This is nonsense. Islam is the heir to Greece and Rome just as much as the “West” is. Further it is curious that although “Western” civilization is frequently described as Judeo-Christian; Middle Eastern civilization is never described as Judeo-Christian-Islamic. The need to cast Islamic civilization as the “Asiatic” other is rather obvious.

Now the above mentioned cliches can be criticized at every level. For example, lumping all the cultures of Asia under the term “Asiatic” is stunningly simpleminded. Further isn’t Europe a part of Asia and so “Asiatic”? As mentioned above the separation of Islam as wholly separated from the “west” and “Asiatic” is also dubious. Such things as the concept of the huge “Asiatic” army, relying solely on numbers against the smaller professional European army are cliches not realities of the past.4

Other conceits like the idea that everything that happens is for the best and history represents an upward process of progress are also in this view of the past. But one thing is omnipresent the small free professional European army that beats the huge unprofessional despotic, decadent army of “Asiatics” through sheer skill and fighting ability and thus preserves “Western” civilization from being destroyed or turned into just another stronghold of “Asiatic” despotism.5

However in this story of the triumph of the “West” towards it “inevitable” rise to global supremacy which by virtue of its considerable merits it undoubtedly deserved that happened an event that must with great effort be excised and made harmless and wholesome. It cannot be ignored but it must be purged as a decisive event because of what it reveals about the real state of the “West” at the time and the actual realities of the world then. Of course I am being facetious about the “West’s” domination being deserved out of the “West’s” intrinsic merits that is just a conceit worthy of ridicule although taken seriously as recently as a century ago.6 The event that should actually be a centrepiece in the history of the world but has been purged out as a central event because it reveals both the military and cultural weakness of the “West” at the time is the Mongol invasion of Europe 1237-1241 C.E.

Here was no decisive battle that saved the “West” no grand demonstration of “Western” military superiority instead what was revealed was the political, military and yes cultural weakness of the “West” when faced with the armies of the Mongols. The patent and pathetic inability of the armies of the “West” to hold off the Mongols is a graphic demonstration of the marginality and weakness of the “West” in comparison to the rest of the world at that time. It has become customary among some to talk about a “Western” way of war and by implication at least, to talk about the superiority of this method of war fighting. The argument being that “Western” ways of war fighting are superior. This is bluntly dubious. The Mongols are a glaring example about how false that is. Of course the usual reaction is talk about the Mongols being “exceptions”. This is poppycock. Instead one should be examining weather or not the very idea of a superior “Western” way of war is in fact true. But then a superior “Western” way of war goes with the concept of small, professional European armies defeating huge “Asiatic” hordes of warriors ruled by decadent, despotic elites. In other words it is flattering to European notions of superiority.7

As I said the Mongol invasions are quite brutal indications of the reality of war making in that period. The simple fact is that the Mongol armies were crushingly and massively superior to the armies of the Europeans and they demonstrated it repeatedly during the campaign. The following is a brief run through of the Mongol campaign in Europe.

In the years 1221-1224 C.E. Genghis Khan sent an army under one of his general’s, Subotai, to check out the lands further west. After going through northern Iran and travelling through the Caucasus, were they crushed the Georgians, they emerged in the plains of southern Russian where they engaged the nomadic Cumans in a war during which the Mongols were victorious. Afterwards they invaded the Crimea where they stormed several Genoese trading settlements. During the winter of 1222-1223 while they wintered besides the Black sea spies were sent to scout out the situation in Europe. In the year 1223 as the Mongols were preparing to return to Mongolia. A combined Russian-Cuman army advanced on them. In a fit of extraordinary stupidity the envoys that Subotai sent to make a deal with the Russian – Cuman army were murdered. By then the Mongols simply wanted to retire from the area with no conflict. The result was disaster.

At the battle of the Kalka river, superior Mongol strategy and tactics resulted in an overwhelming Mongol victory. The murder of the Mongol envoys ensured that the battle was followed by a wholesale massacre. The commanders of the army that the Mongols captured were brutally pressed to death. Most figures for the battle give the Mongols c. 25,000 men and their enemies up to 75,000. This is false. It is unlikely that the Mongols were up to full strength; by then they probably numbered less than 15,000 and it unlikely that the Russian-Cuman army numbered much more than 30,000 men. Afterwards the Mongols after an indecisive battle with the Volga Bulgars withdrew to Mongolia.8

The knowledge that the Mongols gained in this incursion would help them in their next invasion. But in the meantime the Mongols were engaged in a war with the Chin empire that controlled northern China and so were delayed in returning to the west.

It wasn’t until 1235 C.E. that the new Mongol Khan Ogatai who had succeeded his father Genghis in 1227 decided to follow up the reconnaissance of 1221-1224 C.E.

The army was under the nominal command of Batu a grandson of Genghis Khan, the actual commander was Subotai who had lead the reconnaissance of 1221-1224 C.E.

In December of 1237 C.E. The Mongols invaded across the Volga river. Some accounts give their numbers as 150,000 men. This is false the actual total seems to be c. 50,000. The Volga Bulgars were swiftly obliterated and their chief towns stormed. In the winter of 1237-1238. Previous to this the Mongols had conquered the region between the Kama and the Volga right down to the Caspian and Black sea. In a matter of a few months the Mongols stormed through central Russia wiping out several armies and storming city after city. Only a sudden thaw in February 1238 prevented the Mongols from taking Novgorod. It was a campaign of astounding swiftness during which the Mongols marched well over a thousand miles and stormed dozens of different strongholds and fortresses. Most of Russia not out right conquered submitted to the Mongols.9

For the next 2 years Subotai consolidated his conquests and planned his next move along with sending large numbers of spies to gather intelligence about Europe. During all this intelligence gathering Subotai discovered that the Europeans were fatally, almost suicidally divided and at each other’s throats. After several years of preparation Subotai moved in December 1240 C.E.

Subotai had at most 50,000 men and probably less than 40,000 it seemed an incredibly small number with which to contemplate the conquest of Europe but it was enough as the following events were to show.

Kiev was stormed and destroyed along with other fortresses and cities in southern Russia. Than Subotai advanced to the passes of the Carpathian mountains. There he divided his army into several parts.

One section went north to deal with the Poles, Lithuanians and Germans. The southern section went around the Carpathians to invade Hungary from the south. The main section crossed the passes of the Carpathians and advanced on Budapest.

