Heretic

Pharaoh

A

Note

|

| The Aton |

One of the most controversial historical figures is that of the Pharaoh Akhenaten, a Pharaoh of the 18th dynasty who reigned c. 1353-1336 B.C.E.1 The reasons for the controversy are rather obvious, the Pharaoh’s attempted religious changes and to put it bluntly the rather grotesque physique indicated by the art work of his reign.

All of this has led to endless but ultimately quite fruitless and irrelevant speculation much of it totally absurd about Akhenaten’s motives. To say nothing of all sorts of idiotic speculation about the psychology of the Pharaoh.2

The fact is all we can do is make educated

guesses into why Akhenaten did what he did. Sadly the official records of his

reign are not terribly helpful in trying to figure out the motive and purposes

of his religious changes.3

It is of important to record that

although Akhenaten has earned a lot of kudos for his advanced religious views

he has also gotten a great amount of what can only be termed abuse that depends

more on personal dislike for the image of Akhenaton created in the mind of the

writer than on any actual documented behavior of Akhenaten4

In this posting I will treat just two aspects

of the reign of Akhenaten. The first is the question of why Akhenaten had

himself depicted in such a strange manner. Certainly it was strange in

comparison with the way Pharaoh’s usually were in Egyptian art. The second will

be a speculation about one of the motives for the religious revolution

attempted during his reign.

One of the most extraordinary features

of ancient Egyptian art is its startling consistency over time. Most people

would have trouble distinguishing between Egyptian art of the 26th

century B.C.E., and Egyptian art erected by the Ptolemaic Pharaohs of the 1st

B.C.E. And one of the most “orthodox” conventions of ancient Egyptian art was

how the Pharaoh was depicted.

The following is a thoroughly

conventional picture of the Pharaoh Akhenaton from early in his reign.

The Pharaoh Akhenaten

Note the massive shoulders, slender

waist and strong legs. This Pharaoh is an impressive imposing figure. Of course

what the Pharaoh’s really looked like is quite another matter. It is obvious

that these images are political propaganda, iconography and are not meant to be

realistic.5

The Pharaoh Akhenaten

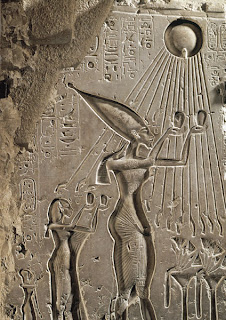

Now look at this depiction of the

Pharaoh Akhenaten. It certainly is far removed from that imposing figure. The

shoulders are small, the arms thin, the belly is not flat but protruding and potbellied.

The hips and upper legs massive in comparison to the upper body. The face instead of being compact and strong is elongated with large fleshy lips. The

expression not firm and commanding but dreamlike. In fact it looks like a

caricature.

The contrast with previous ways of

depicting the Pharaoh is very large.

So why did Akhenaten require this way of

depicting himself?

Several scholars have insisted that this

is what Akhenaten actually looked like. That Akhenaton had either Frohlich’s

syndrome or Marfan syndrome. The problem with this is that it assumes that

the representations are accurate representations of Akhenaten’s physical body.

The problems with that, aside from the

fact we don’t have Akhenaten’s body, are manifold.

First past representations of Pharaoh’s

were not physically accurate, so why assume this one is. Secondly the style was

used in the depictions of most everyone in art of the time period, especially

members of the Royal family.6

Secondly we have depictions of Akhenaten,

before he instigated his religious changes and they depict him as a

conventional Pharaoh.7

As for why Akhenaten was depicted in

this manner perhaps looking at religious iconography might be a more fruitful

source of explanation.

Well for example the elongated heads that

Akhenaten and his family were depicted with could represent the egg of

creation. The large thighs and hips could represent fertility. Similarly the

elongated face could possibly be a fertility symbol.8

It is important to remember that supreme

God according to Akhenaton was the Aton, who was the disk of the Sun. Akhenaton

perceived Aton as a source of fertility and abundance. The God was both

masculine and feminine in effect a bisexual, androgynous deity.9

In Akhenaten’s conception he was the Son

of the Aton which meant that he, like the Aton combined masculine and feminine

attributes. This characteristic would be shared by other members of the Royal

family in representation and of course it would be copied by others anxious for

royal favour.10

In Akhenaten’s new faith he and the

royal family worshiped the Aton and everyone else worshipped the Royal family

as children of the Aton. It appears to be the case that at the very least the

sculptures of Akhenaten and family greatly exaggerate certain features for iconographic

and religious propaganda reasons.11

A second issue is why did Akhenaten

embark on his attempted religious revolution. There were likely many reasons

but one likely reason will be outlined here.