The northern section, lead by the Mongol general Kaidu, probably numbering no more than 15,000 men at most and likely c. 10,000 divided into several section one swept through Lithuania where it tore apart several Lithuanian armies and stormed fortress after fortress. It then devastated Prussia, then controlled by the Teutonic Knights and smashed yet again several armies it then cut through Pomerania, It then joined the forces invading Poland invaded Poland. The united section smashed the army of Boleslav V of Poland at Krakow and then stormed the city. The section invaded Silesia where Prince Henry of Silesia tried to stop them at Liegnitz with an army composed of Poles, Germans, Teutonic knights and some Czechs, probably numbering c. 15,000-20,000 men. The Mongols at most numbered 10,000 men. The Battle of Liegnitz, (April 9, 1241), was a disaster, Prince Henry was killed and his army annihilated. The Mongols then proceed to methodically devastate Silesia and storm one town after the other. King Wenceslas of Bohemia withdrew his army into Saxony. The Mongols followed up and devastated large sections of Saxony. The Mongol army instead of continuing west suddenly turned south to unite with the central army under Subotai. They past through Moravia, which devastated by fire and sword and many of its towns stormed and ravaged.

Meanwhile Subotai was engaged with the Hungarians led by Bela IV. Probably the ablest of the opponents of the Mongols during the invasion Bela IV was completely out classed the Mongols. While Subotai devastated the area around the Budapest other sections of the Mongol army devastated Transylvania and southern Hungary. Storming town after town.

Reuniting most of his army Subotai withdrew to the Sajo river c. 100 miles from Budapest. Bela IV showing both caution and initiative followed. The army he brought with him probably numbered c. 20,000-30,000. Subotai whose army probably by then numbered 20,000 decided to comprehensively annihilate the Hungarian army. Bela IV, showing a surprising amount of energy, had seized a bridgehead over the river and fortified it. Subotai launched a holding attack on the bridgehead and quickly overwhelmed it. Then as the Hungarians came out of their fortified camp to repel the attack they were attacked in flank by the main Mongol force. By deliberately leaving a hole in their encircling forces the Mongols cause the Hungarian army to disintegrate into a mob of fugitives who were then relentlessly pursued. The Battle ended in a horrible massacre of the fugitives. So ended the Battle of the Sajo River, (April 11, 1241).

In the relentless pursuit that followed, Budapest was stormed and so was any Hungarian fortress that resisted. Bela IV fled to Dalmatia where he was relentlessly purued. Bela IV eventually was able find safety in Germany. The Austrian Duke instead of helping Bela IV imprisoned him to get some cash out of him before letting him go. An outstanding example of the suicidal divisions among the Europeans.

At the same time in several battles Transylvania was subdued and most of its town’s conquered.10 The astounding speed of this invasion and the fact that in a matter of months all eastern Europe was ravaged and conquered is one of the most stunning military campaigns in history.

Subotai spent most of the late spring, summer and fall consolidating his conquests and preparing for the next stage in the conquest of Europe. The Europeans during this brief interval were utterly unable to coordinate any of their defensive efforts as Subotai worked out his plans for invading Austria, Germany and Italy in the coming winter.

In late 1241, shortly after Christmas Mongol armies crossed the alps into northern Italy, while other forces devastated the area around Vienna. It is hard to believe that the campaign of 1241-1242 would not see the conquest of Germany and Italy at least. To be followed by France, Spain and England and then some moping up. All probably to take less than 5 more years. Possibly considerably less if the Europeans sensibly stopped fighting and submitted.

It was not to be. Instead of Europe saved by some last minute military feat, Europe was saved by the fact that the Mongol Khan Ogatai drank too much. In a night of drunken excess in the fall of 1241 Ogatai drank too much and died. THe news took a couple of months to reach the armies in Europe. But when it did the law of Genghis Khan stated.11

..after the death of the ruler all offspring of the House of Genghis Khan, wherever they might be, must return to Mongolia to take part in the election of the new Khakhan.12

There was considerable arguing among the commanders of the Mongol army. The details are fascinating in that the three Mongol Princes wanted to stay and continue the war or at least leave their armies there under subordinates to continue the war. Subotai, the military genius responsible for this spectacularly successful campaign argued for a withdrawal from central and eastern Europe, leaving some forces in southern Russia and too renew the campaign at a later date. The rest would return to Mongolia for the selection of a new Khan.

As the Mongols withdrew they went through Serbia and Bulgaria in 1242 C.E., where they, once again, cut up various armies, devastated large areas and stormed many towns and fortresses leaving behind a wasteland.13

The Europeans promptly started their suicidal infighting again, basically unmindful that the Mongols might come back. Fortunately the Mongols never did come back.

Basically the Mongols were preoccupied by internal disputes and they decided to concentrate on the conquest of all of China, a vastly more profitable and difficult challenge than Europe. This took many decades. (Until 1279 C.E.). By then the Mongol realm was divided and the Khanate of the Golden Horde that controlled the Steppes of Russia was not strong enough on its own to conquer Europe and also frankly not interested.14

The true state of actual power relations at the time is revealed by the fact that not only did it take the Mongols decades to conquer all of China, (almost 70 years), but the armies they used were vastly larger in the order of 150,000 – 200,000 men by 1270 C.E. Further there was no equivalent in the conquest of China of a spectacular conquest like that of Eastern Europe in 1240-1241 C.E. There a Mongol army of c. 50,000 sufficed to crush eastern Europe in a few months whereas Mongol armies of a similar size had trouble conquering a single Chinese province. Compared to China Europe at the time was weak and no match for the Mongols. It is fortunate for Europe that the Mongols after this invasion were so fixated on China that it consumed their main efforts for decades. By the time China was conquered the Mongols were both unable and unwilling to renew the conquest of Europe. So in a way China saved Europe from the Mongols.

Traditionally the nomadic armies of the steppes could be quite formidable their chief weakness was lack of logistic support and the inability to storm cites and strongholds.

Genghis Khan solved those problems in combination of ways. The Mongol armies were highly mobile; each fighting man had at least 4-5 and usually more spare mounts. Discipline was ferocious and training comprehensive. The Mongol armies were able to move at truly spectacular speeds due to their vast array of horses and other support animals to cart supplies etc. The logistic problems of gathering supplies were solved by an efficient commissariat that used the bureaucratic techniques of the Chinese with Chinese technical experts to organize such things. Giving the Mongols an effective logistical setup. Further Chinese bureaucratic expertise enabled the Mongols to organize an efficient intelligence gathering i.e., spy system and to collate and analyse the information effectively. Also Chinese technicians provided the support and expertise in siege craft, machines etc., for how to effectively and quickly storm cities and fortresses. In Europe this was especially useful in that compared to Chinese cities and fortresses European cities and fortresses were not very challenging to take. In effect Mongol war making was a combination of steppe nomad traditional war making and Chinese technical / bureaucratic expertise. The combination proved to be brutally formidable and something the Europeans of the day had no answer too.15

The usual figures given even now, in my opinion, greatly exaggerate the size of the Mongol armies. Confusing paper strength with actual strength for one thing. Given that the Mongol armies were heavily horsed and mobile it is very unlikely that they would number over 100,000 for the invasion of Europe, even 50,000 is likely too large. Interestingly the Mongol armies invading China had large infantry units. Given that each fighting man would have at least 4 horses, (some accounts say 16) and that support forces would have at least 50% of the number of horses of the fighting men. That would mean an army of 50,000 men would have a minimum of 300,000 horses, to say nothing of mules donkeys etc. Given also that all cavalry armies are almost always much smaller than largely infantry armies, (because of the extra logistic support all those horses require), it is hard to believe that the Mongol armies invading Europe were very large.16

One of the half truths that is popular today is the idea of a “Western Way of Warfare”.17 The idea is that there is an especially different “Western" way of warfare that is more deadly and formidable than other ways. In other words another way of flattering “Westerners” i.e., Europeans on their supposed superiority. I rather think that an unbiased look the history of warfare would call into question any notion that the “Western Way of Warfare” is in fact necessarily superior, assuming such a concept is in fact for real. It also feeds into the European notion of the “Oriental Horde” defeated by the small European army in a decisive battle that saves the “West” from the horrors of a decadent Asia.

It did not happen in this case then backwater Europe was saved by a mere fluke, a stroke of luck that the Europeans did nothing to take advantage of. Only later developments in central Asia and China prevented the renewal of the conquest of Europe. There is no decisive battle to write up in collections of decisive battles. The battles of Liegnitz and Sajo would likely have marked the decisive battles in the conquest of Europe except for a fluke event. Even so it is passing ironic that Subotai who organized one of the great campaigns of military history was the one responsible for calling it off. It appears that he expected to come back to it in a couple of years. Fortunately for Europe he never came back and Liegnitz and Sajo are simply decisive battles that might have been.

Sometimes small things have huge effects and in this case Ogatai’s decision to drink a few extra cups of wine may be one of the most important decisions in the last thousand years.

1. See Keegan, John, The Face of Battle, Penguin Books, London, 1976, pp. 13-77, for a critique of the concept of the decisive battle.

2. See Creasy, Sir Edward S., The Fifteen Decisive Battles, London, 1908, and Fuller, J. F. C., A Military History of the Western World, v. 1-3, Da Capo Press, New York, 1954, 1955, 1956, Dupuy, R. Ernest, & Dupuy, Trevor N., The Encyclopedia of Military History, Revised Edition, Harper & Row Pub., New York, 1977, for many examples of this sort of thinking.

3. IBID, Fuller.

4. Fuller does this a lot and so do Dupuy & Dupuy.

5. Footnote 1.

6. See Creasy for example.

7. The idea of a “Western Way of War”, is from Hanson, V., The Western Way of War, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1989. Although the book is excellent he does not in any sense prove his idea that the “Western Way of War” is superior or that it is unique to the “West”. John Keegan in his A History of Warfare, Vintage, New York, 1993, uses the idea with great care and sense.

8. Dupuy, pp. 338-339, Prawdin, Michael, The Mongol Empire, 2nd Edition, The Free Press, New York, 1961, pp. 210-220, Mote, F. W., Imperial China 900-1800, Harvard University Press, Harvard CONN, 1999, pp. 432-433, Turnbull, Steven, Genghis Khan and the Mongol Conquests, Osprey Pub., 2003, pp. 74-75, Buell, Paul E., Historical Dictionary of the Mongol World Empire, The Scarecrow Press Inc., Oxford, 2003, pp. 35-36, 255-258, Shpakovsky, V., & Nicolle, D., Kalka River 1223, Osprey Pub., 2001, pp. 50-82.

9. Prawdin, pp. 250-252, Dupuy, 347, Mote, 435-436, Buell, pp. 45-46, 233-234, Turnbull, pp. 44-48.

10. Prawdin, 252-269, Dupuy, 347-350, Mote, 435-436, Buell, pp. 46-47, 186-187, 235, 257-258, Turnbull, pp. 48-54, 75.

11. Ögedei Khan, from Wikipedia, Here, Dupuy, p. 350, Prawdin, p. 269, Mote, p. 436, Turnbull, p. 55, Dawson, Raymond, Imperial China, Penguin Books, London, 1972, p. 215. There were rumours that Ogatai was poisoned. These rumours are almost certainly not true.

12. Dupuy, quoting the law p. 350.

13. Dupuy, p. 350.

14. Mote, 444-460, Turnbull, pp. 55-56, 60-61, Dawson, pp. 212-221.

15. Dupuy, 340-345, Keegan 1993, 200-207, Dawson, 204-212, Shpakovsky, pp. 23-35, Turnbull, pp. 17-18, Buell, pp. 112-113.

16. Mote, pp. 427-428, Turnbull, p. 18, Buell, pp. 109-110. Dupuy and Dupuy are especially guilty in this respect giving very exaggerated figures for both the Mongol armies and the European armies opposing them, see pp. 347-350.

17. See Hanson Footnote 7.

Pierre Cloutier

Monday, November 30, 2009

The history of China is fascinating one and full of strange and wonderful events. One of the strangest and most extraordinary is the story of the Empress Wu Zetian.

This story is not well known to the non-Chinese but it does have massive doses of sex and violence to say nothing of carpet chewing over the top plot and intrigue.

This story is about how not only did the Empress Wu Zetian became the de-facto ruler of China but decided to go for it all and make herself Emperor. To became the only women in Chinese history to make herself not just ruler of China but the official ruler of China.1

The Empress Wu Zetian or to give her name Wu Chao, had started out as a concubine in the harem of the second Tang Emperor and had gone on from that to make herself all powerful during the reign of the third Tang Emperor.

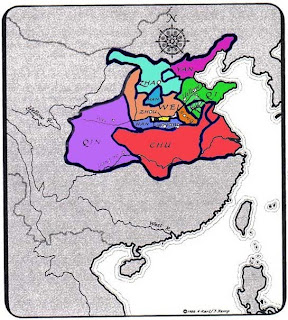

To give some background. In the late 6th century C.E., the Sui dynasty had reunified China after almost 400 years of division, civil war and chaos since the fall of the Han dynasty, (c. 220 C.E.)2

The second Sui Emperor, Yang Ti, had dissipated the good will created by his father Wen Ti with a series of brutal policies and wasteful extravagance.3 The result was widespread revolt. Eventually Yang Ti was overthrown by a coup and strangled.4

During this chaos Gaozu took the Chinese capital of Chang-an and established the Tang dynasty by proclaiming himself Emperor in 618 C.E. During all of this he was aided and apparently heavily prodded by his able and ruthless son Taizong. By 626 C.E. China was reunified.5

Taizong in a series of rather ruthless intrigues eliminated his two older brothers and then compelled his father Gaozu to abdicate in 626 C.E. Gaozu lived until 635 C.E. in retirement.