It has been noted by many that Akhenaten

during his reign showed particular animosity against the cult of Ammon. Now Ammon

was more or less the patron God of the 18th dynasty and had been

elevated to supremacy among the Egyptian Gods. In fact under the name of a

composite deity Ammon-Ra he had even usurped the position of the Sun God Ra.12

The result of all this was that steadily

over the years the Priesthood and Temples of Ammon had acquired vast wealth and

estates throughout Egypt, further the Priesthood of Ammon had steadily acquired

more and more economic and political power.13

In theory the Pharaoh of Egypt was a God

and the power of Pharaoh was supposedly unlimited. Steadily over the years the

power of Pharaoh was being increasingly challenged by the various Priesthoods,

especially that of Ammon. Gradually the Pharaoh felt both power and wealth

slipping out of his hands and the Priesthood gradually drawing more wealth into

its hands and leaving the Pharaoh with less.14

Now Akhenaten probably knew that there

was a time when Ammon was a mere local deity in Thebes. Further Akhenaten

likely knew of a time when in the Egyptian Old Kingdom, when the ruling deity

was the Sun in the form of the God Ra. During this time the Priesthoods were

nowhere near as powerful or wealthy further they were clearly subordinate to

the Pharaoh.

It is usual to consider Akhenaten a

religious revolutionary. However in some important respects Akhenaten was in

fact conservative and trying to turn the clock back. By crushing the cult of Ammon

and creating a new cult centered around the Sun and the royal family he was

endeavoring to reassert Pharaonic power, by curbing the wealth and power of the

priesthoods, especially that of Ammon.15

Akhenaten likely saw the powerful

priesthoods as a threat to his power and one that needed to be cut back and

pharaonic power and wealth reasserted and the priesthoods once again be made

subservient to the Pharaoh. Taking back all the wealth heaped upon the

priesthoods especially that of Ammon also played a role.

It for example appears to be the case

that the army, which probably felt the priesthoods to be rival for power in the

state seems to have supported Akhenaten’s policies and was rewarded for its

support.16

Thus in many respects Akhenaten was

attempting a counter revolution. A counter revolution that ultimately failed.

Sometime later I may do another posting

about Akhenaten.

1.

Stannish, Steven M., New Evidence

for the Amarna Period, Phd., Dissertation, Miami University History

Department, Oxford Ohio, 2001, p. ii.

2. I will spare the reader a list of the

wild, bootless, effusions concerning Akhenaton’s psychology but one can start

the road to fantasy land with Freud, Sigmund, Moses and Monotheism, 1939 can be found at The Internet Archive Here.

3. Aldred, Cyril, Akhenaten King of Egypt, Thames and Hudson, London, 1991, pp.

237-248, Wilson, John A., The Culture of

Ancient Egypt, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1951, pp. 206-216,

Breasted, James

Henry, A History of Egypt, Bantam

Books, New York, 1905, pp. 297-318, Redford, Donald P., Akhenaten The Heretic King, Princeton University Press, Princeton

NJ, 1984 pp. 57-63.

4. See Redford above and Reeves,

Nicholas, Egypt’s False Prophet

Akhenaten, Thames and Hudson, London, 2001, for outstanding examples of

dislike.

5. Picture is from Aldred p. 90.

6. Ibid, pp. 231-236, Marfan Syndrome, Wikipedia Here, Akhenaten, Wikipedia Here, Tyldesley,

Joyce, Nefertiti, Penguin Books,

London, 1998, pp. 92-109, Kemp, Barry, The

City of Akhenaton and Nefertiti: Amarna and its People, Thames pp. 23-45.

7. Aldred, pp. 88-92.

8. Aldred, pp. 231-236, Tyldesley, pp.

92-109.

9. Aldred, pp. 237-248, Tyldesley, pp.

67-91, Reeves, pp. 140-147, Wilson, pp. 222-233, Redford, pp. 169-181.

10. IBID, Reeves, pp. 146-149, Kemp, pp.

231-263.

11. Tyldesley, pp. 91-109, Aldred, pp.

86-94, Wilson, pp. 223-224.

12. Reeves, pp. 154-155, Aldred, pp.

279-290, Wilson, pp. 221-222, 225.

13. Wilson, pp. 206-210, Redford, pp.

158-165, Reeves, pp. 43-46.

14. IBID, Redford, pp. 185-203.

15. IBID, and Footnote 13.

16. Footnote 14, Wilson, p. 231.

Pierre Cloutier

No comments:

Post a Comment