Taizong is considered to be one of the greatest if not the greatest of Chinese Emperors and his reign became a model for how a Chinese Emperor should rule.6

However despite the glory of his reign it was marred by the continual violent intrigues within the court including the usual interminable struggle of the succession.

During all of this Wu Chao entered the Imperial court as a concubine.

Wu Chao was born in the year 625 C.E., and we have the usual stories that were popular among Chinese writers and historians concerning alleged portents that indicated that she would rule. It is rather annoying that historians who should know better take these rather amusing stories concocted after the fact with any sort of seriousness. They are simply not to be taken as anything other than post-hoc concoctions.7

One story has it that a Chinese “face” reader, after examining her face and the way she walked when he examined her at the age of c. 3 years concluded that if she was a girl she would become Emperor of China. Given Chinese and official Confucian attitudes towards women this story can be dismissed as a post-hoc fantasy.8

Other stories like the alleged fact that she liked to wear boy’s clothes as a child and like to explore and go about un-supervised unlike the typical lives of aristocratic girls of the time are more substantial than fantasies concerning alleged prognostications of her future power. This is so because such reports make sense given the very forceful and independent personality Wu Chao would show as Empress. So it would not be a surprise if she exhibited such characteristics as a child.9

Wu Chao’s family, the Wu, although of impeccable aristocratic background and supporters of the Tang dynasty was not a particularity important family and they were to be of little importance or use to Wu Chao in her rise to power. In fact unlike virtually every other Empress who rose to power in Chinese history it was not Wu Chao’s family that was responsible for her rise to power but Wu Chao who was responsible for her families rise to power.10

At the age of 13 in 638 C. E., Wu Chao was selected to be a concubine for the harem of Taizong. She was selected mainly because of her beauty.

We have little idea of what the next decade was like for Wu Chao. It appears that she stayed a minor concubine and further she had no children which severely limited any chance that she could rise in the palace hierarchy. Again several stories are told about Wu Zetain during this time period but they are not really all that plausible but they do give a good idea of what people thought were her chief character traits. Included in these stories is the following which the Empress Wu Zetian allegedly told in later life.

Emperor Taizong had a horse with the name "Lion Stallion," and it was so large and strong that no one could get on its back. I was a lady in waiting attending Emperor Taizong, and I suggested to him, "I only need three things to subordinate it: an iron whip, an iron hammer, and a sharp dagger. I will whip it with the iron whip. If it does not submit, I will hammer its head with the iron hammer. If it still does not submit, I will cut its throat with the dagger." Emperor Taizong praised my bravery. Do you really believe that you are qualified to dirty my dagger.11Apparently the Emperor Taizong was a little taken aback by Wu Chao’s rather formidable nature and did not advance her in the palace hierarchy.

In the year 649 C.E., the Emperor Taizong died to be succeeded by his son Emperor Gaozong; considered a weak and rather spineless figure, who reigned until 683 C.E.

Now at the time the custom of the court was that the concubines of the old Emperor upon the Emperor’s death, who had not had children, would retire to live in Buddhist Nunneries.

Thus it appears that at the age of 24 the Wu Chao would live the rest of her life as a Buddhist Nun. That did not happen for the following reasons.12

It appears that Wu Chao had made the acquaintance of Gaozong before Taizong’s death. The story was that Wu Chao seduced him before his father’s death. Since sleeping with the Emperor’s wives and concubines was considered treason and could even get a Emperor’s son killed or disinherited this idea is at least doubtful. Further it fits the rather dull stereotype of the sexually insatiable strong women who gets ahead using sex, that is a common cliché in Chinese historical writing.13

It does appear to be the case though that Wu Chao and Gaozong knew each other and that Gaozong had a certain fondness for her even before his father’s death.

According to the writers what happened was that Gaozong’s Empress named Wang and the Emperor’s favourite concubine Hsiao were engaged in a serious power struggle and the Empress, who was childless, endeavoured to bring Wu Chao back as a rival to keep Hsiao at bay in the interminable game of palace politics.

However what seems to have actually happened is that Wu Chao kept in touch with both Emperor Gaozong and Empress Wang in an effort to cut short her retirement. Wu Chao apparently promised undying gratitude and loyalty to the Empress Wang if she arranged for her to be brought back or at least did not oppose it.

During her exile Wu Chao composed the following poem addressed to Gaozong:

Watching red turn to green, my thoughts are tangled and scattered,Whatever the actual details of the matter in the year 650 Emperor Gaozong visited the Convent Wu Chao was living at and brought her back to court as one of his concubines. An act which was considered incredibly scandalous, especially since sleeping with your father’s concubines was considered a form of incest.15

I am dishevelled and torn from my longing for you, my lord.

If you fail to believe that lately I have shed tears constantly,

Open my chest and look for the skirt of pomegranate-red.14

Now of course Chinese historians attribute boundless ambition to Wu Chao from the beginning. I rather suspect that what actually was going on was the simple desire of a young women to escape confinement and return to the excitement of court.

What happened next is probably what was decisive. Wu Chao found out that both the Empress Wang and Hsiao, Emperor Gaozong’s favourite concubine were very unpopular at court, further she found out that Gaozong needed help in actually running the Empire. Both those discoveries were decisive in the Empress Wu’s ascent to power.16

Gaozong has had, to put it mildly, an enormous amount of bad press for allegedly being a weakling, a sexual pervert, a stupid man and a complete tool in the hands of Wu Chao. There is room to question that verdict. It appears likely that he was actually fairly intelligent and further that he never became a complete tool in hands of Wu Chao. However it does appear that he was physically a very sickly man subject to blinding headaches and general serious physical weakness, and has he got older he got weaker. It also appears that unlike a lot of weak people he had enough sense to realize that he needed help. In other words Gaozong was simply not up to the demands of running the Empire. It appears that his wife Wang and his other concubines were of absolutely no help to him in terms of helping him rule. They seemed to be more interested in getting riches and favours for themselves and their families than helping him. Wu Chao almost from the moment she was released from confinement was involved in helping him administer and acting to as an advisor to him; that rather than her alleged submission to Gaozong’s supposed sexual perversions was the likely source of her rise to power. Also despite what the historians said later it should be considered at least plausible that Wu Chao, although ruthlessly ambitious genuinely loved her husband.

Wu Chao also shortly began to have children which made the position of the Empress Wang more precarious.

Within a few years Wu Chao began to intrigue against the Empress Wang and the concubine Hsiao. It was no contest. Not only were they both unpopular, they simply were not as bright or good at the game of court politics. Unlike Empress Wang and Hsiao, who dissipated it, Wu Chao used the favours and wealth she received to set up a network of spies in the palace along with a network of people who were loyal to her. The fact that, at least, face to face she exercised tact and modesty also helped. Further Wu Chao deliberately sought out and helped those that the Empress Wang and her family had offended. A high degree of ruthlessness also helped.

In one particularity grotesque incident after Wu Chao gave birth to a daughter. The Empress Wang visited the child. Shortly afterwards the child died. Wu Chao blamed the Empress. Some later Chinese Historians claimed that Wu Chao strangled the child in order to blame the Empress Wang for the death. Aside from indicating the degree of animosity against the Wu Chao by later historians the charge can be dismissed, given that it was a age of very high infant mortality. Although Wu Chao’s willingness to so accuse Empress Wang is a rather telling indication of ruthlessness.17

Wu Chao then introduced Gaozong to her sister, Ho-Lan further cementing her hold over him; given that Gaozong and Ho-Lan soon became lovers.

Wu Chao then began a series of rather complicated intrigues aimed at replacing Empress Wang with herself as Empress. As part of the game of court politics Empress Wang’s mother was banned from court for allegedly practicing sorcery against Wu Chao. Many of Gaozong’s advisors were adamantly opposed to making Wu Chao Empress and opposed the move. Wu Chao was livid, for by this time she had taken to listening to the Emperor’s advisers advising the Emperor from behind a screen. Given that this was very unusual this indicates the role that Wu Chao had already taken as an advisor to the Emperor.

It took a while but gradually Wu Chao got rid of the advisers who opposed her elevation to becoming Empress, by championing a court faction that supported her as a way of getting rid of the old guard and coming to power.

Eventually Empress Wang and Hsiao were accused of plotting to poison the Emperor and disposed and replaced by Wu Chao in 655 C.E. Not long after they were killed by having their hands and feet cut off and being left to bleed to death. The new Empress Wu Zetian punished those who had opposed her elevation to power and rewarded her allies. Her son Li Hung was made crown prince replacing Li Chung the Empress Wang’s adopted son who was not long for this world.18

The Empress Wang took her fall and death rather stoically. The concubine Hsiao was a lot less resigned. Hsiao allegedly said:

‘Wu is a deceitful fox, who had sealed my fate,’ she said. ‘I pray that in all my future lives I will come back as a cat, and she is a mouse. Then in each life I will tear her throat out’19The Empress Wu is said to have removed all the cats from the various Imperial palaces in response.

The next few years were an interminable wrangle of petty palace intrigues and vendettas as the Empress Wu Zetian consolidated her position with considerable bloodshed and ruthlessness, but on a more constructive note showed a extraordinary talent for selecting able men to help rule the empire. Among those eliminated were certain relatives of the Empress Wang who had blocked Wu Zetain’s ascent and who she considered threats to her position.

Two things marked the great turning point by which Wu Zetian became if the not the sole ruler of the Empire the main ruler with her husband Gaozong giving up most authority to her although he did not make her regent. In late 660 C.E. Gaozong got very seriously ill and the Empress Wu Zetian took over the day to day administration of the Empire. She very quickly proved to be remarkably able and had the stamina for the tedious time consuming work of day to day administration. Although the Emperor eventually recovered Wu Zetain remained active in the day to day administration of the empire from then on. It appears that from then on even when the Emperor was in good health most of the day to day administrative work remained in the hands of the Empress Wu Zetain.

A few years after this, in 663 C.E., a final attempt was made to dispose Wu Zetain. It appears that Wu Zetain had employed a certain Taoist priest who was alleged to have engaged in sorcery. Certain of the Emperor Gaozong’s advisors used this to get from him a degree ousting Wu Zetain as Empress. The fact that Wu Zetain had also been acting arrogantly had also enraged the Emperor. Unfortunately for the plotters the Empress had spies all over the palace who reported this too her. Wu Zetain rather than hide or beg went and confronted her husband Gaozong. The historians claim that Gaozong just gave in fearing her anger. Rather doubtful. It appears that Wu Zetain got rid of the Taoist priest and started acting more modestly and less arrogantly. No doubt she reminded her husband of her considerable political and administrative skills and her basic loyalty to him. The advisors and officials who advised Gaozong on this course of action were arrested and imprisoned. Wu Zetain was now securely position as if not ruler of China as at least co-ruler of China.20

The dynastic history records as follows concerning the aftermath of this final attempt to oust Wu Zetain:

From this event, whenever the Emperor attended to business, the Empress hung a curtain and listened from behind it. There was no matter of government, great or small, she did not hear. The whole sovereign power of the Empire passed into her hands. Life and death, reward or punishment were hers to decide. The Son of Heaven sat on the throne and folded his hands, that is all. In court and in the country, they were called the Two Sages.21At another time I will look at the process by which Wu Zetain made herself official ruler of China.

1. Dawson, Raymond, Imperial China, Penguin Books, London, 1972, pp. 88-89, Benn, Charles, China’s Golden Age, Oxford University Press, 2002, pp. 4-5.

2. IBID, pp. 52-65.

3. IBID, Benn, p. 1, Wen Ti reigned 581-604 C.E. Yang Ti 604-618 C.E. Executions, the brutal building of the Grand canal and incredible extravagance in the midst of famine and natural disaster were the back ground to revolt along with disastrous invasions of Korea.

4. Dawson, p. 64.

5. Yes that is where the orange drink got its name.

6. See Dawson, pp. 69-81, Fitzgerald, C. P., Son of Heaven, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1933, for a biography of this extraordinary man. Benn gives an excellent overview of what life was like during the Tang dynasty.

7. Both Fitzgerald, C. P., The Empress Wu, Second Edition, Cresset Press, London, 1968, and Cawthorne, Nigel, Daughter of Heaven, One World Pub., Oxford, 2007, take these stories too seriously.

8. See Cawthorne, pp. 18-19, Fitzgerald, 1968, repeats the story in his prologue.

9. IBID, pp. 16-18. See also Fitzgerald, 1968, pp. 1-15.

10. Both Cawthorne and Fitzgerald both make this quite clear. See also Dawson pp. 81-85.

11. Wikipedia, Wu Zetian Here. Quoting a Chinese Historian.

12. Cawthorne, pp. 66-71, Dawson, pp. 81-82.

13. IBID, pp. 44-61, 66-67, 70-73. See also Fitzgerald 1968.

14. Cawthrone p. 69.

15. IBID, 70-71, See also Fitzgerald, 1968.

16. IBID, p. 73. See also Dawson, pp. 81-83.

17. IBID, p. 74, Dawson, p. 82, Fitzgerald , 1968 is especially emphatic that it is unlikely that the Empress Wu murdered the child.

18. IBID, pp 76-78, 83-84, Dawson, pp. 81-83. See also Fitzgerald 1968.

19. IBID, p. 83. Quoting a Chinese Historian.

20. IBID, pp. 91-92, 94-95. See also Fitzgerald, 1968.

21. Cawthrone, p. 96. Quoting the Dynastic History. Part of quote also appears in Dawson, p. 82 and Fitzgerald, 1968.

Pierre Cloutier

Friday, November 06, 2009

Those however were just the two most successful schools of philosophy that arose during this time period. Another school that flourished during this time period was founded by a man called Mozi, (also Mo Tzu). He was born c. 470 B.C.E. and died c. 390 B.C.E. Mozi was born an artisan although he apparently served for a time as a Minister in the Court of the state of Song. He apparently was an extremely capable carpenter and loved to build mechanical devices, such as purely amusing gadgets and siege devices. He set up a school were he taught disciples things which he thought would aid them in becoming government officials. Mozi was also apparently much sought for his advice regarding fortifications and siege craft.2

We know that Mozi was greatly admired during his life time for his concern for people’s well being and for his earnest attempts to make peace between the warring Chinese states of his time. His belief in peace and his attempts to procure for others its blessings, as led many to call him a pacifist. This is an error as indicated by his teaching the arts of fortification and defence. Mozi had no trouble with the idea of defending oneself even with violence, and thought that refusing to defend oneself from unjust attack was simply foolish. Mozi’s philosophy was in many ways highly pragmatic. Despite that some of the ideas he had seemed very idealistic he always tried to ground them firmly in reality and utilitarian usefulness.

For example Mozi’s definition of the superior man is:

The way of the superior man makes the individual incorruptible in poverty and righteous when wealthy; it makes him love the living and mourn the dead. These four qualities of conduct cannot be hypocritically embodied in one's personality. There is nothing in his mind that goes beyond love; there is nothing in his behaviour that goes beyond respectfulness, and there is nothing from his mouth that goes beyond gentility. When one pursues such a way until it pervades his four limbs and permeates his flesh and skin, and until he becomes white-haired and bald-headed without ceasing, one is truly a sage.3

Mozi is best known for his belief in Universal Love. For Example:

Suppose everybody in the world loves universally, loving others as one's self. Will there yet be any unfilial individual? When every one regards his father, elder brother, and emperor as himself, whereto can he direct any unfilial feeling? Will there still be any unaffectionate individual? When every one regards his younger brother, son, and minister as himself, whereto can he direct any disaffection? Therefore there will not be any unfilial feeling or disaffection. Will there then be any thieves and robbers? When every one regards other families as his own family, who will steal? When every one regards other persons as his own person, who will rob? Therefore there will not be any thieves or robbers. Will there be mutual disturbance among the houses of the ministers and invasion among the states of the feudal lords? When every one regards the houses of others as one's own, who will be disturbing? When every one regards the states of others as one's own, who will invade? Therefore there will be neither disturbances among the houses of the ministers nor invasion among the states of the feudal lords.4

So, when there is universal love in the world it will be orderly, and when there is mutual hate in the world it will be disorderly.5

Now that there is disapproval, how can we have the condition altered? Mozi said it is to be altered by the way of universal love and mutual aid. But what is the way of universal love and mutual aid? Mozi said: It is to regard the state of others as one's own, the houses of others as one's own, the persons of others as one's self. When feudal lords love one another there will be no more war; when heads of houses love one another there will be no more mutual usurpation; when individuals love one another there will be no more mutual injury.6

Whoever loves others is loved by others; whoever benefits others is benefited by others; whoever hates others is hated by others; whoever injures others is injured by others.7

Thus the old and those who have neither wife nor children will have the support and supply to spend their old age with, and the young and weak and orphans will have the care and admonition to grow up in. When universal love is adopted as the standard, then such are the consequent benefits. It is incomprehensible, then, why people should object to universal love when they hear it.8

Yet the objection is not all exhausted. It is asked, "It may be a good thing, but can it be of any use?" Mozi replied: If it were not useful then even I would disapprove of it.9

…universal love is really the way of the sage-kings. It is what gives peace to the rulers and sustenance to the people. The gentleman would do well to understand and practise universal love; then he would be gracious as a ruler, loyal as a minister, affectionate as a father, filial as a son, courteous as an elder brother, and respectful as a younger brother. So, if the gentleman desires to be a gracious ruler, a loyal minister, an affectionate father, a filial son, a courteous elder brother, and a respectful younger brother, universal love must be practised. It is the way of the sage-kings and the great blessing of the people.10

…when it comes to the great attack of states, they do not know that they should condemn it. On the contrary, they applaud it, calling it righteous. Can this be said to be knowing the difference between righteousness and unrighteousness?11

Further offensive war is not pragmatic:

But men of Heaven are murdered, spirits are deprived of their sacrifices, the earlier kings are neglected, the multitude are tortured and the people are scattered; it is then not a blessing to the spirits in the middle. Is it intended to bless the people? But the blessing of the people by killing them off must be very meagre. And when we calculate the expense, which is the root of the calamities to living, we find the property of innumerable people is exhausted. It is, then, not a blessing to the people below either.13

Mozi said: Just so that on the side it can keep off the wind and the cold, on top it can keep off the snow, frost, rain, and dew, within it is clean enough for sacrificial purposes, and that the partition in the palace is high enough to separate the men from the women. What causes extra expenditure but does not add any benefit to the people, the sage-kings will not undertake.14

Again Mozi’s philosophy is pragmatic, commonsensical and geared to minimizing conflict and disharmony by what amounts to pragmatic self interest.

Mozi attacks the idea that elaborate funerals and extended mourning are good and virtuous He says:

…if in adopting the doctrine and practising the principle, elaborate funeral and extended mourning really cannot enrich the poor, increase the few, remove danger and regulate disorder, they are not magnanimous, righteous, and the duty of the filial son. Those who are to give counsel cannot but discourage it. Now, (we have seen) that to seek to enrich a country thereby brings about poverty; to seek to increase the people thereby results in a decrease; and to seek to regulate government thereby begets disorder. To seek to prevent the large states from attacking the small ones by this way is impossible on the one hand, and, on the other, to seek to procure blessing from God and the spirits through it only brings calamity. When we look up and examine the ways of Yao, Shun, Yu, Tang, Wen, and Wu, we find it is diametrically opposed to (these). But when we look down and examine the regimes of Jie, Zhou, You, and Li, we find it agrees with these like two parts of a tally. So, judging from these, elaborate funeral and extended mourning are not the way of the sage-kings.15

Mozi believed that Heaven consecrates and determines the boundaries of a proper human life. And that:

…this does not exhaust my reasons whereby I know Heaven loves man dearly. It is said the murder of an innocent individual will call down a calamity. Who is the innocent? Man is. From whom is the visitation? From Heaven. If Heaven does not love the people dearly, why should Heaven send down a visitation upon the man who murders the innocent? Thus I know Heaven loves man dearly.16

Be sure to do what Heaven desires and avoid what Heaven abominates. Now, what does Heaven desire and what does Heaven abominate? Heaven desires righteousness and abominates unrighteousness. How do we know this? Because righteousness is the standard. How do we know righteousness is the standard? Because with righteousness the world will be orderly; without it the world will be disorderly. So, I know righteousness is the standard.17

Further in his pragmatism Mozi goes very far indeed:

The policy of the magnanimous will pursue what procures benefits of the world and destroy its calamities. If anything, when established as a law, is beneficial to the people it will be done; if not, it will not be done. Moreover, the magnanimous in their care for the world do not think of doing those things which delight the eyes, please the ears, gratify the taste, and ease the body. When these deprive the people of their means of clothing and food, the magnanimous would not undertake them. So the reason why Mozi condemns music is not because that the sounds of the big bell, the sounding drum, the qin and the se and the yu and the sheng are not pleasant, that the carvings and ornaments are not delightful, that the fried and the broiled meats of the grass-fed and the grain-fed animals are not gratifying, or that the high towers, grand harbours, and quiet villas are not comfortable. Although the body knows they are comfortable, the mouth knows they are gratifying, the eyes know they are delightful, and the ears know they are pleasing, yet they are found not to be in accordance with the deeds of the sage-kings of antiquity and not to contribute to the benefits of the people at present. And so Mozi proclaims: To have music is wrong.18

Mozi also accepted the idea that the spirits of the dead influenced the lives of the living, but he firmly rejected any doctrine of Fatalism because of its consequences:

If the doctrine of the fatalist were put to practice, the superiors would not attend to government and the subordinates would not attend to work. If the superior does not attend to government, jurisdiction and administration will be in chaos. If the subordinates do not attend to work, wealth will not be sufficient. Then, there will not be wherewith to provide for the cakes and wine to worship and do sacrifice to God, ghosts and spirits above, and there will not be wherewith to tranquillize the virtuous of the world below; there will not be wherewith to entertain the noble guests from without, and there will not be wherewith to feed the hungry, clothe the cold, and care for the aged and weak within. Therefore fatalism is not helpful to Heaven above, nor to the spirits in the middle sphere, nor to man below. The eccentric belief in this doctrine is responsible for pernicious ideas and is the way of the wicked.19

Mozi rejected Confucianism mainly on grounds of it upholding contradictory doctrines and practices that are not conducive to proper conduct along with being absurd and tending towards extravagance and waste. For example:

Mozi said concerning what is the most valuable thing in existence:Again, the Confucianist says: "The superior man conforms to the old but does not make innovations." We answer him: In antiquity Yi invented the bow, Yu invented armour, Xi Zhong invented vehicles, and Qiao Cui invented boats. Would he say, the tanners, armourers, and carpenters of to-day are all superior men, whereas Yi, Yu, Xi Zhong, and Qiao Cui were all ordinary men? Moreover, some of those whom he follows must have been inventors. Then his instructions are after all the ways of the ordinary men.20

Hence we say, of the multitude of things none is more valuable than righteousness.21

Mozi when he was discovered by Western experts on China in the 19th century was thought to be a precursor of Jesus. This was largely because of his passages condemning war and expressing the desirability of Universal Love. Yet in some respects the similarity is just a similarity. For example Mozi, ever the pragmatist, did not condemn all war but only offensive war. Of course he realized if there were few offensive wars there would also be few defensive wars; in fact few wars of any kind. He himself was an expert on fortifications and defence and advised the rulers of his day on those things. Further he believed in the right to self defence. Also his doctrine of Universal Love was pragmatic and prudential. He worked out that since people benefited from it in terms of prosperity and peace then it was good he explicitly said if people did not benefit than it was of no use.

Mozi’s attacks on then traditional morality regarding both filial pity, treatment of the dead and music are in some respects so practical and pragmatic has to have a decidedly inhuman aspect. Sometimes moderation is in itself immoderate and extreme.

In the end the Chinese although largely ignoring him for over 2000 years did carefully preserve his writings and although perhaps if we heed his message that Universal Love is not simply an airy abstraction but a concrete prudential, pragmatic and in effect selfish practical attitude we might get a little closer to getting along with each other.

In closing I give an example of Mozi the practical man of action

Gong Shuzi confessed to Mozi: "Before I saw you, I wished to take Song. Since I have seen you, even if Song were offered me I would not take it if it is unrighteous." Mozi said: Before you saw me you wished to take Song. Since you have seen me even if Song were offered to you, you would not take it if it unrighteous. This means I have given you Song. If you engage yourself in doing righteousness, I shall yet give you the whole world.23Not many men can claim to have saved who knows how many of his fellow human beings from pain, suffering and death. That is probably Mozi’s greatest monument.

2. Mozi, Wikipedia Here

3. Mozi, Mozi, Book I, Self Cultivation s. 3, Chinese Text Project at Here.

4. Mozi, Book 4, Universal Love I s. 4.

5. IBID, s.5.

6. IBID, Book 4, Universal Love II, s.3.

7. IBID. s. 4.

8. IBID, Book 4, Universal Love III, s. 3.

9. IBID, s. 4.

10. IBID, s.12.

11. IBID, Book 5, Condemnation of Offensive War I, s. 1.

12. IBID, s.2.

13. IBID, Condemnation of Offensive War III, s. 2.

14. IBID, Book 6, Economy of Expenditures II, s. 6.

15. IBID, Simplicity in Funerals III, s. 11.

16. IBID, Book 7, Will of Heaven II, s. 7.

17. IBID, Will of Heaven III, s. 2.

18. IBID, Book 8, Condemnation of Music I, s. 1.

19. IBID, Book 9, Anti-Fatalism I, s. 6.

20. IBID, Anti-Confucian II, s. 5.

21, IBID, Book 12, Esteem for Righteousness, s. 1.

22. IBID, Books 14 & 15.

23. IBID, Book 13, Lu’s Question, s. 22.

Pierre Cloutier

Sunday, August 09, 2009

Menzies' Voyages

Menzies' VoyagesA few years ago Gavin Menzies' book 1421 was published1 amidst a blaze of publicity and controversy, rather than discuss the “merits”, zero in my opinion, of Menzies’ worthless piece of pseudo-scientific garbage.2 I will briefly discuss what we know about how this piece of “scholarship” was manufactured.

I used the word manufactured quite deliberately above, because yes indeed this book was not “researched” or “written” it was manufactured quite deliberately and coldly to make the publisher, and yes the writer, boodles of cash, with of course absolutely no qualms, ethical, moral or simply prudent whatsoever.

Let us go through the steps by which this work of no value was manufactured from the bowels of a shameless publisher.

It all stated when Menzies and his wife traveled to China for their silver wedding anniversary. While visiting the Forbidden City in Beijing Menzies noticed that the dates of all sorts of buildings etc., was the date 1421. Which was the year the capital was moved from Nanjing to Beijing during the reign of the Yongle Emperor.4

Menzies decided to write a book about the year 1421 in China and the rest of the world. The result was a huge book of 1,500 pages. By this time Menzies had acquired an agent who told him that the manuscript has written was un-sellable. However his agent did have a few suggestions…5

In a very small part of the manuscript Menzies had a far out speculation about Admiral Zheng He’s subordinates exploring the world c. 1421. The agent suggested Menzies dump the rest of the book and expand that section massively.

And I then said to him, ‘Look, let's forget what was happening in France and Germany and Britain in the 15th century, let's just look at this one episode and let's make the whole book the story of how China discovered America.’6

Further it was decided to get the media involved in publicizing Menzies’ idea. The agent even decided to rewrite some of the chapters. So a public relations company was contacted and got involved and soon a story was published in the Daily Telegraph and further Menzies gave a talk at the Royal Geographical Society, (they will rent to anyone it seems). Soon major publishers were interested.7

The publisher finally selected was Transworld and one of its subsidiaries Bantam Books. They offered 500,000 pounds for the world rights to 1421. A problem was that despite the extensive expansion of that short section by Menzies the book was still only 190 pages and apparently was badly written and confusing to look at. So Bantam decided to “improve” the manuscript. Supposedly Menzies was told that he could not write.8

It was dry as dust. And Transworld said, "Well" - after they bought it, they said, "You know, this is a great book, potentially, but nobody's going to read it. You know, if you want to get your story over, you've got make it readable, and you can't write, basically." I mean, in a sort of polite way.9

So they had a large staff of supposedly 130 people work on “improving” the book including a ghost writer by the name of Neil Hanson. All the research remained Menzies however and despite the large resources devoted to “improving” the book, zero effort seems to have gone into checking out the books claims.10

As one of the publishers said:

It's very hard to prove that something is or is not correct. I mean, we do have to rely on our authors - we - we simply don't have the time. I mean, we work full - flat out publishing the books, bringing them to press, marketing them, publicising them, selling them - we can't possibly go through all our books and check every single one of them out for factual accuracy.11

Where does one begin with such bold faced cheek! The fact is they devoted extensive resources to “improving” the book, including hiring a ghost writer, and then to marketing the book. It would not have been all the difficult to have the book checked out by a few experts in maritime and Chinese history or to have hired a fact checker to check out a few things.

The bottom line is that the publisher could not be bothered to do anything that might throw a monkey wrench into their desire to earn mega-profits from this piece of dribble.

One of the publishers did say:

What Gavin was claiming, was, of itself, a step away from orthodox history, and anything that says - that does - that is, can be, sensational, or certainly different. And we're always looking for things - as are lots of people - that really go up against conventional wisdom, and this is what I thought this book did.12

Roughly translated we saw this as a bit of sensationalistic clap-trap that would make us much boodle. Of course it was deliberately marked as sensationalistic and a “controversy” was manufactured out of whole cloth, by the publisher as a way of boosting sales of the book.13

Typical of the mindset of the publisher was the claim on the book that Menzies was born in China. He wasn’t; he was born in London.14

The book was published and quite predictably got a torrent of vicious reviews, but well over a million were sold, the book has been translated into many languages and will into the future make even more boodle for Menzies and his publishers.15

The result has been that Menzies is well known and is a sought after public speaker and his book and its equally worthless follow up 1434,16 are selling very well.

This book as been described as:

The most successful book of pseudohistory to appear since Ignatius Donnelly’s Atlantis: the Antidiluvian World over a hundred years earlier. The difference between the books is that when Donnelly wrote his research had some scientific and historical credibility based on the state of knowledge at the time. Menzies’ hypothesis and research has withered under the light of intelligent and informed criticism from the very beginning. His success has been the result of an extensive publicity and marketing campaign that ignored established scholarship and expert opinion in favour of sensationalistic and unwarranted speculation at every step of the way.17

It is clear that the publisher did not and does not care about the truth of Menzies absurd ideas, but cares very much about making acres of cash. By outrageous manipulation and yes “brazen effrontery” they have done precisely that.

1. Menzies, Gavin, 1421, Harper Perennial, New York, 2004.

2. For some critical reviews of Menzies see Findlay, Robert, How Not to (Re)Write World History, Journal of World History, v. 15. no. 2, June 2004, at Here, Hartz, Bill, Gavin’s Fantasy Land, at In the Hall of Maat, at Here,Dutch, Steven, 1421, at Steve Dutch Home Page, Here.,See also this website with lots of articles: The ‘1421’ Myth Exposed, at Here. The above is just some of the critical analysis on the web.

4. Fritze, Ronald H., Invented Knowledge, Reaktion Books, London, 2009, p. 99.

5. IBID. pp. 99-100. The agent’s name is Luigi Bonomi. I hope he enjoyed the money from his pact with the devil. See also Four Corners, Junk History, Broadcast on July 31, 2006, Transcript at Here.

6. Junk History.

7. Fritze. p. 100. The public relations company was Midas Public Relations. See Junk History also.

8. IBID.

9. Junk History.

10. IBID., Fritze, p. 100.

11. Junk History.

12. IBID.

13. IBID. Fritze, pp. 101-102.

14. Junk History.

15. Fritze, pp. 101-102.

16. Menzies, Gavin, 1434, Harper Perennial, New York, 2009. This book seems to be as much a calculated effort to make moolah as 1421. See The ‘1421’ Myth Exposed, above for some well deserved tearing apart of this book.

17 Fritze, p. 103.

Pierre Cloutier